Common Ground

Van Jones could easily have been the Luke Skywalker of the resistance. His CNN comments on the night of the 2016 election, characterizing Trump’s victory as a “whitelash,” went viral. And he wasn’t exactly an unknown before that.

For many years he’s been one of the most highly respected progressive activists in the country, building institutions and leading campaigns around racial equity, criminal justice reform, and a Green New Deal (yes, he was on it before Ocasio-Cortez).

Eric L. Motley, former special assistant to George W. Bush and current Executive Vice President of the Aspen Institute, shares on the hard knocks and treasures of growing up in a largely poor African-American town during the height of the civil rights era in his memoir Madison Park: A Place of Hope. In the memoir, Motley chronicles his journey from a rural town founded by freed slaves in Alabama to navigating the political terrain of the White House. Motley recounts formative and disappointing experiences around the issue of race and highlights some of the small-town heroes that poured into his life as a child. The memoir provides a thoughtful reflection of how faith and radical love within a tight-knit community can significantly impact a person’s life.

Motley recently spoke with Sojourners about his story.

For decades, people have milked metaphors of baseball and religion beyond what they are worth. It’s not illegal, though there should probably be a special place in hell for those who claim to see the Trinity in baseball’s rule that three outs end an inning, or that the ballpark is a “cathedral.”

The truth is, we can go deeper.

WHAT IS OUR responsibility to expectant mothers, workers suffering from prolonged illness, or parents with children dealing with a significant sickness? Many Christians will assume the “our” in question refers to individual believers or the church as a community of believers. But what if the “our” refers to society as a whole? How is the question answered then?

This is more than an abstract question. Across the U.S.—at local, state, and federal levels—governments are debating policies that would expand paid sick leave. The issue itself isn’t complicated: Some workers have paid time off when they or a family member falls ill, while tens of millions of others—disproportionately low-wage workers—do not. The latter often face the difficult choice of struggling through shifts while sick or staying home and putting their livelihoods at risk.

The benefits of paid sick leave policies are well documented, with studies detailing the economic benefits paid sick leave provides by lowering employee turnover and training costs, reducing public-assistance spending, and improving productivity. “Working sick costs the national economy $160 billion annually in lost productivity,” according to the Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. Even greater gains can be realized when expanded family leave policies are included.

POLICE BRUTALITY, the Affordable Care Act, climate change: When people with differing convictions on issues such as these come together for conversation, some prefer to first set aside the issues and focus on building relationships, while others want disagreements front and center. In his book I Beg to Differ: Navigating Difficult Conversations With Truth and Love, Biola University communications professor Tim Muehlhoff says relationship and honesty are necessary for progress to be made.

“If every conversation we have with others is about the issues that divide us, the intensity will hurt the communication climate,” he writes.

For example, he offers the hypothetical story of an evangelical Christian who wants to share his faith with a Muslim co-worker. Over lunch, the colleagues take time to learn about each other’s differing religious convictions, but the conversation doesn’t invade their work relationship. Back at the office, they return to their easygoing, day-to-day relational habits.

It’s a mistake to begin conversations by trying to convince others of our position, Muehlhoff says. It is better to listen with a sincere desire to understand what the other person believes and why they believe it.

There comes a time in every society when it must face its shadow side — and deal with it.

Societies have myths, legends, and superheroes that lay the foundations for national identity, reinforce beliefs about the self and the other, and shape nations’ collective memory. They exist to make us feel good about ourselves, but as a result, they lie to us and distort collective memory.

As prophets did in the days of abolition, the anti-lynching movement, and the Civil Rights movement, modern-day leaders, like Michelle Alexander, have traversed the country shining light on the myth of equal justice in our justice system.

And on Tuesday, the unlikely duo of Sens. Cory Booker (D – N.J.) and Rand Paul (R – Ky.) joined together to address this myth by introducing the REDEEM Act.

"I will work with anyone, from any party, to make a difference for the people of New Jersey, and this bipartisan legislation does just that," Booker said in a news release. "The REDEEM Act will ensure that our tax dollars are being used in smarter, more productive ways. It will also establish much-needed sensible reforms that keep kids out of the adult correctional system, protect their privacy so a youthful mistake can remain a youthful mistake, and help make it less likely that low-level adult offenders reoffend."

