darkness

ACROSS THE UNITED STATES, people will soon be preparing for Thanksgiving. We’ll name what we’re grateful for and then, in an ironic turn, let “Black Friday” convince us we need more. “Cyber Monday” will catch all the credit cards that made it, un-maxed, through the weekend. “Giving Tuesday” lets us pay the virtue toll to keep spending guilt-free on the yet-to-be-named following Wednesday. Whew! The consumerist drive in November and December makes the temporality of liturgical living difficult. But let’s try. November marks the end of both Ordinary Time and the church year. Ordinary Time is the day-in, day-out rhythm of everyday life as we await Christ’s second coming. In these final weeks, we’re not quite waiting on Christ, then — as we do during Advent — so much as we’re preparing ourselves to wait.

Come Advent, the scripture readings will be filled with anticipatory hope. But, as the old church year ends, the passages are full of anxiety and dread. The Hebrew Bible selections spotlight the escalating threat of the coming judgment. Paul’s letters pour out end times panic. Or, as songster Leonard Cohen put it, “Everybody knows it’s coming apart.” In Matthew’s gospel, Jesus forces us to ponder which side we are on. It’s not easy to sit with all this. I want to skip over to Advent hope (or even Christmas joy). But I invite us to hospice the old year’s death throes before welcoming new life at the stable door.

THE DAY A massive electrical blackout plunged Venezuela into darkness, my neighbor Juan Carlos was finally heading back to seventh grade.

It had been four months since he had entered a classroom. His teachers had been missing since November, their $8 a month salary not covering even the commute. Doing the math, I realized that my two hens earned more with their daily eggs.

Leaving his darkened school, Juan Carlos headed straight to the potato field. I watched from the porch as he dropped to his knees to rastrojear—rake the field with his hands to uncover spuds missed in the harvest. The field’s owner turns a blind eye to kids searching for food this way.

And I can’t help but think about my friends on “life” row who live daily in that space. They know that their execution dates can be set at any moment, but they also know that they are alive now and have to live into as much of the fullness of the day as they possibly can. It can be difficult, at times, to sit in the liminal space with my friends, as I never know which they will choose — will they choose life or will they choose death to discuss? And the truth is that they pick both. They need to process their death while they are living. And they have to process their living while they know they face a certain death.

The dimming of the Advent wreath also reminded me of civil rights activist Valarie Kaur’s poignant question: “What if this darkness is not the darkness of the tomb, but the darkness of the womb?” “Remember the wisdom of the midwife: ‘Breathe,’" she says.

As a listener in this space, I choose to sit with them no matter where they are sitting — in the dark or in the light. And maybe, not surprisingly, I have learned more from sitting in the darkness with them. We have all learned by dwelling there. God abides with us as we sit in the darkness. We do not sit alone. The creator of darkness s sits with us. We feel to the marrow of our bones God’s abiding presence. We also know that darkness does not have the final word — light does. . If we will but wait long enough, eventually the sun will come up and the darkness will end.

As she speaks in a voice measured but forceful, Milly challenges us to hold the tension between vulnerability and vigilance in dark times. “We must learn to be vulnerable, she says. “But at the same time, we must be vigilant in the dark.” She reminds us that new life — from a cave or from the womb — comes from the dark and from discomfort, not ease. We must tap into that internal fire, the light that comes from the Holy Spirit.

We feel a deep darkness in our world and in our society right now. We can almost taste it, touch it, and smell it. This darkness invades our souls like a damp, long, December night, bringing a chill all the way inside.

On election night, I hunkered down in my living room, eyes glued to the television, waiting for the announcement. When talking heads announced that Hillary Clinton conceded the election to Donald Trump, my body shook — literally. I could not control it. I had never experienced anything like it. A cry rose from the pit of my stomach and quickly turned into a primal scream.

I am more and more convinced that beauty lies in the margins.

