tragedy

What could it possibly mean to us that an endangered species of orca whales hold a mourning period after losing their young? While mourning is a natural habit of many creatures, we should pay attention to Tahlequah’s process of grief. Perhaps if we observe the creatures we have been called to care for and learn from, we might learn something about what it means to be human.

O God,

this morning when we woke to your presence in and around us,

we also woke to a heavy world,

and in this world, we can’t make sense of all the things

that are wrong and should be made right.

IF THERE IS ONE CONFESSION a journalist never wants to make, it’s that she can’t handle the truth. Many of us got into the business for the express purpose of truth-telling, and for journalists growing up in the post-9/11 dawn of the 24-hour news cycle and the war in Iraq, the challenge to tell it boldly and well is our guiding star.

The nights are awfully cloudy these days.

When Syrian refugee children washed ashore in Libya in 2015, the images were indelible in their lonely, awful stillness—our decade’s “vulture and the little girl,” our “Falling Man.” Editorial rooms around the country debated whether splashing images of drowned babies across our platforms was truly in the public interest. Can pressing on exposed nerves yield anything but a howl?

Many outlets—including Sojourners—decided against publishing the photos. Everyone saw them on social media anyway.

The West Nickel Mines School is long gone. Two of the survivors are now married. Several of the couples who lost their daughters have had more children.

The shooting 10 years ago in [Bart Township, Pa.] made headlines across the world as the Amish rushed to forgive the shooter. But the grief and pain live on.

On Oct. 2, 2006, a heavily armed milk truck driver, Charles Carl Roberts IV, burst into the West Nickel Mines School shortly after recess. By the time Roberts had committed suicide, less than an hour later, five girls aged 6-13 were dead, and five others severely wounded.

Photo via iofoto / Shutterstock

Would we press harder if we thought of our words not as another voice in the fracas but as God’s mandate to justice? The word of the Lord hits Amos as one who is otherwise apt to mind his own business. Those who are compelled to speak should never stop speaking.

I’ve heard it said that you don’t know true love until you hold your baby for the first time. I hate that, for so many reasons. And I hate whoever has said it to me or anyone else. Hate it.

This may come as a shock, but I’ve got the slightest anger issue. It’s more accurate to say I didn’t know true anger until I became a mother.

There’s the daily anger, like slaving away in the kitchen for hours only to have people gag and demand crunchy toast and cookies to eat, while they scream and scratch their sister and slip on spilled water and cry for hours. There’s the hourly anger, like the struggle between wanting to check out and check e-mail in the face of little people wanting to play or needing to be disciplined.

THE KILLING OF 18-year-old Michael Brown in Ferguson, Mo., last year and the events that followed sparked protests by the community in the St. Louis area asserting that black lives matter and ignited a discussion on race relations in the United States.

On the heels of non-indictments in the slaying of Brown and other black men, our nation focused its attention on the drastic inconsistencies inherent in our judicial system. To many observers, black lives had less standing in our nation than white lives.

Rodney King, Trayvon Martin, Mike Brown, Eric Garner, Tamir Rice, Walter Scott, and the churchgoers in Charleston, S.C., are part of a long list of black victims of violence. They are victims of an American narrative that devalues black souls, black lives, black bodies, and black minds. In response to these tragic events, particularly since the non-indictment of the police officers who killed Brown and Garner, many evangelicals have been calling for a biblical practice that is often absent in American Christianity—the call to lament.

On one level I am thrilled that evangelicals are discovering the importance of lament in dealing with racial injustice. However, I am concerned that the way lament is being used by some white evangelicals is a watered-down, weak lament that is no lament at all.

Lament is not simply feeling bad that Brown won’t be able to go to college. Lament is not simply feeling sad that Garner’s kids no longer have a father. Lament is not asserting your right to confront the police because, as a white person, you won’t be treated in the same way that a black protester may be treated. Lament is not the passive acceptance of tragedy. Lament is not weakly assenting to the status quo. Lament is not simply the expression of sorrow in order to assuage feelings of guilt and the burden of responsibility.

The Rev. C.T. Vivian, who was central to the achievements of the civil rights movement of the 60s, said in an interview with me this week that the evil perpetrated at Emanuel AME Church in Charleston, S.C., was “the best thing that could have happened.”

Not the deaths of the innocent people, he says, but the evil act that was carried out in a house of worship made way for critical action that might not otherwise have happened. “It came out even better than anybody would have thought,” he said, “because we not only got the flag down, but more than that, we got rid of the great Southern symbols. If we handle it right, we have a good chance of getting a whole lot done more than we thought. Black ministers have to go to white ministers and say this is the day that we've been waiting for, the day when the public is really ready to have the war of yesterday forgotten.”

Vivian may well be right, but the incident made this writer wonder, yet again, about the whereabouts of God in the presence of oppression.

“God is in control.”

