indigenous peoples

This article is adapted with permission from Becoming Kin: An Indigenous Call to Unforgetting the Past and Reimagining Our Future by Patty Krawec. © 2022 Broadleaf Books.

I WAIT AT the back of the stage, behind the curtains, holding my hand drum and listening to the low buzz of a theater filled with people. My friend Karl stands in the darkness at center stage, waiting for me to start singing and make my way to where he stands. We are providing an opening for the Niagara Performing Arts Center’s season preview. It is not a Native event. The center is a public arts venue that showcases a wide range of performers, and the artistic directors include Native artists throughout the regular season. They have asked Karl and me to open this particular night as an acknowledgment that this and future events take place on Haudenosaunee and Anishinaabe land.

It is fall 2017, 150 years since Canada’s confederation, and I’ve made a ribbon skirt to wear at this event. Ribbon skirts—long cotton skirts embellished with rows of ribbon and sometimes with appliqued designs—are a contemporary innovation of an older style of clothing that we wore before settler contact. The ribbon skirt I’ve made for this evening is black with wide ribbons in the colors associated with the medicine wheel: red, black, white, and yellow. I have appliqued red maple leaves falling down the front of the skirt until they are covered by ribbons. I like the imagery of Canada being absorbed by Indigenous ideas. Later, during the gathering after the event, a couple of women will come to speak with me. They will comment that the leaves are upside down. A nation in distress flies their flag upside down, I will tell them. And Canada, like the United States, is a nation in distress.

There is the beat of the drum in that darkened theater and then my voice coming from the back of the stage. I move toward the front, singing each verse louder as the lights come up. When I finish, Karl speaks the words of the Haudenosaunee Thanksgiving Address in Oneida. Then we simply leave the stage. Not explaining the song or our actions or our words is deliberate. We let the audience sit for moment and consider that what feels profoundly alien to them is not alien at all. For one brief moment, they are surrounded by the sounds of this place.

That evening before we go on stage, Karl and I talk about whether Christianity and Indigenous worldviews can ever be reconciled, if there is any common space. He doesn’t think so. Karl is Oneida and part of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy. Hundreds of years ago, when it became evident that the newcomers were going to stay, he says, the Confederacy made a treaty with the settlers called the Two Row. This is written in the form of a wampum belt made of oblong purple and white beads, with two white rows on a purple background. The agreement was that we would travel together, the Indigenous peoples and the settlers, each in our own boat but on parallel paths in a relationship guided by peace, honesty, and respect.

The principle of noninterference lives at the root of many Indigenous philosophies and is exemplified in treaties like the Two Row: We would live according to our ways, and the newcomers would live according to theirs. Although colonization is clearly a violation of this treaty, the Haudenosaunee people I know remain committed to it and continue to try to live within these principles.

I watched both of the Democratic presidential debates over the last two nights, waiting to see if anything related to the invisibility of Indigenous peoples would somehow make its way into the conversation. I didn’t expect it to, of course; in a nation that does not even begin its events with a land acknowledgement (like Canada, Australia, and other nations do), why would we expect that the experiences of the original peoples of this land would come into a debate when each candidate only has a limited time to respond?

Image via mythja/Shutterstock.com

When we think about the meeting of the first pilgrims and the Native Americans, we usually connect vicariously to one side of that old Plymouth encounter, mysteriously linking our faith journey to the early pilgrims’ faith journey. But what about those long-ago Native Americans? Is there a reason to remember them as more than a foil for the pilgrims?

Year after year we think warmly of that first union of the pilgrims and the Native Americans — and then we continue on in the supposed faith tradition of one of those peoples without another thought to the fate of the others.

So what role do those old Native Americans play in our faith today, and how might we bring them to mind or honor them? Here are a few ways you can faithfully honor both sides of the Thanksgiving table this year.

In November, Sister Maureen Fiedler hand-delivered a letter to Pope Francis’ ambassador in Washington, D.C., urging the pontiff to renounce a series of 15th-century church documents that justify the colonization and oppression of indigenous peoples.

She doesn’t know if the letter made it to the Vatican. But she’s hopeful a recent resolution by the Leadership Conference of Women Religious will spur the pope to repudiate the centuries-old concept known as the “Doctrine of Discovery.”

“When I learned about it, I was horrified,” said Fiedler. As a member of the Loretto Community, a congregation of religious women and lay people, Fiedler first heard of the doctrine when her order marked its 200th anniversary by challenging “the papal sanctioning of Christian enslavement and power over non-Christians.”

We have a responsibility to use the Earth's wealth relationally, not exploitatively.

