homogeny

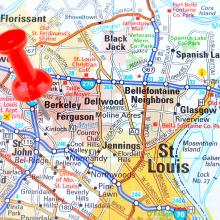

I am white. Most of the people near my house are white. This is the way it is for most of us white people in the U.S., and as we continue to be shown, the consequences are both critical and countless.

While the Fair Housing Act of 1968 prohibits all forms of housing discrimination, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development estimates that millions of instances occur each year, thus residential segregation continues to be a common facet of modern day life. To put it simply, white people tend to live by other white people, and it is the way it is by no accident.

Segregated neighborhoods are often reinforced by the practice of racial “steering” by real estate agents, or when landlords deceive potential tenants about the availability of housing or perhaps require conditions that are not required of white applicants. In addition, lending institutions have been shown to treat mortgage applicants differently when buying homes in non-white neighborhoods in comparison to their attempt to purchase in white neighborhoods. As a result of such practices, white people tend to live in a state of residential separateness, for as the most recent U.S. Census date confirms, genuine racial integration is — for the most part — alarmingly rare.

Of course, our own behaviors contribute to our current state of affairs. White people seem to prefer housing located by other white people. As a result, far too many white people are willing (and able) to pay a premium to live in predominantly white neighborhoods. So equivalent housing in white areas commands a higher rent than others, and through the process of bidding-up the costs of housing, many white neighborhoods effectively shut out people of color, because those without white skin are more often unwilling (or unable) to pay the premium price to buy entry into such white neighborhoods. As a result of such white flight and isolation, not only do we witness a rise in racial ignorance and indifference, but it also leads to increased injustice in the form of disproportionate hostility directed at people of color.

Whenever I hear the term Common Good I think of Thomas Paine’s infamous pamphlet Common Sense,which challenged the British government and the royal monarchy, but did not challenge the institution of slavery. As an African-American woman I enter the Common Good conversation cautiously because I know that in our society we have a habit of taking what is good for Western hegemony and making it the standard for everyone else.

As we pursue the Common Good, let us remember what was once considered common and good during earlier points in American history: chattel slavery, indigenous genocide, and institutionalized sexism. To truly come to a Common Good, we need to honor a diversity of voices and challenge our assumptions about what is common and what is good. Our default is to take what is good for our culture, gender, or community and make it the common standard for all. I have experienced being invited into organizations that were aiming to do good in the world, but an expectation existed that I would be silent about my unique concerns as an African woman. I know that denying my reality can never be good for my spiritual, physical, or social well being.