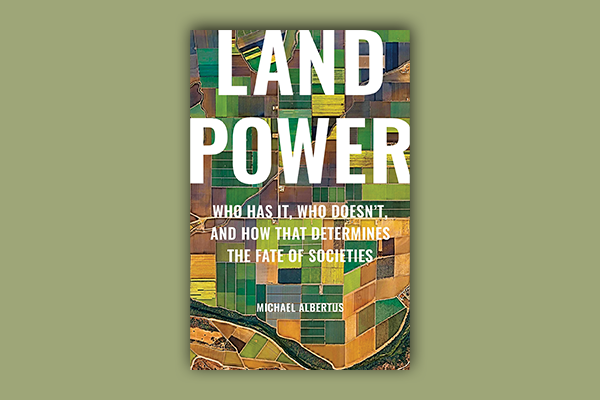

MICHAEL ALBERTUS’ THESIS is both simple and grand: “Land is power.” From the earliest settlements of Mesopotamia to the land reforms of Communist China, Albertus insists that control of land has played a central role in intensifying economic disenfranchisement, ecological destruction, and racial and gender inequality. Too often, a minority has centralized land to plunder for resources, no matter the cost.

No utopian impulse for reform has yet freed itself from replicating the inequalities its adherents sought to overcome. Reform often made things worse.

In Land Power, Albertus, a professor of political science at the University of Chicago, calls the past two centuries of large social redistributions of land the “Great Reshuffle.” These transformations, which continue today, have taken various forms. “Settler reforms” dispossessed Indigenous peoples in the Americas, Australia, and Africa. Revolutionary reforms in Russia brought collective ownership of large estates. The U.S. explored legislative policies that placed smaller amounts of land in the hands of single farmers, encouraging “land-to-the-tiller” reforms in countries such as Japan, especially after World War II. Countries including Peru experimented with land cooperatives.

No utopian impulse for reform has yet freed itself from replicating the inequalities its adherents sought to overcome. Reform often made things worse. Albertus tells the story of the Agua Caliente band of California, an Indigenous people whose land was ripped away by both colonization and the U.S. government’s “Indian Removal” policies and reservation system. In 1980, the Agua Caliente band faced another attempt at settler dispossession. After a wildfire burned through the band’s reservation, the government of nearby Palm Springs used this as an excuse to clear that land for a road to connect the city to a highway. The local Indigenous community fought back, but the city still built the road through ancestral burial grounds. This is one of many chapters in “the story of how land reallocation put white settlers and entrepreneurs at the top,” writes Albertus.

But he also believes that the power of land can be routed in a better direction. Albertus tells the story of Bolivian Quechua activist Silvia Lazarte and the women’s activist group Bartolina Sisa. Members of the Movement Toward Socialism coalition, Lazarte and the Bartolinas helped craft gender-conscious land reform policies, making land titles more accessible to women. Over the past three decades, Albertus writes, 46% of land titles are now being granted to women.

Land Power gestures at the role that religion played in shaping land reform policies through Manifest Destiny, the belief in the providence of American imperial expansion. While this settler legacy to Christianity ought not be forgotten, there are other ways of conceiving of religion’s relationship to land reform. For Christians wanting to learn how theology can inspire justice-oriented land reform, I recommend reading Ownership: Early Christian Teaching (1983), in which the Filipino activist Charles Avila argues that much of early Christian teaching was unequivocally committed to an egalitarian vision of cooperative land ownership. In naming land as the “birthright” of all God’s children, he issued a prophetic critique of the feudal land policies that plagued Philippine society in his own time.

There is no denying that “land is power.” But activists like Avila remind us that land is also a gift from God, one meant to be shared.

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!