An historic event took place recently in the seaside town of Belfast, Maine. Ten people of vastly different political persuasions — Libertarians, Tea Party Republicans, Democrats, and Progressives — sat in a circle, had a civil dialogue about their hopes and fears for America, and discovered their common ground. Their experience is a model of the local dialogues we so desperately need to build bridges across the political divide.

And yes, one of the 10 is a Buddhist. Judith Simpson, a practicing Buddhist, facilitated the conversation. Judith is an organizational development consultant who has worked with the likes of Eastman Kodak and Corning. She facilitates using a group process called Dialogue. Judith now plies her skills in restorative justice. Dorothy Odell organized the event. She has worked in education as a teacher and as a member of the Belfast School Board. Both reside in Belfast.

“I’ve gotten upset with the media fanning the flames of the story that we’re a polarized nation,” said Dorothy. Judith agreed. Together, they decided to do something about it.

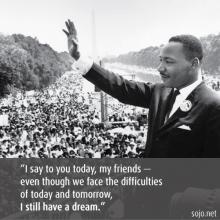

Yesterday was the 50th anniversary of a day that changed America, changed the world, and changed my life forever. I was fourteen years old on Aug. 28, 1963, in my very white neighborhood, school, church, and world. But I was watching. The Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., became a founding father of this nation on that day, so clearly articulating how this union could become more perfect.

He didn’t say, “I have a complaint.” Instead, he proclaimed (and a proclamation it was in the prophetic biblical tradition), “I have a dream.” There was much to complain about for black Americans, and there is much to complain about today for many in this nation. But King taught us that day our complaints or critiques, or even our dissent will never be the foundation of social movements that change the world — but dreams always will. Just saying what is wrong will never be enough the change the world. You have to lift up a vision of what is right.

The dream was more than the Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act, which both followed in the years after the history-changing 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. It finally was about King’s vision for “the beloved community,” drawn right from the heart of his Christian faith and a spiritual foundation for the ancient idea of the common good, which we today need so deeply to restore.

Last night, my wife Janny and I had the honor of sharing a table with a gathering of local Muslims for an Iftar meal. It is currently Ramadan, which means the Muslim community around the globe fasts everyday day from sunrise to sunset. No food. No water. No tobacco. No sex. Each night they have a celebration feast to break their daily fast called the Iftar meal. It is sacred, joyous, and a time to sit with those they love to worship the One they love, Allah (which is simply the Arabic translation of God).

It was into that sacred gathering that they expanded the table and pulled up a seat for us and a few other Christian and political leaders throughout San Diego. Their hope was simply to create space in their daily practice for their neighbors to experience life with them. They were both acknowledging city leaders who have been proactive in creating an environment of dignity and mutual relationship, and creating a space for new/renewed understanding of one another. Acknowledging our core faith differences, they made clear that it should in no way detract from our ability to share a common vision for the good of our city. We are neighbors who live, work, and play on the same streets with a common desire to see deep, charitable relationships, sustainable economy, and mutual understanding and a celebration of diversity.

As I often say, as followers of Jesus, we have no choice but to move toward relationships with those who are marginalized, dehumanized, and in need of love. We don’t compromise our faith by hanging out with people we may or may not agree with. No, in fact, we reflect the very best of our faith.

Skepticism is a good and healthy thing, I told every audience. Be skeptical and ask the hard, tough questions about our institutions — especially Washington and Wall Street. But cynicism is a spiritually dangerous thing because it is a buffer against personal commitment. Becoming so cynical that we don’t believe any change is possible allows us to step back, protect ourselves, grab for more security, and avoid taking any risks. If things can’t change, why should I be the one to show courage, take chances, and make strong personal commitments? I see people asking that question all the time.

But personal commitment is all that has ever changed the world, transformed human lives, and altered history. And if our cynicism prevents us from making courageous and committed personal choices and decisions, the hope for change will fade. Along the way, I got to thinking how the powers that be are the ones causing us to be so cynical. Maybe that is part of their plan — to actually cause and create more cynicism in order to prevent the kind of personal commitments that would threaten them with change.

And this is where faith comes in.

INTRIGUING AND believable characters are part of what makes Janna McMahan’s new novel Anonymitya memorable read. Through the story, which is set in Austin, Texas, the author provides a well-constructed and evenly paced plot that brings to light critical themes around home and homelessness.

