Walter Wink

STORIES ARE more than mere entertainment: They rest at the heart of who we are. They shape our understanding of the world and how we choose to live in it, both individually and collectively. They can sever us from one another or call us into deeper communion. This is the message at the center of two new books by Gareth Higgins (a Sojourners columnist) and Brian D. McLaren (a Sojourners contributing editor).

In The Seventh Story: Us, Them, and the End of Violence, Higgins and McLaren suggest that the violence and division that is part of our past and present are neither inevitable nor coincidental. They’re part and parcel of the stories we live by. The authors highlight six story types that are particularly pernicious and all too common: stories of domination, revenge, escapist isolationism, scapegoating, acquisition, and victimization.

Drawing on what theologian Walter Wink calls “the myth of redemptive violence,” Higgins looks at the role these story types play in justifying and perpetuating violence. He reminds us that, as was the case in his native Ireland, it is the work of peace and reconciliation—not more violence—that is truly redemptive.

Christians believe that Jesus definitively defeated the forces of evil. For Christians, faith is trusting that the way to defeat evil is the same way that Jesus defeated evil on the cross and in the resurrection. Jesus was no Jedi. He didn’t use “good violence” to protect himself or others from the evil forces that converged against him. Nor did he run from evil. Rather, he defeated evil by entering into it, forgiving it on the cross, and offering peace to it in the resurrection.

Of course, many – even those who profess to follow him – think Jesus is absolutely crazy. As the apostle Paul wrote, “We proclaim Christ crucified, a stumbling block to Jews and foolishness to Gentiles.” It’s true that following Jesus by responding to evil with nonviolent love is risky. After all, Christ was killed, as were his disciples. But fighting violence with violence is also risky and only perpetuates a mimetic cycle of violence.

Denominations proliferate in Korea, Rev. Lee said, because church leaders have failed to die to themselves. People are concerned about recognition and their reputation, taking the glory for themselves, instead of for God. And Rev. Lee identified income inequality in South Korea as one of its greatest problems. Again, it calls for dying to the idol of wealth, and putting God’s love, along with serving one another, at the center.

The expected ecumenical agenda of economic justice, peace, protection of God’s creation came before the Jeju Forum in clear and forceful ways. Agnes Abuom, from Kenya, who is Moderator of the WCC Central Committee, said we are slaves to the larger economic and political systems; that’s another way in which we have to die to ourselves, echoing words from the Rev. Lee’s sermon.

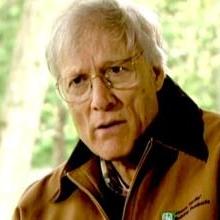

WALTER WINK IS known as a lectionary commentator with lucid biblical insight, a chronicler of nonviolent practice, a scholarly essayist, an arrestee in direct action, and one of the most important theologians of the millennium’s turn. He effectively named “the domination system” and its collusive principalities, opened up biblical interpretation to an integrated worldview, and brought the New Testament language of power back on the map of Christian social ethics.

Two years ago he crossed over to God, joining the ancestors and saints. His first two posthumous books have now appeared. They make for good companion volumes. Let me weave back and forth between the two. Walter Wink: Collected Readings is the anthology of his core work. Just Jesus: My Struggle to Become Human is a short autobiography. The second is the more remarkable—because it’s so rare that a world-class scripture scholar should tell his or her own story in relation to encounters with the biblical witness. And all the more so because it was a project undertaken after he was diagnosed with Lewy body dementia.

Given the dementia, the book itself is an effort of his “struggle to become human.” An early version of the manuscript included oral history and other sources narratively adapted to a first-person voice, but in the end his partner in all things, June Keener Wink, pressed for it to be pure Walter. No words not his own. His voice is easily recognized in these pages, though not always in the familiar crafted and noted style, rich in quotable one-liners. The jewels are here all right, but this text feels simpler, sparer, plainer. There are prayers and memories of one suffering the weight and creep of memory loss. Though it is a book he conceived and set to writing, June (aided by a sainted editor) lovingly completed the sculpture with autobiographical pieces, journal entries, prayers, dreams, and important portions of his final magisterial work, The Human Being: Jesus and the Enigma of the Son of the Man. The latter, also well represented in Collected Readings, frames the struggle (Jesus’, Walter’s, and our own) to become human.

I’ve always had a curious sort of sympathy for the bad guys. I cried when King Kong died. I wept at Darth Vader’s demise. And I felt like the whole melting thing was a little bit harsh for the Wicked Witch of the West.

Maybe they didn’t really want to be bad. Maybe they were just written that way. Could be that they had a rough childhood, or people made fun of them for being green, or big and hairy, or breathing through a big, black mask. I mean, imagine that on the playground …

Ever since my childhood I’ve felt more comfortable in darkness than most kids seemed to as well. My 10-year-old son won’t even go into any unlit room in our house without being accompanied by our dog, Maggie. But I actually enjoyed being in the dark. It seemed like the one place where I could let the otherwise literal, concrete parts of my brain take a rest, and allow my imagination to run wild.