Raised in evangelicalism, we often prayed to reach those who remain in the darkness, that God would open their eyes and see the truth. We had been born again. A veil had been magically lifted off our eyes, welcoming us into the land of all that is bright and right. Like the blind man in the Gospel of John, we proclaim, “I was blind, but now I see.” Those who believe now possess some sort of special knowledge inaccessible to others, and we are tasked to go and lift the blinders off as many as possible.

It sounds a bit arrogant, which has been a common accusation against evangelical Christians. But every conversion experience is a form of turning from darkness to light. An a-ha moment, a lived miracle, a season of wrestling with doubt and crisis that somehow brought the person to a divine encounter with God. These stories ought to be honored and not dismissed. Something has changed, and it is worth celebrating a liberation into hope. I marvel at genuine, earnest faith.

The problem is when we have become blinded by our light.

The first time I really got it, I was 16 years old.

I had traveled by myself to visit distant relatives in Paris, with the hope of improving my French. Somehow, a weekend visit to the beach ended up with me on an unaccompanied trip on a train from a lazy seaside town back to the city. “I’m lonely here, God,” I thought. “Would you show me you are with me?”

Looking out the train window, there was a brilliant sunset hanging over the fields of canola flowers. There was my reminder of God’s love! As the train curved away from the sunset and it fell out of view, I sat back in my seat, satisfied with the gift I had been given … only to start up again as the train took a sharp curve to the left, the sunset back in full view.

“Oh,” I thought, “that’s what they mean by love being abundant and our cups overflowing. I get it.”

The first time I really got it, I was 18 years old.

On my first winter break back from college, I was driving in my parents’ car, listening to the radio. On air was a county executive discussing why a curfew might be a good idea for the county’s youth. According to him, instituting the curfew would help police arrest young people they suspected of other crimes. The implication was that it would only be enforced against those people who looked suspicious. Another voice on the show expressed concerns that what this meant was that the curfew would only be enforced against black teenagers.

“Oh,” I thought, “this is what they mean when they say the police target people they instinctively assume to be suspicious, even if they haven’t done anything wrong. I get it.”

I was scanning my Facebook news feed when I read articles about murders in Iraq.

It seems Islamic extremists in Syria are using beheadings and crucifixions to intimidate opponents. Photos and videos look eerily like scenes from illustrated Bibles.

I read about right-wing hate speeches on the steps of the Massachusetts State House in Boston, stirred by opposition to immigrants but proceeding on to everyone else they hate.

I read about gay bashing in the military. Anti-Semitism in Europe. Domestic violence in Baltimore. And on and on.

I have two responses. First, I applaud those who post such things on Facebook. Cat pictures are fine, but if this ugliness is going on in our world, we need to know about it.

Second, has humanity entered some new depth of degradation? Or do we just know more?

A QUESTION ASKED of me 100 times in the last 10 years: Why do you stay in the Catholic Church? How can you stay in a church where thousands of children were raped around the world? Where men in power covered their ears to the screams of children and moved the rapists around from parish to parish so that smiling welcoming parents presented their awed shy children to the rapists like fresh meat? Where women have been marginalized and sidelined for centuries and their incredible creativity diluted and wasted and left to rot? Where power and greed and cowardice so often trumped the very humility and mercy and defiant belief in the primacy of love on which the church was founded and for which it claims to stand today?

Because, I said haltingly, in the beginning, when I was unsure of my honest answer in the face of such rapacious crime and breathtaking lies, because, because ... because how could I quit now? What sort of rat leaves the ship when it is foundering and your fellow passengers need help? Why would I quit now, of all the times to quit? How could I leave the ship in the hands of the men who nearly sank her? How could I abandon the brave honest mothers and priests and nuns and teachers and bishops and dads and monks and children who are the church, who compose the church, who sing the deepest holiest song of the real church?

Because, I said more and more energetically as the years went by, because there are men like my archbishop in my church, men who stood up to lies and crime and accepted the lash of public insult without a word, though the sins were not theirs.