Early in the story we discover classic contrasts between the two protagonists. Lorelei is a young, homeless runaway whose daily grind revolves around finding food and a warm, safe place to sleep, while Emily’s major mission centers on branching out from her bartending job to take up a more artistic endeavor as a photographer. One buys organic greens from the high-end Whole Foods Market, while the other seeks sustenance in restaurant dumpsters.

This interesting juxtaposition of characters reels us in. But as we swim through the thickening plot, we discover the startling similarities between the two: Lorelei’s rebelliousness and grit compared to Emily’s disdain for the superficial lifestyle of big-box shopping and Corpus Christi vacations; Lorelei’s refusal to seek help and get off the streets weighed against Emily’s desire to break from the overindulgence she grew up around. As Emily’s mother, Barbara, observes, “Emily liked the frayed edges of life, a little dirt in the cracks.” It should come as no surprise that Emily takes an interest in Lorelei’s hardscrabble existence.

So much about Lorelei remains a mystery, which serves to add tension and compel the reader forward. We sense she is searching for something, and there’s no way to prepare for the powerful punch McMahan delivers when we discover what Lorelei’s quest is about.

I agree with Rev. Wallis — focusing on the common good is a good step toward answering the question of how to be on God's side, and solving many of our nation's greatest points of division. In a country as diverse as ours, however, it can be challenging to know what the common good actually is. As individual participants in society, we all come to the table with different ideological structures for framing our understanding of what is commonly good. Those structures are often built around religion, philosophy, and our beliefs and understandings about existence, mortality, and the cosmos. The situation is exacerbated by the fact that we live in, arguably, the most religiously diverse nation of all time.

Yes, Jesus has called me to love my neighbor as myself, but what does that really mean when my neighbor is Mormon, Muslim, Jewish, Atheist, secular humanist, or Hindu?

Religion is often blamed for the world's greatest conflicts, and rightfully so. One doesn't have to look far to see conflict or violence that is linked to religious motivations or sentiments in some way (think the tragedy at the Boston Marathon or the Sikh man that was murdered shortly after 9/11 because he was wearing a turban). In a country that becomes more religiously diverse every day, it is easy to allow conflict to arise between different religious and non-religious groups. It is true, difference in religious and philosophical ideology can be a cause of great division. But what if I told you it doesn't have to be that way?

I recently went back to the Lincoln Memorial to tell the story of how and why I wrote my new book, On God’s Side: What Religion Forgets and Politics Hasn’t Learned About Serving the Common Good. And I reflected on my favorite Lincoln quote, displayed on the book’s cover:

“My concern is not whether God is on our side: my greatest concern is to be on God’s side.”

I invite you to watch this short video, and to engage in the discussion as we move forward toward our common good. Blessings.

A revealing thing happens when you remove yourself from the daily drum of politics and become a mere observer. I did just that last year, during some of the most divisive moments of the presidential election. Sitting back and watching the deluge of insults and accusations that feeds our political system, I witnessed the worst of us as a nation. And I came to the conclusion that it’s time to reframe our priorities.

When did we trade the idea of public servants for the false idols of power and privilege? When did we trade governing for campaigning? And when did we trade valuing those with the best ideas for rewarding those with the most money?

We’ve lost something as a nation when we can no longer look at one another as people, as Americans, and — for people of faith — as brothers and sisters. Differing opinions have become worst enemies and political parties have devolved into nothing more than petty games of blame.

During a three-month sabbatical, observing this mess we’ve gotten ourselves into, I prayed, meditated, read — and then I put pen to paper. The resulting book gets to the root of what I believe is the answer to our current state of unrest. It is not about right and left — or merely about partisan politics — but rather about the quality of our life together. It's about moving beyond the political ideologies that have both polarized and paralyzed us, by regaining a moral compass for both our public and personal lives — by reclaiming an ancient yet urgently timely idea: the common good.

IT WAS AS if the poison of the rancorous 2012 campaign had seeped into our social groundwater, tainting family gatherings, Facebook feeds, church coffee hours, and workplace lunch rooms. In my lowest moments I pictured an election-result map rendered with myriad fractures, like windshield glass—a nation of particles and fragments, held together, barely, by begrudging surface tension.

