income inequality

Public health professionals strive to bridge the gap between good intentions and good outcomes. Learning about public health will equip Christians to think on a systems level, to have evidence-based programs, champion accountability, and partner with people most affected to accomplish systemic change.

“JOHN, THERE'S, UH, A GUY YOU NEED TO COME SEE see in the sanctuary. I think he’s angry or upset or something.” Hearing these words on a Sunday morning while I sat in my office preparing for worship meant one thing: Someone needed money. One of the hazards (or opportunities) of working in a downtown church was that the steeple and columns out front signaled to people that they should drop in when they needed a few dollars. I became the go-to minister on staff to greet these visitors.

I heard the man before I saw him. His sobs were audible over the only other noise in the space, the women arranging flowers for our 10:30 a.m. service. He was seated in the next-to-last row of the opulent sanctuary built in 1924. White and in his 40s, the man looked put-together but sweaty, his denim jacket well-worn. I introduced myself, told him I was glad he’d come to our church that morning, and asked if there was anything I could do for him. The man—I’ll call him James—told a familiar story: He’d arrived from out of town, didn’t know anyone in Winston-Salem, and was currently living at a shelter down the street. “I just don’t know what I’m going to do. I’m desperate,” he said at a volume that caught the attention of the flower arrangers. “I need some money for a bus pass and I’ve got to find work. I don’t know why God would do this to me.”

“This,” he said pointing to the piece of paper in his hand, “this is all I want. How can I get this?” He was holding a flyer for our discontinued financial literacy class. I told him we no longer offered the class and didn’t have any funds available for assistance.

I drive a car, go on vacation, and eat at restaurants with friends. I have health insurance, a bank account, and a job. I knew I ought to help the man, but I didn’t. Our church’s policies around requests of this kind required more oversight than I could give at that moment, and my mind drifted to the other duties I had that morning. I invited him to stay for worship and told him if he came back later in the week, I might be able to refer him to some agencies that could help.

James stayed for the service, sobbing quietly on occasion. In the months that followed, I saw him around downtown, but never again in the sanctuary. I felt disappointed for failing to offer help, for getting caught between conviction and institutional responsibility. As someone who works in ministry, often with poor people, I’ve learned to live with that feeling to get through my work. Yet I don’t want to make peace with that feeling; doing so would be giving up too easily.

TWENTY YEARS AGO, when we talked about the “digital divide” we meant things like low-income people’s access to computers and the internet. But according to a recent study from Common Sense Media, that turn-of-the-century gap has largely closed. Seventy percent of families with an annual household income below $30,000 now have a computer at home, and 75 percent have high-speed internet access. In addition, low-income families are near the national average for access to mobile devices such as smart phones and tablets.

But another digital divide is emerging that could have more dangerous long-term consequences.

Researchers have discovered a lot about how brain development and personality formation happen, and their lessons keep coming back to the importance of real-world experiences and face-to-face human interactions, especially in the childhood years. To avoid passivity and mental laziness in their children, many high-income parents are starting to limit their children’s time on digital devices. Common Sense Media found that the children of upper-income families spent half as much time in front of screens as did children of low-income families.

Several private schools are even dialing back their reliance on digital technology. Meanwhile, in many public schools, students are being issued Chromebooks or iPads and shunted into online learning programs. According to Education Week, American schools spend $3 billion per year on digital content, as well as $8 billion-plus yearly on hardware and software, with little to show for it so far in the way of improved learning.

THE RICHEST EIGHT people in the world, according to an Oxfam report this January, own more wealth between them than the poorest 50 percent of humanity—3.6 billion people.

Let’s make that clear: Eight people own more wealth than 3.6 billion people. That is simply grotesque. And it is the type of fact that needs to break through the complacency and routine of our daily lives, and the latest outrages of the U.S. president, and spur us to demand effective collective action to change course.

Many people don’t spend much time thinking about the difference between income inequality and wealth inequality, but it’s important to understand that wealth inequality is both harder to fix and harder to justify, and it has enormous consequences that resonate over multiple generations. The reality that the Oxfam report makes plain is that even while global extreme poverty has seen dramatic reductions over the last couple of decades, global wealth continues to be concentrated at the very top, into fewer and fewer hands.

The recovery of global financial markets since the crash of 2008 has been very good for the already wealthy, but for those who didn’t have many assets to begin with, the recovery of the stock market has benefited them far less. To put it bluntly, the class of the people who had the most to do with causing the crisis ended up benefiting the most from it.

For much of its long history in the U.S., the Catholic Church was known as the champion of the working class, a community of immigrants whose leaders were steadfast in support of organized labor and economic justice – a faith-based agenda that helped provide a path to success for its largely working-class flock.

In recent decades, as those ethnic European Catholics assimilated and grew wealthier, and as the concerns of the American hierarchy shifted to battles over moral issues, such as abortion and gay marriage, traditional pocketbook issues took a back seat.

Perhaps the most surprising finding is that the pay gap does not diminish (and may grow wider) when we take into account education and experience. Women in the clergy tend to be better-educated than their male colleagues. As a result, when we take into account age, years of schooling, and having a theology degree, the number becomes 85 cents.

In other words, female clergy really do earn less for the same education and experience.

Image via maradon 333/Shutterstock.com

On Oct. 27, 1994 — 21 years ago today — the U.S. Department of Justice reported that the United States’ prison population had reached over 1 million people. By comparison, that’s the same size as San Jose, Calif.— the tenth biggest city in the US.

Today, the United States’ prison population is over 1.5 million — the size of Philadelphia, Pa., our nation’s fifth largest city.

Yet the size of our prison population — the largest in the world — is only part of the problem. Communities of color and poorer communities are disproportionally sentenced to prison — the result of systemic injustices including income inequality, school-to-prison pipelines, and racial profiling.

We mark many positive anniversaries here at Sojourners, but the work of justice also necessitates recognizing ongoing abuses of human dignity over time. So today, on the grim anniversary of 1 million people housed in our prison system, we choose to remember them and all those still behind bars. Here are ten articles we’re re-reading today about mass incarceration — and how to end it.

The city council of Los Angeles agreed to draft a plan to raise the city's minimum wage to $15 on Tuesday, the LA Times reports.

The plan would raise minimum wage by $6 — from $9 an hour to $15 — by 2020 for some 800,000 workers.

Not all are in favor of the plan, according to the LA Times:

The council’s decision is part of a broader national effort to alleviate poverty, said Maria Elena Durazo, former head of the Los Angeles County Federation of Labor. Raising the wage in L.A., she said, will help spur similar increases in other parts of the country.

Some labor leaders have expressed dissatisfaction with the gradual timeline elected leaders set for raising base wages. But on Tuesday the harshest criticism of the law came from business groups, which warned lawmakers that the mandate would force employers to lay off workers or leave the city altogether.

“The very people [council members’] rhetoric claims to help with this action, it's going to hurt,” said Ruben Gonzalez, the Los Angeles Area Chamber of Commerce’s senior vice president for public policy and political affairs.

Los Angeles joins Chicago, San Francisco, and Seattle in raising the wage in recent months. Read more here.

Jesus was quite clear that our allegiance was to be with the POOR, not the barons of Wall Street.

God's laws are immutable Gravity. Aging. Those sorts of things. We cannot change them. But we DO know that mere humans MADE UP the laws of the market economy and we don't have to follow its rules. We can choose to, but it’s a choice.

The rules that run our capitalistic system were invented by us. And we really do not have to play by those rules.

(Spoiler—and imperfect analogy — alert to anyone who wasn’t able to sneak these books when they were pre-teens)

If there was one book series that defined my childhood/pre-adolescence, it would be V.C. Andrews’ Flowers in the Attic series. OK, maybe that wasn’t THE book series—after all, there were the Baby-sitters Club books and Sweet Valley High—but in terms of helping to destroy what little innocence I still had, Flowers in the Attic gets top ranking. I mean, I probably didn’t need to be reading books about incest, child abuse, and religious fanaticism when I was 10 years old. But that’s a story for another time.

The Lifetime network has made a film version of Flowers in the Attic that will debut on Saturday night. In anticipation of the remake, I decided to watch the 1987 version starring Kristy Swanson. Besides being struck by how dated it was — think fuzzy lighting, a lot of beiges and pastels, and 80s bangs — the premise seemed outdated even for that time. A recently widowed stay-at-home mother of four finds herself unable to care for her family and must return to her wealthy, estranged parents and beg to get back into her dying father’s good graces (and will). As a condition of her return, she must consent to have her four children locked in the attic and subjected to her mother’s abuse and neglect.

I sometimes forget how much the world has changed in such a short period of time.

About a year ago, I wrote about my family participating in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) Challenge, which encourages families to try to live on the equivalent of SNAP assistance (food stamps) for one week. It was a growing experience for all of us, and we actually fell short of our intended goal. It turns out that it’s not easy to feed a family of four well — especially without great time and effort — on less than $20 a day.

In looking back on that experience, a number of myths come to mind that I’ve heard from folks about SNAP, which I thought I’d share here.