The statement comforts many people because deep down we know that we are not in control. We can do everything we can to protect ourselves and our families, but we know that despite our best efforts, tragedy can strike at any moment. And so it’s comforting to believe that if we aren’t in control, Someone else is.

But something inside of me recoils whenever I hear the phrase, “God is in control.” Many believe that God’s sovereignty means that God is behind everything that happens. But I find no comfort in that view of God. In fact, a God who micromanages and controls every event isn’t a God worthy of belief.

The world is swirling with issues.

Picking up my phone and opening my news app each morning is being met with more and more dread each day.

When something hits the news, it is fascinating to watch people jump onto social media and begin “yelling" out their answers for how to heal our broken systems.

Of course, there are almost always at least two completely different opinions for how these problems should be fixed, which typically leads to people drawing lines in the sand, picking their stance, and not budging. Relationships often fracture and a polarized a world gets more polarized, rendering it immobilized for the work of reconciliation.

Whether it’s on our Facebook page, Twitter feed, or around our table, I assume most of us can think of an interaction where this unhelpful and potentially destructive reality played out.

So, does this “yelling” of our opinions actually help heal the broken systems and the people whom those systems are breaking?

Andrew W.K. at the Village Voice received a question from someone whose brother was diagnosed with cancer. In his grief, he is frustrated by his grandma’s prayers and sees them as “superstitious nonsense.” Andrew’s brilliant response is a very worthwhile read, in which he positions prayer as a posture of humility, a deep realization of our smallness.

When senseless tragedy occurs, people of faith often rush to explain and control. As finite human beings, we are limited in our knowledge and power, which makes us uncomfortable. When we encounter something incomprehensible, we are driven to explain it. When a situation reels out of control, we long to control it. We invite God to fill those gaps of our discomfort, our lack of understanding and control.

We look for redemption stories, the ways God is bringing about good through a tragic situation. We do this to avoid letting the grief overwhelm us. Like grandma, we pray because we are hoping to claim some power in our helplessness. Our prayers end up being more beneficial for ourselves than the person we are actually praying for.

Unfortunately, what happens then is we cease to need God beyond the quick explanation. We’ve tidied up the situation with reverent prayers and spiritual meaning. We’ve quickly salvaged the ecosystem of our faith despite a tragic intrusive incident — our belief in the God of the gaps remain intact. Everything stays the same. When we do this, we are making God into an idol, one that explains and controls according to our sensibilities.

The television show Castle involves a mystery writer (Richard Castle) who helps a New York City homicide detective (Kate Beckett) solve tough cases. Beckett decided to become a police officer after her mother, a community activist, was murdered and the case was never solved.

In one episode, Castle notices that Beckett keeps a stick figure in the top drawer of her desk at the precinct. It’s odd-looking. The sticks that form the limbs don’t match exactly. The head looks like one of those football-shaped coin purses. It’s all held together by what appears to be seaweed and twine.

Castle wants to know the story behind it.

Beckett tells how on the day of her mother’s funeral, she was really sad so her father took her to Coney Island, one of her favorite places. They walked along the beach in their funeral clothes for a long time. It became a special time for the two of them.

At one point, they decided to gather items that had washed up on the beach and they made the stick figure.

So, why does she keep it in her drawer?

“He’s a reminder,“ Beckett says, “that even on the worst days, there is a possibility for joy.“

Like many of you, I’ve been overwhelmed and deeply saddened by the events that have transpired in Ferguson, Mo. And at times I’ve felt helpless, 350 miles away in Cincinnati, as friends of mine are in Ferguson praying, marching, organizing, and working for peace and justice.

In my conversations with friends of color, I have witnessed their pain and frustration and deep angst over the events of Ferguson. The past two weeks have hit very close to home for them.

With white friends, the response has been mixed, but the overwhelming sentiment is one I’ve already identified: helplessness. I am not satisfied with this response. I believe there are ways we can respond, bear witness, be in solidarity and work for justice in this moment. Our love for God and neighbor demands we engage. If you are like me, you are praying without ceasing for the Shalom, peace, and justice of God to reign in the hearts and minds and streets of Ferguson and throughout this nation and world. So how can we pair our prayers with constructive action?

Here are ten ways white Christians can respond to Ferguson.

One in four individuals will suffer with a mental health issue in a given year — and that these statistics can often be our friends, family, or ourselves. After tragedies like what happened in Isla Vista and on Seattle Pacific’s campus, we listen to the voices of victims’ families and mourn with them as they share stories of their lost loved ones. But we ignore an even more painful story about the lives of the gunmen.

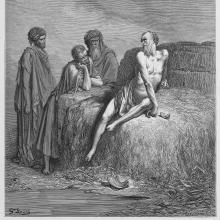

The world of Christian theology has seen its fair share of writings that address horrible suffering and the confusion about God’s character that it causes. The question has been on my mind in light of the Philippines’ calamity. Although satisfying answers are difficult to come by with a topic like this, I offer a few insights that have helped me to continue to trust God’s love. The biblical character of Job shows us how, as believers in a loving God, we should regard and respond to suffering around us.

