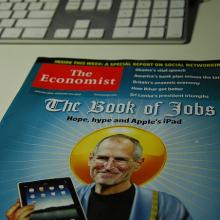

steve jobs

ON JAN 9, 2007, STEVE JOBS stepped onto a stage in San Francisco, his trademark black mock-turtleneck blending with the shadowed backdrop, his clipped hair and lean countenance offering a monk-like silhouette against the screen.

Jobs stepped forward and raised his arms. And there it was, almost inconspicuous in the palm of his hand. “Today, Apple is going to reinvent the phone ... here it is ... the iPhone.” Naming a new god.

At the time, no one consciously believed that smartphones, the internet of things, or ubiquitous computing would save us. Yet, as the encyclical Laudato Si points out about technocracies: No one has to actually believe they’re gods. They become gods when we start investing our hope and identity in them.

And here we are. We live as if the connections provided by digital technologies are vital—and indeed we have made them so.

A decade after the first iPhone, environmental engineer Braden Allenby was asked whether, one day, humans would be wired directly into the internet. “Look at any city street,” he replied. “At least half the people are looking at their phones. We’re already integrated into networks beyond our physical environment.” Heads bowed, praying to strange new gods.

It began as allure: more accessible music, easier communication, maps and directions. Then it slid toward addiction: picking up the phone in the morning, like a first cigarette of the day. And now, dependence: Our lives are synced, our habits surveilled, our data monetized, and the world goes ’round. Our little intimacies power a vast machinery.

All in the name of improving our lives.

wongwean / Shutterstock

MICHAEL FASSBENDER'S uncanny performance as Apple Inc. co-founder and CEO Steve Jobs begs the question of how someone so clueless about human relationships could win the hearts of so many people. Of course, the performance and the Aaron Sorkin script it’s based on are not the same thing as the man himself. Steve Jobs may be unfairly treated by Steve Jobs. The question of its accuracy is not unimportant, and people who knew him deserve a hearing. But the film only sketches a persona rather than providing an encyclopedia of the soul.

Treating Steve Jobs as a film about power and personality evokes the Quaker teacher Parker Palmer’s notion of an “undivided” life. Palmer quotes Rumi’s warning, “If you are here unfaithfully with us, you’re causing terrible damage.” One facet of this unfaithfulness is the difference between living “from the inside out” and living primarily for external reward. Undivided lives are punctuated by initiatory experience, familiar to our ancestors, and now re-emerging in communities such as the ManKind Project and Woman Within. Initiatory experiences take people into the depth of their psyches, supported by wise elders, opening a crack that lets in the light of transformation. Initiated egos thrive in balanced service to the highest self and the common good (so the wise elders tell me).

The Steve Jobs in Steve Jobs has no such initiation—he seems basically the same shallow egotist at the end of the movie as he was at the start. The joy of Steve Jobs is the kinetic dance of image and sound, and actors at the top of their game (Kate Winslet as the definition of long-suffering colleague, Seth Rogen in a rare dramatic role, and Michael Stuhlbarg, all of them representing prickly conscience). The problem of Steve Jobs is that it omits engagement with the personal transformation that many think unfolded for him as his products achieved something like omnipresence. There’s no initiation here, unlike in Bridge of Spies, where Tom Hanks risks his life to negotiate a prisoner swap in a gripping, if light, Cold War thriller. Mark Rylance’s accused Soviet spy emerges more humanized than Jobs’ community-building entrepreneur.

The new movie about Steve Jobs is short on anything explicitly religious. Like its main character, however, it’s got a thread of transcendence running through it.

The truth about Jobs and religion may be that, in this arena as in others, he was ahead of the cutting edge.

The film isn’t making the purists happy, in part because it takes too many liberties with history. But it’s not a documentary. I’ll go against many of the reviews and say that Ashton Kutcher does a pretty good job at representing the personality found in Jobs’ speeches and in what has been written about Jobs — particularly in the massive authorized biography by Walter Isaacson.

One quote in that book, from one of Jobs’ old girlfriends, pretty much captures the character in the film: “He was an enlightened being who was cruel,” she told Isaacson. “That’s a strange combination.”

In anticipation of Sunday's festivities, Jimmy Fallon interviews Bruce Macabee, the puppy who predicted the Patriots to win. L.L. Bean celebrates it's 100th birthday in a fun way, Darren Aronofsky wants Russell Crowe to play his Noah, LeVar Burton gets the @ReadingRainbow twitter handle, Neil Young talks about Steve Jobs' love for vinyl, and an infograph on the social lives of religious Americans, and our favorite scenes from the classic 1993 film, Groundhog Day.

Kodak camera. Image via http://www.wylio.com/credits/Flickr/2992854214

Lately I’ve been thinking about why it’s important for an organization, be it religious or for-profit, to be more cannibalistic.

In the late 19th century, Kodak emerged as a trailblazing company that ultimately brought photography to the masses. An American-born business, the golden boxes of film became synonymous with family photos and even professional photography.

As a little guy, I had one of their Instamatic cameras, and I remember the eager anticipation of sending of the film and waiting the two weeks or so to get the results back.

Suffice it to say the landscape for film and imaging has changed radically in the meantime.

Now, practically every electronic device we carry has a still picture or video camera embedded in it. And for less than a thousand dollars, a photography enthusiast can buy a camera that not only shoots digital images that rival most professional film renderings; they also can shoot high definition movies and edit the videos on their laptop computers.

It may not surprise many that Kodak has suffered greatly at the hands of this digital revolution. The company has failed to post a profit in many years, and recently filed for bankruptcy.

All the hype about SOPA, dogs bark to the tune of Darth Vadar, debunking myths about homeschoolers, Tim Tebow visits Sin City, innovative musical projects, extreme skateboards, the day the LOLCats died and more.

Each day leading until Christmas we will post a different video rendition of the "Hallelujah Chorus" for your holiday enjoyment and edification.

Today's offering is a group effort that comes compliments of the clever folks at Pavone Advertising in Harrisburg, Penn., the even-more clever designers of the Melody Bell app for iPhone and iPad, and the cleverest of them all, the late great Steve Jobs (for it is he who blessed humanity with the iPhone in the first place.)

In its 2011 Holiday Greeting, Pavone employees perform Handel's timeless Christmas favorite — entirely using their iPhones, iPods and iPads.

Watch their epic peformance inside ...