Even before ballots were cast in the 2020 presidential election, many were suspicious of how the Trump White House would handle a potential transfer of power. As the election wound down with clear margins in President-elect Joe Biden’s favor — and as Donald Trump continued his refusal to concede — more people began to use the word “coup.”

Coup d’etat is defined as the “sudden, violent overthrow of an existing government by a small group,” necessitating control of armed forces, whether the military or police. Another term being thrown around is “self-coup,” or autogolpe in Spanish, in which a leader dissolves or otherwise destabilizes existing checks and balances within the government. This is often traced back to the 1992 dissolution of Peru’s Congress and judicial branch by then-President Alberto Fujimori, with the support of the military.

So does Trump’s refusal to concede or his efforts to interfere with election certifications signal an attempted “coup”?

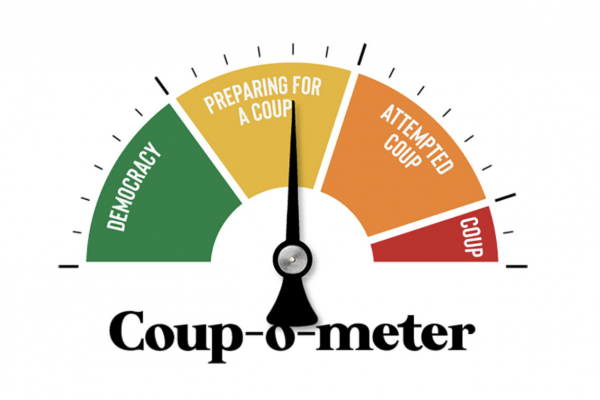

To answer that question, many have been pointing to the Coup-o-meter, housed at isthisacoup.com.

Created by Nick Jehlen and Jethro Heiko, longtime creative partners who design tools supporting progressive movements, the Coup-o-meter is currently firmly in the yellow zone: “preparing for a coup.” (You might recognize the pair’s pins from another project, Dissent & Co., a popular depiction of the late Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s “dissent collar,” which she wore on days she dissented on Supreme Court opinions.)

For Jehlen and Heiko, it was important to provide information on a coup before one could happen.

“In general, in this country, there is an assumption that our democratic systems are rock solid,” Jehlen told Sojourners. “Rather than wait until a coup actually was unfolding, we tried to stay out in front of it, and put together some information that was simple and clear, and could help people determine whether a coup was actually in progress.”

Heiko and Jehlen coordinated with Choose Democracy, whose stated mission is to prepare Americans for the possibility of — and resistance toward — a coup. In their initial research, Heiko and Jehlen turned to The Anti-Coup by Gene Sharp and Bruce Jenkins, a resource freely available through the International Center on Nonviolent Conflict, as well as research on civil resistance against coups from Stephen Zunes, professor of politics and international studies at the University of San Francisco. They attempted to pull together, said Jehlen, “a set of triggers that we think would signify that it was actually in progress.”

“One of the things that's really important in [this] work is to be calm, and stay vigilant, and [observe] what's happening, but not to be overly reactive of every single thing that happens,” Heiko said. “Trump, and potentially his followers, would love everyone to be highly reactive to what they're doing all the time, to get people more agitated, to take advantage of threats of violence or actual violence, in order to then escalate to the next step of a coup attempt.”

To ground the situation, Heiko says he returns to these questions:

- What's actually happening? Is it just words, or are there actions behind it?

- Are people actually responding?

- Does Trump have collaborators?

- Is there something actually changing about the election results?

“A coup is a specific tactic that requires a specific kind of response. We don't think that this is a coup right now,” Jehlen said “... at this time, we just don't see a path to seizing power through the actions that are being taken, which means that we should be doing something else besides defending against a coup.”

Barbara Wejnert, professor of global gender and sexuality studies at SUNY Buffalo and an expert on democratic transitions, is still concerned about a coup, seeded by Trump’s four years of strategic judicial placements and installation of Attorney General Bill Barr. (Remember, in the example of Peru’s 1992 autogolpe, it involved wresting power from their judicial system.)

“In the American situation, it really is not military per se ... but we have the paramilitary groups that are on the rise,” Wejnert said. “And, of course, everybody has weapons. They're not fighting with knives. They are sometimes more heavily armed than police forces.”

Wejnert draws comparisons to Adolf Hitler’s development of Nazi party military groups and armed units to Trump’s modern-day armed supporters, pointing to his condoning of armed participants in the 2017 Unite the Right Rally in Charlottesville, Va.

“Disinheriting the rule of law and allowing the white supremacy of the paramilitary groups to rise to power, that's how Hitler actually eventually became so powerful that the regular politicians were afraid of him — and tried to incorporate him [into governance] to somehow smooth it out, which of course didn't work because he took power completely then,” Wejnert said.

To an extent, Jehlen sees this perspective. “I think President Trump and his allies did their best to create a situation where violence in the streets in support of a coup was possible,” he said, pointing to attempts of violence at ballot-count locations and threats against election officials.

But he emphasizes that threats of violence are not equal to acts of violence.

“One way to think about this is to look at the threats,” Jehlen said. “The other way to think about it, is to look at all of those thousands and thousands of people who, during a pandemic, are showing up for work, and doing what is frankly an extraordinarily boring job, in order for us to have a working democracy.”

In the coming months, Wejnert said she is keeping an eye on Republican governors, senators, secretaries of state, and other state-level power players to resist Trump’s attempts at delegitimizing the election. Both Wejnert and Jehlen specifically mentioned the impact that the Georgia senate runoffs may have on solidifying belief in our electoral system, or further sowing doubt.

In the meantime, the Coup-o-meter will stay live. “The things that are underneath the reason why it's even a cause of concern right now aren't going away without a lot of work,” Heiko said. “We'll be back here again, and the next time someone might be better at building momentum, getting collaborators.”

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!