minority

On Sept. 13, Pew Research Center released four hypothetical scenarios that model what the religious landscape of the United States might look like if current demographic trends continue. The four models projected that the U.S. population who identify as Christian would decrease from 64 percent in 2020 to between 35-54 in 2070.

While the Iraqi conflict is far from over — a battle is now raging in the strategic city of Mosul, although government forces have gained ground against Islamic State militants — Mirkis focused many of his remarks on how to heal his deeply divided country.

Exit polls suggest 81 percent of white evangelicals voted for President-elect Donald Trump.

But support for Trump may have been less decisive on Christian college campuses, where most students are also white evangelicals.

A Washington Post/ABC News poll, before the election, found the views of younger adults do not align with some older ones, when it comes to their beliefs about Trump supporters.

I am upset by the results of the election, and I am particularly saddened that 81 percent of white American evangelicals got into bed with a monster on Nov. 8. But I am also encouraged and have not lost hope.

Here’s why:

Around 11:15 p.m. Tuesday, my 15-year-old daughter, frustrated by all she was seeing on the television, stormed out of the room and announced: “Dad, I am going to bed. I am embarrassed for my country.”

(Editors’ Note: Sojourners is running an ad in Rep. King’s district. Watch the ad and click here to learn more about it.)

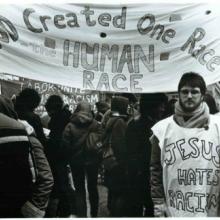

Business leaders, law enforcement officials, and evangelical Christians—key constituencies that are typically part of the Republican base—have been at the forefront of immigration reform. Given the obvious benefits of, and broad public support for, immigration reform, why are many arch-conservatives in the House of Representatives refusing to address the issue in a serious way? The answer may point to an issue that we still hesitate to talk about directly: race.

Fixing our broken immigration system would grow our economy and reduce the deficit. It would establish a workable visa system that ensures enough workers with “status” to meet employers’ demands. It would end the painful practice of tearing families and communities apart through deportations and bring parents and children out of the shadows of danger and exploitation. And it would allow undocumented immigrants—some of whom even have children serving in the U.S. military—to have not “amnesty,” but a rigorous pathway toward earned citizenship that starts at the end of the line of applicants. Again, why is there such strident opposition when the vast majority of the country is now in favor of reform?

When I asked a Republican senator this question, he was surprisingly honest: “Fear,” he said. Fear of an American future that looks different from the present.

Time was when a determined minority vowed to change the nation’s collective mind about racial integration and the Vietnam War.

I was in that minority. We considered our cause just. We called our tactics “civil disobedience,” “grass-roots organizing,” “protest,” “civil rights,” “saving America.”

It’s a bit disingenuous now for us to lambaste a conservative minority for wanting the same leverage and for using the same tactics. “Civil disobedience” can’t be relabeled “obstructionism” just because the other side is using it.

Every morning, Leo's smile brightens the cafeteria at my elementary school. He hobbles in, holding his teacher's hand. His eyes squint at the bright lights. He squirms at loud noises. And always, he smiles.

"Good morning, Leo," I say as I rub his cheek and look into his eyes. He looks back into my eyes for a split second, then gazes off into his own world. That one-second look is his way to say good morning. Leo is a non-verbal first-grader. He is a student in our K-2 trainable mentally disabled class. He comes to us with Down Syndrome, autism, and wonder.