I’ve always had a curious sort of sympathy for the bad guys. I cried when King Kong died. I wept at Darth Vader’s demise. And I felt like the whole melting thing was a little bit harsh for the Wicked Witch of the West.

Maybe they didn’t really want to be bad. Maybe they were just written that way. Could be that they had a rough childhood, or people made fun of them for being green, or big and hairy, or breathing through a big, black mask. I mean, imagine that on the playground …

Ever since my childhood I’ve felt more comfortable in darkness than most kids seemed to as well. My 10-year-old son won’t even go into any unlit room in our house without being accompanied by our dog, Maggie. But I actually enjoyed being in the dark. It seemed like the one place where I could let the otherwise literal, concrete parts of my brain take a rest, and allow my imagination to run wild.

Theologically, we’re taught to hate, or at least fear, the darkness. We are children of light, God called light into being, and it was from this light that all things were formed. So what use do we have for darkness?

AS THE SEAONS after Pentecost unfolds, we might think that summer calls for a kind of “church lite” in which we shouldn’t expect much to happen. With the dramatic commemorations behind us, the scriptures seem miscellaneous. But this season has its own purpose of soaking in the Word. Just let go of dependence on drama.

Our month’s reading opens in 2 Kings 5 with the healing of Naaman, the distinguished Aramean general, told with a dry humor that Jesus appreciated, since he specifically mentions it (Luke 4:27) in his teaching about faith found outside the bounds of Israel. At first Naaman’s dignity is offended by Elisha not bothering even to meet him in person. His pride receives a further blow in the ludicrous banality of the prescription that Elisha’s assistant passes on: “Go, and wash in the Jordan seven times” (verse 10). Naaman’s fuming about the short shrift he got, and the humiliation of being prescribed a business of splashing in a local stream, are quite comic. Paddling in the Jordan indeed—a ditch in comparison to the storied rivers of Damascus! Smiling, we recognize the storyteller’s shrewd knowledge of psychology. The tale has a good ending. Finally getting off his high horse, Naaman allows his aide to persuade him to try the simple bathing routine. Over time his skin is healed and rejuvenated.

The church behaves like that shrewd aide when it invites us to trust in the power of hearing the scriptures again and again, however overfamiliar some of them seem, and others obscure.

Star Trek: Into Darkness is a fascinating and complicated story that is well worth watching. Instead of providing a summary, I want to explore three related aspects of the movie: sacrifice, blood, and hope for a more peaceful future.

Live Long and Prosper – The Sacrificial Formula

In a reference to my favorite Star Trek movie, Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan, the current movie’s Spock (Zachary Quinto) restates the sacrificial formula: “The needs of the many outweigh the needs of the one.” This formula has generally been used throughout human history to justify sacrificing someone else. As René Girard points out, from ancient human groups to modern societies, whenever conflicts arise the natural way to find reconciliation is to unite against a common enemy.

Of course, there’s a lot of this going on throughout the Star Trek franchise. One conversation in Into Darkness explicitly points this out when Kirk (Chris Pine) unites with his enemy Khan (Benedict Cumberbatch), and explains it to Spock:

Kirk: The enemy of my enemy is my friend.

Spock: An Arabic proverb attributed to a prince who was betrayed and decapitated by his own subjects.

Kirk: Well, it’s still a hell of a quote.

JEREMY SCAHILL SPENT years working out his notions of social justice in homeless shelters and conflict zones and among peace activists. In 2007, Scahill’s award-winning investigative reporting made waves when he published Blackwater: The Rise of the World's Most Powerful Mercenary Army, a comprehensive exposé on the secret role of private military contractors in the United States’ “war on terror,” which prompted several congressional inquiries. Scahill’s newest book, Dirty Wars: The World is a Battlefield, digs into the obscure underbelly of U.S. covert wars.