Theologically, we’re taught to hate, or at least fear, the darkness. We are children of light, God called light into being, and it was from this light that all things were formed. So what use do we have for darkness?

What a relief it would be to dwell in [faith] communities where we acknowledge our shadows in a healthy acceptance of ourselves as containers of all the opposites! It may prove beneficial to be forced to face, daily, the humiliating fact that some of us are no less violent than those whose policies we oppose.

—Walter Wink, Engaging the Powers

I AM A conscientious objector, and I am drawn to violence. My attraction to violence is both innate and learned. When something frightens me, my hands clench into fists. When something angers me, I want to inflict pain upon that thing. But a person cannot inflict pain upon a thing, so I seek out those whom I deem responsible for said thing and my desire to inflict pain upon a thing morphs into a desire to do violence to another person. Since I was a child, I have fantasized about using violence to stop what I see as bad and thereby become good.

It is from this point—from these fantasies of righteous violence—that I begin this essay on my journey to principled nonviolence and conscientious objection. This is a story of change and choice, but it is not a story of transformation: I am who I have always been.

In fall 2012, I spent three weeks in Israeli military prison for refusing to enlist in the Israel Defense Forces. (Every Israeli citizen, except for the ultra-Orthodox and Palestinian citizens of Israel, must serve in the military.) My sentence was brief, but the process that brought me to the prison’s gates took almost a decade.

"The arc of the moral universe is long but it bends towards justice," proclaimed the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

It may bend towards justice, but it does not bend gently. It bends behind sweat of the brow, creativity of the mind, and love from the soul of those who believe that every living soul not only desires justice and equality, but has a right to it. You see, justice is not a passive pursuit. The moral arc will not bend without encouragement.

Dr. King was a living example of the kind of person who encourages the moral arc of history to bend toward justice. He is also an example of the only effective way to bend that arc — non-violently. We cannot hope to bring about justice by unjust means. Might, physical confrontation, and other forms of domination will ultimately only result in nurturing an understanding that domination is an ineffective way to resolve issues of justice — and domination is the exact opposite of justice. As King says, "Hate begets hate; violence begets violence; toughness begets a greater toughness. We must meet the forces of hate with the power of love."

As we attended workshops and concerts, met new people, and tried to make sense of the larger impact this gathering might have beyond us, we kept coming back to that statement we heard early on about Walter Wink. What is Christian imagination? How do we imagine Christianity? Whatever it means, imagining Christianity is exactly what happened at Wild Goose.

Here's an example: Throughout the weekend, Fullsteam, a craft brewery in nearby Durham owned by an alumnus of Wheaton College (yes, that Wheaton) sold selling beer to quench the thirst of Goosers during late night sessions and performances (a la Homebrewed Christianity, etc.). And on Saturday afternoon — call it an early evening happy hour — a group of rag-tag musicians, armed with a few folk instruments, a trumpet and percussion, led a jolly crowd of more than 100 in Sunday School choruses and old-timey spirituals. They called it, “Beer and Hymns."

There, caught up in a holy wind of hops and hope, we reimagined what church might be during an ad hoc version of “He’s got the Whole World in His Hands.” We the motley worshippers alternated “He’s got the whole world” with “She’s got the whole world,” proudly singing at the top of our lungs, “She’s got the liberals and conservatives / the gays and straights / and a big ole mug of beer/ in her hands.”

Walter Wink, 76, a world-class biblical scholar and non-violent practitioner, crossed over to God on May 10 at his home in Western Massachusetts. Following a slow decline, he had been in hospice for several weeks in the company of his beloved June and their family. (See "Confronting the Powers," Sojourners December 2010)

As a first year seminarian in New York City, more than 35 years ago, I was fortunate to have Walter as my New Testament instructor. In a seminar session on the "pearl of great price" in Matthew, I have a vivid memory of him breaking the discussion so we could go round the circle and each reply to the question: "For what would you be willing to die?" I don't so much recall my own halting answer, as the depth of the question he understood was put to us by the text. It's since become my conviction that no one should escape seminary (or baptismal preparation for that matter) without facing with that query.

Which is to say he was himself an engaged scholar, connecting the academy with the risk of the streets. While filling his first teaching post at Union Seminary in New York he was simultaneously serving on the national steering committee of Clergy and Laity Concerned about the War in Vietnam (1967-76).

He was notorious for foundation-shaking works. When I met him, Walter was a rising star in the biblical guild, on the fast track at Union. Then he published a little polemical book called The Bible in Human Transformation (1973) which made bold to declare, “Historical biblical criticism is bankrupt." It assailed the myth of scientific objectivity, the disembodied approach which kept the text at arms length and pre-empted commitment. In many respects it anticipated the contextualizing hermeneutics of feminist and liberation readings, but it didn't win him friends in the academic guild.