White Privilege

Questions to help you use your privilege for the flourishing of all.

To my acquaintance, and white people who need to hear it, I say this lovingly and from a place of abundance, without scarcity: I know you are hurting too. You are human. But this is not about your pain.

RIAN JOHNSON'S FILM Knives Out wastes no time setting up the murder mystery that powers its plot. In the very first scene, famed mystery writer Harlan Thrombey (Christopher Plummer) is found in the library of his mansion, his throat cut. Harlan’s family is shocked. His Latina caretaker, Marta (Ana de Armas), Harlan’s closest confidant, is devastated. The police think it’s a suicide. Private detective Benoit Blanc (Daniel Craig) thinks otherwise.

The mystery of Harlan’s death may be the plot of Knives Out, but as the story progresses, it’s clear that the film is actually about something else.

Bootstrapping—the idea that one can achieve success purely through hard work and determination—is touted in most areas of public life, from business to education to politics. White Americans particularly love to claim that we’ve risen from tough circumstances while making it harder for less-advantaged populations to do just that.

In Knives Out, the bootstrapping myth is everywhere. Harlan’s children are proud that their dad built a publishing empire. Harlan’s daughter Linda (Jamie Lee Curtis) tells Blanc that she, too, created her own business from the ground up. But, of course, those stories aren’t the whole truth. Linda would be nowhere without the hefty loan she got from her father. Harlan himself may have worked hard for his success, but as a white man, there’s no doubt his path was easier than it would have been for others.

WHITE EURO-AMERICAN Christianity is dying, according to Miguel A. De La Torre, and from his point of view, its death is necessary. It has distorted the gospel with Euro-American nationalist ideals that benefit white communities at the expense of communities of color—heretical beliefs grounded in fear and exclusion, rather than love. In Burying White Privilege: Resurrecting a Badass Christianity, De La Torre deconstructs Donald Trump’s abundant evangelical support. In doing so, he offers guidance on how Christians can move forward.

Whiteness lies, he explains. It lies about the superiority of particular beliefs and nations. And this superiority complex has led to a lot of violence being done under the name of Christianity, including displacement, slavery, and genocide.

SOME TIME ago I took a long walk with a favorite professor of mine from the University of Illinois. I talked about how I’d turned my undergraduate activism in the campus diversity movement into a full-time career, and he told me an interesting story about identity.

The week before, he had needed to shift his 9 a.m. class to 8 a.m. because of a mid-morning appointment. He promised his students he’d bring in Panera to make up for dragging them out of bed so early. One of his students, a white kid from a rural area in Illinois, had asked, “What’s Panera?”

Everybody else in his highly diverse class knew what Panera was, he stated matter-of-factly, making that white student’s distinctive experience all the more striking. “Shouldn’t any campus diversity movement that takes identity seriously be open to her uniqueness?” he asked me.

I stifled a laugh and turned the conversation to another dimension of identity, one that I felt really mattered. Surely my professor friend knew that the assigned role of white people in campus diversity programs is to listen to the bigotry that people of color have experienced and apologize for the ways they have benefited from racist systems. The only time they are allowed to speak proactively is if they occupy one of the other “preferred” identities—if they are gay, or female, or have recently converted to a minority religion.

In the weeks since Donald Trump was elected president—in between being scared out of my mind about the violent attacks on ethnic and religious minorities in America (my kids’ names are Zayd and Khalil)—I’ve thought about that rural white student. The place she’s from voted overwhelmingly for Trump. I wonder if she did. I wonder why I never wondered much about her before.

BY ABOUT SIXTH grade, a set of kids in the professional middle-class suburb where I grew up stopped doing homework, or really much work at all. They’d goof around in everything from math class to gym period. Getting average grades or being sent to the principal’s office for misbehavior didn’t seem to bother them that much. And their parents seemed to greet it all with a shrug.

It looked like good fun to me, so I figured I’d give this not-giving-a-damn thing a try. My parents greeted my Bart Simpson attitude with something stronger than a shrug.

I remember their fury after a school meeting where the teacher must have explained that my grades had fallen because I spent class time chatting with friends rather than focusing on worksheets. Right before the hammer came down, I attempted a weak protest: “But none of the other kids are doing work in class either,” and ticked off a set of names that my parents knew.

“You are not like them,” came the stern response.

This confused me. I thought I was like them. I played sports and video games, watched MTV and worshipped skateboarder Tony Hawk, just like all the other 12-year-old boys.

“If you are not head-and-shoulders above the next candidate in a hiring process,” my mother sternly said, “they will not give you the job.” She repeated: “You are not like them.”

It is a scary thing to let the ones who have been at the bottom rise to the top.

It’s scary when privilege begins to lose.

It’s scary when those that have been “other” for so long get a place at the table.

It’s scary when things get uncomfortable and messy.

But then, that’s Kingdom.

If we have learned anything from the past several decades, healing from a 500-year heritage of slavery will take more than a generation or two. I am humbled when I think of this because I realize that the relentless, demonic agony inflicted for 500 years will not be undone or healed by a single generation. My body will have flitted through the breeze as dust many times over once this 500-year heritage has been unwound and restitched. Healing takes more than just time.

Veora Layton-Robinson, a student in her final year at New York Theological Seminary, had signed up for a full load of courses when she decided to add one more: a class on Black Lives Matter.

The minister and elementary school teacher was inspired by the class to start developing a Black Lives Matter chapter with members of her Mount Vernon, N.Y., church and community, convinced that more needed to be done to address police brutality, address concerns about violent crime and help people understand the power of voting.