It no longer surprises me when I hear people express cynicism and doubt about a caring God — I sometimes wonder why more Christians have not done so. Whose faith can remain undisturbed when Typhoon Haiyan kills 5,000 Filipinos and inflicts misery on thousands more? I recall a photo of a woman weeping by her child’s body inside a damaged church. Who can imagine her despair? Can we conceive of the hell endured in the same region by enslaved women and girls who are raped and degraded every day, every hour?

Twenty-first century readers of the Scriptures are likely uncomfortable with the book of Lamentations and its stories of weeping, groaning, and grieving. But, the act of lamenting is not unique to biblical Israelites.

Today’s world is full of lament-worthy situations. One need only turn on the nightly news to hear countless stories from places like Detroit, Michigan, and Camden, N.J. – plagued by record foreclosures, abandoned buildings, corrupt government officials, and boarded up businesses – to understand the devastating impact of high unemployment, increased crime, and precarious civic finances that have taken a toll on communities. Further, the country’s working poor earn wages that are so meager they have a hard time providing basic necessities for their families. Many cannot make ends meet without help from public assistance programs, which ultimately leads to feelings of despair and a decreased sense of self-worth

.

Modern readers also lament over the following.

Alexander was having a terrible, horrible, no good, very bad day.

It's a children's story. I know. A no good, very bad day ... how do you prepare your kids for that kind of day where nothing seems to go right, where at every turn knobs break and we step in puddles and get gum stuck in our hair?

Maybe, we tell ourselves, that we can move to Australia and everything will be better.

Well, no. Terrible, horrible, no good, very bad days happen there, too. They happen everywhere. Everywhere. It's a great book.

So what do we do about them? The classic children's book doesn't answer the question for us. Not really. It's just a little bit of truth telling with fun illustrations. Some days are just terrible, horrible, no good, very bad days.

But as we grow older, we learn that though these days do simply happen, that there are attitudes one can have, there are approaches to these days one can take.

One year after a gunman opened fire in a Sikh temple in Oak Creek, Wis., killing six worshippers, Sikhs say they are hopeful about the future and even more determined to be better understood.

“The legacy of Oak Creek is not one of bloodshed,” said Valarie Kaur, founding director of the interfaith group Groundswell, a project of Auburn Seminary in N.Y.

“[It’s of] how a community rose to bring people together to heal and to organize for lasting social change,” she told the PBS television program “Religion & Ethics NewsWeekly.”

IN THE PAST 150 years, the songs historically known as “Negro spirituals” have worn many costumes. They emerged, of course, from the Deep South during the days of slavery, when songs such as “Every Time I Feel the Spirit” or “Wade in the Water” were first sung by anonymous psalmists wielding hoes or pulling cotton sacks. Since that time they’ve been dressed in the style of the European art song, sung as grand opera, or even faithfully mimicked by well-meaning white folk singers.

The spirituals entered the mainstream of American culture through the performances of the Fisk Jubilee Singers from Fisk University in Nashville who, fresh out of slavery themselves, toured the North in the 1870s. In the 1950s and ’60s, the old standards were resurrected, and slightly rewritten, as marching songs for the African-American freedom movement and then echoed across the world as anthems for human rights from South Africa to Northern Ireland to Eastern Europe.

After all that, the spirituals can probably even survive being remade into “smooth jazz,” which is more or less what happens to them on Bobby McFerrin’s new album Spirityouall. Readers of a certain age might remember McFerrin as the guy who, in 1988, conquered the known pop music universe with an airheaded ditty called “Don’t Worry, Be Happy.” The tune was so infectious that it should have had a warning label from the Centers for Disease Control, but instead it dominated radio, won some Grammys, and, to McFerrin’s eternal horror, was used as theme music by the George H.W. Bush presidential campaign.

Photo via Sergieiev / Shutterstock

Memorial Day is a day to remember. A solemn holiday, it reminds us of the men and women who have died serving our country. Wreath-laying ceremonies and concerts fill the weekend, along with the placing of 250,000 American flags on the graves of Arlington National Cemetery.

Decorating graves is the oldest of Memorial Day traditions. In fact, the holiday was originally called Decoration Day and honored the soldiers who died during the Civil War. Flowers were placed on graves every year on May 30, and after World War I the holiday expanded to include soldiers who died in any war. In 1971, it was moved to the last Monday in May to create a three-day Memorial Day Weekend.

And that, writes Everett Salyer of HEAVEmedia, “is when all hell broke loose.” For many Americans, the holiday became a celebratory weekend filled with grilling meat, drinking beer, splashing in pools, and watching stock car races.