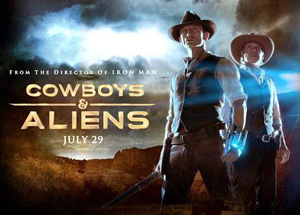

THE DOMINANT cultures of North America have long struggled to take responsibility for the suffering and injustice inflicted upon the Indigenous Peoples of the continent. The archetypal “us/them” story of cowboys and Indians remains at the core of North American national identities, from derogatory sports mascots and symbols such as the Washington “Redskins” and the “Chief Wahoo” character of the Cleveland Indians to the ignorant “redfacing” by non-Indigenous partygoers and trick-or-treaters in contrived Indian outfits. And this situation is nowhere near ending, despite many years of cultural sensitivity training and education.

Such overt racism should never be acceptable today. Yet it persists in regard to Indigenous Peoples. Why is this? As one friend remarked to me, most modern-day Americans believe injustices done to Indigenous Peoples to be a thing of the past.

But are they? Steve Heinrichs, director of Indigenous relations for the Mennonite Church in Canada, has brought together nearly 40 theologians, activists, writers, and poets—half of whom are Indigenous—to create Buffalo Shout, Salmon Cry: Conversations on Creation, Land Justice, and Life Together, a challenging anthology on Indigenous-Christian relations, stolen land, racism, and the impending environmental crisis that we all must face together.

In December, I will be hosting a public reading of the 2010 Department of Defense Appropriations Act in front of the Capitol in Washington, D.C.

I am doing so because page 45 of this 67 page document contains a generic, non-binding apology to native peoples on behalf of the citizens of the United States.

The text of the apology included in the defense appropriations bill reads:

Apology to Native Peoples of the United States

Sec. 8113. (a) Acknowledgment and Apology- The United States, acting through Congress —

(1) recognizes the special legal and political relationship Indian tribes have with the United States and the solemn covenant with the land we share;

(2) commends and honors Native Peoples for the thousands of years that they have stewarded and protected this land;

(3) recognizes that there have been years of official depredations, ill-conceived policies, and the breaking of covenants by the Federal Government regarding Indian tribes;

(4) apologizes on behalf of the people of the United States to all Native Peoples for the many instances of violence, maltreatment, and neglect inflicted on Native Peoples by citizens of the United States;

(5) expresses its regret for the ramifications of former wrongs and its commitment to build on the positive relationships of the past and present to move toward a brighter future where all the people of this land live reconciled as brothers and sisters, and harmoniously steward and protect this land together;

(6) urges the President to acknowledge the wrongs of the United States against Indian tribes in the history of the United States in order to bring healing to this land; and

(7) commends the State governments that have begun reconciliation efforts with recognized Indian tribes located in their boundaries and encourages all State governments similarly to work toward reconciling relationships with Indian tribes within their boundaries.

This apology was not publicized by the White House or Congress. As a result, a majority of the 350 million citizens of the United States do not know they have been apologized for, and most of the 5 million Indigenous Peoples of this land do not know they have been apologized to.

On December 19, I am hosting a public reading of the 2010 Department of Defense Appropriations Act. I am doing so because page 45 of this 67-page document contains a generic, non-binding apology to native peoples on behalf of the citizens of the United States.

This apology was not publicized by the White House nor by Congress. As a result, a majority of the 350 million citizens of the United States do not know they have been apologized for. And most of the 5 million Indigenous Peoples of this land do not know they have been apologized to.

... This apology is a part of our country's history. Our leaders wrote it, the 111th Congress passed it, and President Barack Obama signed it into law. Then, unfortunately, they buried it. I am not protesting this, nor am I celebrating it. I am merely attempting to publicize it in the most open, respectful, and sincere way I know how.

Americans have a hard time knowing how to respond to the sins of our colonial past. Except for a few extremists, most people know on a gut level that the extermination of the Native Americans was a bad thing. Not that most would ever verbalize it, or offer reparations, or ask for forgiveness, or admit to current neocolonial actions, or give up stereotyped assumptions -- they just know it was wrong and don't know how to respond. The Western American way doesn't allow the past to be mourned or apologies to be made. Instead we make alien invasion movies.

Americans have a hard time knowing how to respond to the sins of our colonial past. Except for a few extremists, most people know on a gut level that the extermination of the Native Americans was a bad thing. Not that most would ever verbalize it, or offer reparations, or ask for forgiveness, or admit to current neocolonial actions, or give up stereotyped assumptions -- they just know it was wrong and don't know how to respond. The Western American way doesn't allow the past to be mourned or apologies to be made. Instead we make alien invasion movies.