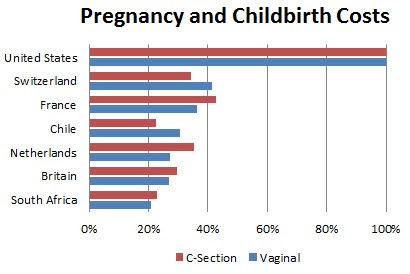

"American Way of Birth, Costliest in the World"

That's the headline of an article by Elisabeth Rosenthal in yesterday's New York Times. The article includes a chart comparing childbirth costs in seven countries. In the United States, the average amount paid for a conventional delivery in 2012 was $9,775; for a Caesarean section, it was $15,041. Those are the highest prices for childbirth anywhere in the world.

To get an idea of just how high, I made a chart using the figures in the NYT chart. Childbirth costs in the other six countries range from 21 percent to 43 percent of U.S. costs even though American women typically spend far less time in hospital.

South Africa is so dangerous for childbirth that its graph line would not fit on this blog page. For every 1,000 births, there are 56 infant deaths. For every 100,000 births, there are 400 maternal deaths. [Chart by L. Neff; data from WHO]

Earlier this month, I went to vote at our local middle school in North Durham. It was one those winter-tease days, colder than usual, a glimpse of the coming months in North Carolina. As I walked into the school’s auditorium, I was met by poll monitors with visible breath and bundled-up like Ralphie’s brother from the movie A Christmas Story. For a Midwesterner, cold temperatures in North Carolina is a warm day in the fall, nonetheless, it was clear the monitors as well as voters were uncomfortable and frustrated with the conditions. While searching for my name in the voter list, I overheard one monitor pleading with an administrator to get the heat turned on, fearing the cold atmosphere might shoo voters away.

When I left the facility, I couldn’t help but wonder at the irony of the situation. In a crucial election with many issues at stake, including tax fairness, our local voting facility struggled to provide reasonable and comfortable conditions for the voters. It might be unfair to assume that the lack of heat in the earlier morning hours is related to the school’s budget, and subsequently, tax revenue. Perhaps the custodian simply forgot to turn it on. But, as national, state, and local governments continue to cut back on budgets and programs due to the lingering recession’s effects on revenue, the public sector and often those in lower-income neighborhoods are taking the brunt of tax policies and restructuring.

Think Progress reports:

Income inequality has grown in nearly every state in the country over the last three decades and continues to climb across the nation, according to new report from the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities and the Economic Policy Institute.

While a slow recovery from the Great Recession for middle- and low-income families has exacerbated income inequality in the short-term, government policies that are preferential to the wealthy and the long-term stagnation of wages have caused significant growth in the gap between the wealthiest 20 percent of Americans and the poorest fifth, the report found. Across the country, the richest 20 percent make eight times more than the average income of the bottom 20 percent, a ratio that didn’t exist in a single state 30 years ago:In the United States as a whole, the poorest fifth of households had an average income of $20,510, while the top fifth had an average income of $164,490 — eight times as much. In 15 states, this top-to-bottom ratio exceeded 8.0. In the late 1970s, in contrast, no state had a top-to-bottom ratio exceeding 8.0.

Read more here.

The U.S. Census Bureau released its 2011 poverty report this morning, reporting that 46.2 million people were living in poverty, amounting to 15 percent of the population. Neither was significantly different than 2010. All major demographic categories – white, African-American, Hispanic, Asian – were also essentially the same as last year.

The number of children and the elderly in poverty remained the same.

Duke professor Dan Ariely writes for The Atlantic:

The inequality of wealth and income in the U.S. has become an increasingly prevalent issue in recent years. One reason for this is that the visibility of this inequality has been increasing gradually for a long time--as society has become less segregated, people can now see more clearly how much other people make and consume. Owing to urban life and the media, our proximity to one another has decreased, making the disparity all too obvious. In addition to this general trend, the financial crisis, with all of its fall out, shined a spotlight on the salaries of bankers and financial workers relative to that of most Americans. And on top of these, and most recently, the upcoming presidential election has raised questions of social justice and income disparities, bringing the issues into focus even more.

Check out the piece for more insight

In a thought-provoking piece for Al Jazeera, Yale lecturer John Stoehr writes:

According to a study by the Center for American Progress, there is a striking correlation between the decline of infrastructure and the rise of inequality over the past four decades. In other words, the more money going to the top income earners, the more the rest of us deal with potholes, decrepit bridges, rusting rail cars and the rest.

Read the full piece here