Magazine

JESUIT SPIRITUALITY revolves around the task of finding God in all things, reflecting on the meaning of the actions and events around us, and acting in the world as “people for others.” Those principles, in many ways, speak to the vocation of Sojourners—we don’t just cover news, we seek to understand how God is working in the world.

DC_Aperture / Shutterstock

IN OCTOBER 2014, at the age of 35, Ingrid Olson stood before her church of many years. “I am loved,” she told the 80 or so members of her congregation seated in the sanctuary on that Sunday evening. “I am God’s child. I am accepted—completely.” Olson listed other parts of her identity: her curiosity, athleticism, passion for music, Swedish heritage, her tendency to be passive-aggressive. “I am a sister, a daughter, a niece, a granddaughter, a friend,” she continued. Then she added something most people in the church didn’t know: “I am a Christian, lesbian woman.”

Olson is a lifelong member of the Evangelical Covenant Church (ECC), a denomination with Swedish-Pietist roots and 850 congregations in North America. Though the central identity of ECC churches is found in six “affirmations,” including the authority of scripture, the importance of missions, and the experience of personal rebirth, the ECC is not what’s known as an “affirming” church—one that encourages LGBTQ members to participate in the full life of the congregation, including marriage, church leadership, and ordination. Delegates at the 2004 ECC annual meeting voted to make binding a resolution that asserts the “biblically rooted” position on human sexuality is “heterosexual marriage, faithfulness within marriage, abstinence outside of marriage.” While the ECC might not say that being gay is a sin, it would certainly say that pursuing a same-sex relationship is out of the question.

Julia de la Cruz, originally from Mexico, is a farmworker, an organizer, and a member of the Coalition of Immokalee Workers (CIW). After forging agreements with 14 of the largest food retailers in the U.S.—including Walmart, McDonald’s, Trader Joe’s, and Chipotle—to establish labor standards and fair wages for tomato workers, CIW launched the Fair Food Program, a partnership among growers, farm workers, and retail food companies ensuring fair pay and humane working conditions on participating farms. This interview was conducted in English and Spanish, with Elena Stein, a faith organizer for Alliance for Fair Food, translating.

1. Why have farm workers in the U.S. continually faced unfair wages and inhumane working conditions? The body that was most responsible was not the growers who employ us, but actually the corporations at the very top of the supply chain who use their enormous purchasing power to demand artificially low costs of the produce we harvest. That demand results in growers cutting costs in the one place where they can: labor. And there you get the poverty and exploitation that we have experienced for decades.

2. Does it help farm workers if consumers stop purchasing products that are grown in bad working conditions? More and more we hear this idea of voting with your fork: this idea that consumers affect conditions based on how they use their dollar. But the truth is that if somebody chooses to refrain from buying a good, the impact really won’t be felt by corporations such that they’ll be forced to change their policies. But corporations will be impacted and forced to change their policies when a worker-led campaign forces them.

So we’d ask consumers to build consciousness by listening to farm workers and their experience and their analysis of the food system that nourishes each of us. The second thing we’d ask for is commitment—and that can mean a lot of things, but it definitely means getting to the street and protesting the corporations that have turned a blind eye to the abuses they have perpetuated.

TO ENTER la fortaleza where Jhonny Rivas was being held prisoner, I had to hand over my passport and undergo a thorough search, which included squatting naked on top of a mirror laid on the floor. I wanted to turn around indignantly and go home. Instead I faced the two female guards, girls really, one with braces, the other with the acne of a teenager. Por favor, I appealed. They exchanged an unsure glance, no doubt worried about el capitán strutting outside, then gestured for me to put my clothes back on. At the door, I embraced them.

Blessed are those who don’t follow unrighteous rules, for they shall be hugged.

I confess that I often practice my own beatitudes lite. It’s where I often want to stop, at the easier, feel-good variety of activism. But the beatitudes are as morally rigorous as those daunting Ten Commandments, albeit working through positive reinforcement—blessings rather than “thou shalt nots.” If you truly embrace them, they keep pulling you further and further out of the comfort zone of the self that always wants to stop at having done its part.