How do those of good will find productive and respectful ways to talk about important civic and moral issues when a significant number of people view their fellow citizens as enemies?

Two recent books, by radically different authors, explore how to stay committed to your principles while reaching out and even finding common cause with those who live and believe differently.

ReFocus: Living a Life that Reflects God's Heart, is by Jim Daly, president since 2005 of Focus on the Family. Faitheist: How an Atheist Found Common Ground with the Religious is by Chris Stedman, the assistant Humanist chaplain at Harvard University and an activist in atheist-interfaith engagement. Daly leads a conservative evangelical institution that has been a major player on the Right in the culture wars of the past three decades (including around what Focus would term the "homosexual lifestyle"). Stedman is a young gay atheist who was once attacked by thugs who shouted Bible verses as they tried to shove him and a friend in front of an oncoming train. And yet both men argue, from both pragmatic and ethical grounds, for actively and respectfully engaging those who hold different beliefs.

I AM AGAINST the death penalty in principle. The deliberate killing of prisoners does not demonstrate our society's respect for life, which we are trying to teach—especially to those who violate it. We simply should not kill to show we are against killing. It's also easy to make a, yes, fatal mistake, as alarming DNA testing has demonstrated, revealing some death row inmates to be innocent. In addition, the death penalty is clearly biased against poorer people, who cannot afford adequate legal representation, and is outrageously disproportionate along racial lines. The facts are that few white-collar killers sit on death row, and fewer are ever executed. And there is no evidence that capital punishment deters murder; the data just doesn't show that.

At a retreat I attended a couple of years ago, conservative activist Richard Viguerie approached me and said, "Jim, let's do something together to really shake up politics." Viguerie had become a friend, so I asked him what that might be. "I am a Catholic," Viguerie said. "I am against the death penalty, and I think it's time for conservatives and liberals who agree on that to begin to work together." I was fascinated at the thought of unlikely partners helping to accomplish that together. So we have had several dinner meetings over the last two years with both conservative and liberal leaders—mostly people of faith—to discuss the issue.

Here are some basic facts. There have been 1,312 executions since 1976, when the death penalty was reinstated following a 10-year moratorium. There were 43 prisoners killed in 2011, and 35 so far in 2012. As of April 2012, there were 3,170 people on death row. Forty-two percent are black, 43 percent are white, and 12 percent are Latino. Thirty-three states have the death penalty; 17 have abolished it and several have abolition legislation pending. Since 1973, 141 people have been exonerated and set free from death sentences because of new evidence—people who shouldn't have even been prisoners and were almost killed by the state due to false or faulty evidence. Eighteen of them were released because of DNA evidence. Who knows how many people have been executed unjustly?

Thomas P. O’Neill III, son of Thomas “Tip” O’Neill, former Speaker of the House of Representatives, reminds us of the relationship between his father and former President Ronald Reagan. After describing some of the bruising political battles between the two, he writes:

“Historic tax reforms, seven tax increases, a strong united front that brought down the Soviet Union — all came of a commitment to find common ground. While neither man embraced the other’s worldview, each respected the other’s right to hold it. Each respected the other as a man.

“President Reagan knew my father treasured Boston College, so he was the centerpiece of a dinner at the Washington Hilton Hotel that raised $1 million to build the O’Neill Library there. When Reagan was shot at that same hotel, my father went to his hospital room to pray by his bed.

“No, my father and Reagan weren’t close friends. Famously, after 6 p.m. on quite a few work days, they would sit down for drinks at the White House. But it wasn’t the drinks or the conversation that allowed American government to work. Instead, it was a stubborn refusal not to allow fund-raisers, activists, party platforms or ideological chasms to stand between them and actions — tempered and improved by compromise — that kept this country moving.”

Today, "Values and Capitalism," a project of the American Enterprise Institute, sponsored a full-page ad in Politico (see page 13) in response to the Circle of Protection. While it is encouraging to see another full-page ad urging our nation's legislators to be concerned about the poor, it is unfortunate that the critique of the Circle of Protection and Sojourners work is based on an error.

In Tucson, Arizona, President Obama spoke to the state of the nation's soul. Next Tuesday, January 25, he will speak to the state of the union.