“In one of my trips to Yemen, I traveled in the south of the country where most of the U.S. drone strikes in Yemen have happened,” Scahill said during a recent visit to Sojourners’ Washington, D.C. office. “I was interviewing a number of tribal leaders. This guy from Shabwa province said to me, ‘[Americans] consider al Qaeda [to be] terrorism. We consider your drones [to be] terrorism.’ I heard that over and over in a variety of countries. ... Many people, in Yemen or in Somalia, would not be predisposed to think of al Qaeda as anything positive. Al Qaeda is a reviled organization in Yemen. ... But there are tribal leaders who are saying, ‘You know, you pushed us into a corner where our people are now sympathetic with al Qaeda.’ After years of traveling in these countries, I really believe that we’re creating more enemies than we’re killing.”

In some respects, drones are simply a new tool of old empire. Scahill’s book title, Dirty Wars (and film of the same name), is partly “a macabre tip-of-the-hat to the dirty wars in Central America, fueled by the United States ... targeting people who are insurgents and claiming they were communists. The new version of this is targeting people who are fighting us and claiming they’re al Qaeda.”

FROM THE RIVER to the rope. From the creek to the cross. From the dove and a "voice from above" to death by state execution and profound silence.

This is Lent. This is the Jesus Road, the Christian way. O Lord, how can we follow you?

Lent is time of remembering ourselves. In the ancient church, those preparing for baptism were publicly challenged: Do you renounce your bondage to Master Satan? Do you reject the slave-mind and all its glamour and subtle temptations? Will you allow Christ to buy your freedom?

The catechumen turned to face the east and the dawn, answering: "I give myself up to thee, O Christ, to be ruled by thy precepts."

It is Lent. We go down to the river to pray. We step into the waters of repentance. We surface as a new creature in Christ. From that moment onward, we imprint on Jesus. This is our survival strategy as newborn disciples. We follow him, like ducklings behind their mother.

After his baptism in the Jordan River, Jesus is driven straight out—into the unloved places, into the wilderness. There he is pricked by demons to toughen him up. He is being prepared. He must look into his own despair. Satan is the supreme surgeon for separating us from our hope.

As I stood in line at Orlando International Airport, a little girl did not want to go through airport security. She was desperately clinging to her grandmother.

I had already been pondering, as I *always* do, the enormous investment the nation has made in these checkpoints, going on 12 years now, in response to the actions of 19 men. 19 persons. These lines are here forever now, just one more cost of the fall, one more insult to our usual illusion of normalcy.

I'm not inconvenienced by the searches or the scanners, or worried about my personal liberties, though half stripping in public is embarrassing (we men have to take our belts off). At least the posture in those full-body cylinders reminds me that, at a very real level, this ought to be my more constant pose: found wanting, presumed guilty, and in need of throwing up my hands in surrender.

Still, I marvel at the sheer amount of money we must spend for all of this equipment and personnel, hoping this all somehow makes us safe. I'm skeptical.

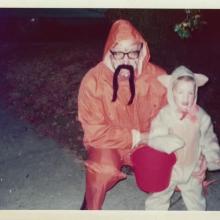

One of my most vivid childhood memories of Halloween 1977, the year my family moved to a new town in Connecticut right after the school year had begun. I don't recall what my costume was, but I do remember going door-to-door with my father, meeting new neighbors and collecting a heavy bag of candy, as the suburban warren of Cape Cods and manicured lawns morphed into an other-worldly fairyland.

I was 7 years old and the new kid on the block, so when the cover of darkness fell at sunset, I hadn't a clue where I was. As my father deftly navigated our way home in the crisp autumn night, it felt like he had performed a magic trick. When the morning came, I couldn't believe that our adventure the night before had been on these same streets. To my young imagination (and heart) it felt as if we had been walking through Narnia or Rivendell rather than a sleepy New England suburb.

A few years after that, my family stopped celebrating Halloween. We had become born-again Christians and our Southern Baptist church frowned on the practice. Halloween, I was taught, was an occult holiday (or maybe even Satanic!) and good Christians should have nothing to do with it.