IF YOU'RE A Christian who cares about social justice, you can’t afford to ignore Texas.

In his book Rough Country, Princeton sociologist Robert Wuthnow puts it bluntly: “Texas is America’s most powerful Bible-Belt state.” Texas has the second largest population in the country, home to more than 26 million people. In 2014, Texans led six out of 21 congressional committees. And more than half of Texans attend church at least twice monthly.

No other state has more evangelical Christians than Texas. Many national Christian media companies, parachurch ministries, and influential megachurches are based in Texas. That’s why Texas is called the Buckle of the Bible Belt: It’s the most populous, wealthy, and politically powerful part of the country where evangelical churchgoing is still a dominant force.

But what if we reimagine the Bible Belt? In 2005, Texas officially became a “majority-minority” state, where traditional minority racial or ethnic groups represent more than half of the population. A majority of Texans under 40 in the pews are people of color. This creates an opportunity: Demographic change could lead to cultural change. What if we cast a new vision for faith in Texas public life that puts working families and people of color at the center?

But demographic change will not translate automatically into cultural change. The dominant historical Bible Belt narrative has influenced and shaped the identities of all Texas Christians, including in the African-American and Latino faith communities.

AS CHRISTIANS concerned about peace and justice, this time of crisis in the Middle East provides us an opportunity to return to our principles, the “springs of living waters” for people of faith:

- We need to oppose both anti-Semitism as well as any form of discrimination and racism against Palestinian Arabs. Solutions that promote or tolerate discriminatory and racist institutions and practices should be forthrightly condemned. Settlements, illegal under international law and discriminatory against Palestinians, need to be rejected rather than tolerated and legitimized.

- We need to work for justice, which requires that we work for a solution that levels the playing field rather than seek a “realistic” approach that reflects the balance of power between the parties, necessarily favoring the strong against the weak.

- We need to seek reconciliation and peace between the parties, rather than assuming eternal hostility and enmity between the parties.

“HAVE YOU BEEN born again?” The image of a second birth to illustrate conversion is often used by fundamentalist and conservative evangelical Christians. Yet in my experience such folks also tend to resist thinking of God as other than male. How can they overlook this very maternal activity of God’s Spirit?

Even Nicodemus gets it, at least at the physical level. In John 3, this high-ranking Jewish leader privately approaches Jesus to ask him where his charism comes from. In most familiar translations of the New Testament (such as King James and NIV), Jesus tells Nicodemus that he would understand if he were “born again” (3:3). But the Greek word anōthen is deliberately ambiguous. Jesus’ intended meaning is “born from above” (NRSV). “That which is born of the Spirit is spirit,” says Jesus in verse 6. The Holy One is our birthing mother.

When the literal-minded Nicodemus asks how a person can go back into his mother’s womb and be born again, we cannot be sure (in 3:9-10) whether Jesus gently chides or sarcastically puts him down: “Are you a teacher of Israel, and yet you do not understand these things?”

Sadly, many “teachers” throughout Christian history have not understood these things. It is now 50 years since Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique opened the floodgates of second-wave feminist cultural analysis, thus preparing the ground for biblical scholars and theologians such as Letty Russell, Rosemary Radford Ruether, Elizabeth Schüssler Fiorenza, and many more. Some of us began to see that orthodox, “objective” methods of interpretation were instead often subjectively male-oriented. We began to ask, “Where is the feminine in our sacred texts? Were women there?”

I see five ways in which the gospel of John deconstructs, or at least unsettles, the rigid patterns of patriarchy in the family and society in which Jesus lived. The roles Jesus played during his life and ministry were so atypical that they color this entire narrative.

Gumpanat / Shutterstock

WHEN I FIRST began to write this article, I thought to myself, "How do you promote something as vaporous as silence? It will be like a poem about air!" But finally I began to trust my limited experience, which is all that any of us have anyway.

I do know that my best writings and teachings have not come from thinking but, as Malcolm Gladwell writes in Blink, much more from not thinking. Only then does an idea clarify and deepen for me. Yes, I need to think and study beforehand, and afterward try to formulate my thoughts. But my best teachings by far have come in and through moments of interior silence—and in the "non-thinking" of actively giving a sermon or presentation.

Aldous Huxley described it perfectly for me in a lecture he gave in 1955 titled "Who Are We?" There he said, "I think we have to prepare the mind in one way or another to accept the great uprush or downrush, whichever you like to call it, of the greater non-self." That precise language might be off-putting to some, but it is a quite accurate way to describe the very common experience of inspiration and guidance.

All grace comes precisely from nowhere—from silence and emptiness, if you prefer—which is what makes it grace. It is both not-you and much greater than you at the same time, which is probably why believers chose both inner fountains (John 7:38) and descending doves (Matthew 3:16) as metaphors for this universal and grounding experience of spiritual encounter. Sometimes it is an uprush and sometimes it is a downrush, but it is always from a silence that is larger than you, surrounds you, and finally names the deeper truth of the full moment that is you. I call it contemplation, as did much of the older tradition.

It is always an act of faith to trust silence, because it is the strangest combination of you and not-you of all. It is deep, quiet conviction, which you are not able to prove to anyone else—and you have no need to prove it, because the knowing is so simple and clear. Silence is both humble in itself and humbling to the recipient. Silence is often a momentary revelation of your deepest self, your true self, and yet a self that you do not yet know. Spiritual knowing is from a God beyond you and a God that you do not yet fully know. The question is always the same: "How do you let them both operate as one—and trust them as yourself?" Such brazenness is precisely the meaning of faith, and why faith is still somewhat rare, compared to religion.

EVERY FEW YEARS I rediscover a song by R.E.M., “You are the Everything.” It juxtaposes despair over the state of things (“Sometimes I feel like I can't even sing / I'm very scared for this world”) with deceptively simple memories: A starry sky. The sensations of a random moment long ago. The feel of our own bodies. The sight of someone beloved (“I look at her and I see the beauty / of the light of music”).

This song gives me cathartic comfort when the news seems too much to bear. It doesn't erase famine, wars, rumors of wars, a friend's bad pathology report, or my concern over the body politic. But my position shifts; I anchor myself to the beauty of creation, to the miracle of being an embodied soul, to the fragile graces of human relationship, and to the One who brought it all into being. Thin guy wires of memory and spirit steady me against sweeping currents of events, so that I can focus on them, yet not drown.

Vincent G. Harding wrote the speech Martin Luther King Jr. delivered exactly one year before King was assassinated.

In 1851, Sojourner Truth asked a simple question: "Arn't I a Woman?" That question, though 150 years old, turned my world upside down.

Lt. William Calley was convicted for his role in leading the 1968 massacre of Vietnamese civilians at My Lai. His conviction was later overturned by Judge Robert Elliott.

Labor Day: Justice. Workers. Solidarity. Sweat of the brow. Sixteen tons and what do you get? Another day older and deeper in debt.

Or...Picnics. Beaches. Hot dogs. TV telethons.

This is the common dilemma of Labor Day. This day of rest, set aside to honor labor, is usually remembered more for the fun things you do on a day off than for the workers it honors. This is certainly not unique—look at Memorial Day or Christmas and how easy it is to be so busy enjoying them that we forget what they're supposed to be about.

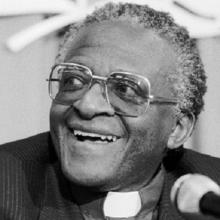

Sojourners interviewed Desmond Tutu, Nobel Peace Prize laureate and archbishop of the Anglican Church in Johannesburg, South Africa by phone on December 24, 1984.

Image: Wikimedia Commons

Sojourners' 1980 interview with the military chaplain who served the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bomb squadrons.

Watergate exposed a government whose operational principles were deceit, corruption, and manipulation.

Many Christians believe that being a Christian is likely to make one a good citizen.