Trump’s comments about women and sexual assault, Muslims, minorities, etc., are difficult to hear because they’re coming from a man running for president — but also because it forces us to confront our own worst tendencies. Trump is able to do and say these things with little or no consequence because of his privilege as a wealthy, white man. And before you think he’s different from you, before you distance yourself from his actions, consider your own privilege and how you’ve used it to say and do things that are insensitive and inappropriate.

lastbackup / Shutterstock

A COUPLE OF YEARS AGO, while doing research on social privilege for an introductory ministry course, I came across an article titled “White Fragility.” Even a skim of the first few pages was enough to pique my excitement. In it, author Robin DiAngelo—an expert in multicultural education—describes in sociological detail a common set of defensive and destructive responses that people have when facing the reality of their own privilege.

I recognized each response she described from those my students had whenever I asked them simply to face—let alone begin to dismantle—the various forms of social privilege they each embody. Where, I began to wonder, could I squeeze this article into an already over-packed course syllabus? How could it best help us navigate the difficult issues we were trying to engage?

Emptying ourselves

Social privilege is a daunting topic to engage. When teaching it, I draw heavily on Peggy McIntosh’s now famous definition of its racial manifestation:

I have come to see white privilege as an invisible package of unearned assets that I can count on cashing in each day, but about which I was ‘meant’ to remain oblivious. White privilege is like an invisible weightless knapsack of special provisions, assurances, tools, maps, guides, codebooks, passports, visas, clothes, compass, emergency gear, and blank checks.

What McIntosh helps us see is that social patterns of privilege are maintained because people carry them about and use them while, at the same time, people are able to carry about and use their privilege because those social patterns are maintained. The effect is cyclical, and it happens without any of us being particularly aware of our own complicity in the system.

Society confers unearned gifts on people who embody particular privileged traits—straight, white, able-bodied, middle-class men, for example—while neglecting to confer them on others. This isn’t to say that people who embody more privilege are explicitly homophobic, racist, ableist, classist, or sexist. It doesn’t mean they don’t work hard for the goods they accumulate in life—of course, many do. It’s just that it feels perfectly natural to walk through an open door without ever noticing how it swings shut in the face of the equally hardworking genderqueer Latinx whose wheelchair wouldn’t even fit.

Former Stanford swimmer Brock Turner made headlines when he received a six month prison sentence for raping an unconscious woman behind a dumpster. Turns out, he will only serve half of his already very short sentence, reports Mic.

A document on the Santa Clara County Department of Corrections lists his release date as Sept. 2, 2016.

Image via Photo courtesy of REUTERS/Jim Bourg/RNS

A year ago, when the death of Freddie Gray and resulting unrest in Baltimore filled the news, the Rev. Kathy Dwyer felt she had to do something.

“Every time I turned on the TV, I just felt like I was getting punched in the gut from watching the issue of racism just escalate in our country,” said the white pastor of a predominantly white United Church of Christ congregation in Arlington, Va.

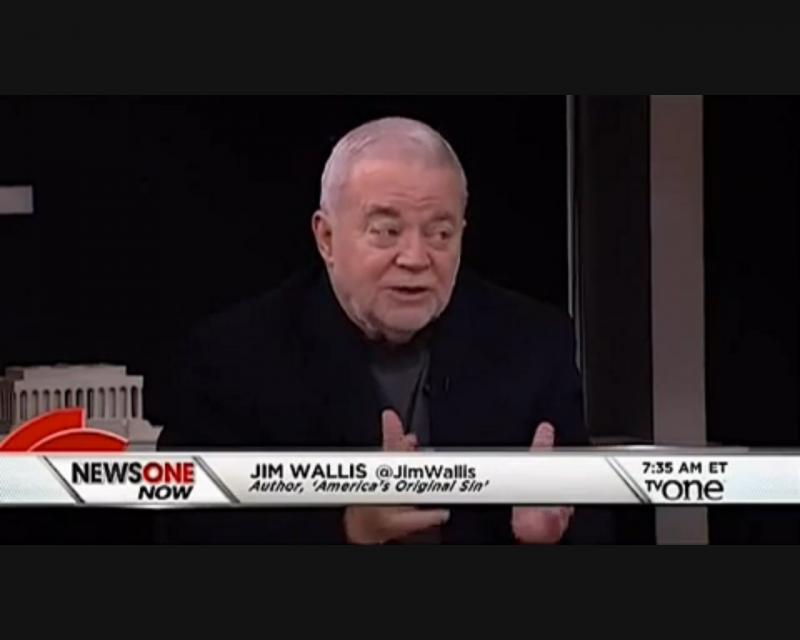

Jim Wallis, social activist, author and one of America’s most influential Christian voices discusses social justice and the Christian life.

Listen to the interview here.

Outspoken evangelical preacher Jim Wallis has been arrested many times at civil rights and anti-war protests over the years. In the wake of the deaths of Michael Brown, Eric Garner and Tamir Rice, he tells Andrew West it's time for America to confront its 'original sin'—racism.

We must resist the terrible teachings of Donald Trump

This week, as Christians mark the crucifixion and resurrection of Jesus, we find ourselves traveling from the darkness of Good Friday into the light and joy of Easter Sunday.

Here’s my review of “America’s Original Sin: Racism, White Privilege, and the Bridge to a New America,” a new book by Jim Wallis: If you are a Christian, you should read this book.

Wallis, founder of Sojourners, a national faith-based organization that advocates for social justice, is a public theologian and the best-selling author of 12 books. He is white.

Rather than summarize his latest book, I am sharing some of my favorite passages. In Wallis’ own words: