When introducing people to hacking, Ali Llewellyn often brings up Apollo 13. “Remember that scene where they dump everything on the table and say, ‘We have to find a solution, with only these materials?’ And there’s, you know, duct tape? That’s all it is! Hacking is building a way to go from here to there.”

She should know. After studying church planting and social mobilization, Llewellyn went on to spearhead community engagement for NASA’s Open Innovation Program and is now a Senior Program Manager for SecondMuse, equipping hackers and non-hackers alike for the upcoming National Day of Civic Hacking.

Llewellyn’s dappled journey — from biblical scholarship to tech-minded collaboration — reveals a potent lens that Christians across denominations are using to repurpose, mobilize, and reform the church. In hacking, they see a model for the future of Christianity.

The term “hacking” has undergone a recent transformation in the popular lexicon, back to its amorally general origins as a method of discovery and recombination. For every Heartbleed-like scare today, there are innumerable cheery Buzzfeed tips to hack your life; and while the digital bandits of Anonymous capture our imagination, “hackathons” — community-oriented workshops to solve urban challenges — have popped up in many major cities.

With this broadened interpretation, Christian interest in hacking finds context. Just as faith systems give parameters to our spiritual imagination, so technology directs our inquiry into the universe and, increasingly, our connectedness to each other. Early Christianity spearheaded technological innovations with global ramifications, most notably in the invention of the codex. Today’s faithful hackers, armed with code, workshops, and participatory-minded theology, hope to do the same.

Hacking the Church

Attendance is often the first datapoint in measuring church health. But while pews cool and church doors shutter, some congregations have found willing renters with a surprising value-add: hackers focused on growing and strengthening their community. At Church of the Messiah in Detroit and St. Stephen and the Incarnation Church in Washington, D.C., a viable repurposing of church space is at work.

Mt. Elliott Makerspace is housed in the Church of the Messiah. Also called hackerspaces, makerspaces are community workshops for members to share knowledge and build things. At Mt. Elliott, screen-printing, robotics, musical instruments, and a bike shop are all available for community use and repair. Though Mt. Elliott is secular in mission, Messiah’s Reverend Barry Randolph is one of its biggest fans.

“What are ways the church is tangible in the community? [The Makerspace] is its biggest selling point. This is not just God and a bowl of soup,” Randolph said.

The teaching goes both ways. Jeff Sturges, founder of Mt. Elliott, said he was originally wary of meeting in a church. But he soon recognized that teachings like the miracle of loaves and fishes were “directly applicable to the economic challenges” he hoped to tackle in Detroit.

“At Mt. Elliott, we don’t just help out — we multiply the benefits,” Sturges said.

HacDC , the second-oldest hackerspace in the country, took up shop in St. Stephen’s in 2008. While there is not much member overlap, the relationship has developed practical value.

“One great thing about HacDC is how helpful they’ve been to us for our infrastructure and IT needs. They’ve provided equipment, a sound system, and security cameras,” said Parish Administrator Brian Best — which, for a church that has suffered many break-ins, is a relief.

For both churches, a growing awareness of and respect for alternative modes for community engagement has lead to another value payoff — relinquishing the idea of the church as the primary authority on community.

“What I’ve seen of the HacDC members … I’m guessing they’re way smarter than I am. They do calculations for fun. For this tremendous wealth of knowledge, we’re happy to share our space in exchange,” Best said.

Hacking the Community

Code for the Kingdom, a weekend hackathon run by the Leadership Network, is championing hacking as a tool to introduce the cultural market to a relevant, compelling church.

Chris Armas, a main organizer for Code for the Kingdom, believes the exploratory model and solutions-minded focus of hackathons are an access point for Christians into the exploding social tech scene. He points to the Bible App — the only Christian app to land in “top downloaded” lists — as an example of missed potential.

“The church does not have an effective model to engage for the Kingdom,” Armas said. “What if millions of people creating these new technologies had Kingdom purpose?”

Code, launched in 2013, has hosted hackathons in Seattle, Austin, and San Francisco with Valley-based coders and developers, venture capitalists, nonprofits, donors, and churches. Organized as a friendly yet intentional competition between teams, the goal is to create viable and transformative apps for social justice- and spirituality-minded users. (Past winners include UResQ, an app to report human trafficking; Deedvine, a platform to grow causes into movements; and Scriptive, a mood-mapper for tailored Scripture readings.)

Armas also sees the opportunity for physical collaboration and respectful diversity of thought and belief as vital to building bridges between tech and faith communities.

“What is necessary for people to activate? A supportive ecosystem,” Armas said.

At SecondMuse, Llewellyn believes hackathons have much to teach the church about collaboration, at the local and global scale.

Worldwide hackathons — what she calls “mass collaborations” — happen simultaneously and often interactively. For example, participants in Jakarta and Philadelphia may both identify similar public transit concerns, and share questions, solutions, and mistakes with each other in real time.

“This has profound religious implications,” Llewellyn says. “In an incredibly diverse faith world, we can collaborate with what we produce to bridge historic barriers around these stories of faith we share.”

Her dream is to replicate a participatory model she and her colleagues have built with the National Day of Civic Hacking.

“I want participatory church,” she said. “An open source theology.”

Hacking Theology

Rev. Jeremy Smith, programmer and author of popular niche blog Hacking Christianity is applying hacking principles directly to systems of belief.

“[As Christians,] We’re too often working from a place of ‘Jesus is the answer … what’s the question?’” Smith said.

“Questions are as valuable as answers. … I want to explore theology, and break it open.”

Smith hopes to use the tenets of hacking to “debug contemporary expressions of Christianity so that the faith operates more smoothly, holistically, and justly today.”

In programming terms, he calls this “constantly removing reductionist code.”

How does this analogy play out in real life? Today, Smith compares the ongoing struggle over LGBT inclusion within the United Methodist Church to running different versions of iPhone software.

“We are in the midst two different operating systems within the same church hardware,” Smith wrote in January. “ …The future [of United Methodism] is not in schism but in integration and consolidation … In the meantime, 1.0 and 2.0 can continue to worship, serve, learn, and preach Christ resurrected side-by-side.”

“Breaking theology” is a serious invitation. It begs the question: How do we break well?

Smith cautions against individualism, instead stressing communal exploration.

“The sin of hacking is hubris,” Smith said. “If you think you are much smarter than the councils, the bishops … that may or may not be true. This is less about going your own way, and all about accountability.”

To Llewellyn, cooperation is both imperative and freeing. “Mass collaboration holds the insistence that diversity of perspective makes us all stronger,” she said.

Bottom-Up Participation

Participatory church, at the scale that Armas, Llewellyn, and Smith envision, is far off yet. Of the individuals with whom Sojourners spoke, none was aware of the others’ work. The movement, if there is to be one, has yet to find many of its own members.

And one barrier to a coherent ethic of faithful hacking is a narrative history that is dominated by economically privileged white men.

“The concept of putting a makerspace somewhere other than where you can find young white men who are technically skilled is really, really new,” said Sturges, of Mt Elliot.

Llewellyn knows this personally. She trained for ministry at an “extremely evangelical Anglican seminary,” where “a lot of professors didn’t think women could be ordained.”

Now, in the hacking world, “I am frequently the only woman,” said Llewellyn.

Even so, her delight in both communities in palpable.

“If we can create a culture where we don’t walk away from people — that’s really vital to the communities we try to create. We have to know how to play together.”

And indeed, far from calling for a split from their current institutions, these church-minded hackers are advocating for internal reform — making existing faith frameworks better, not necessarily making them anew.

For a religion consistently depicted as dying, this engaged mindset is distinctly optimistic.

Earlier in 2014, 25 ministers from Detroit gathered at Messiah and ended up meeting in the Makerspace.

“It was hard to conduct the meeting because everyone had so many questions about the space. ‘How did you do this?’ ‘How did you get it started?’” Rev. Randolph says.

He sees the ministers’ interest in the secular, community-minded makerspace as a sign of the future of the church.

“This is what the role of church as rebuilders of community looks like. This is a community without walls — Christian and non-Christian, black and white. That’s how you build a kingdom,” he said.

Catherine Woodiwiss is Associate Web Editor for Sojourners. Follow her on Twitter @chwoodiwiss.

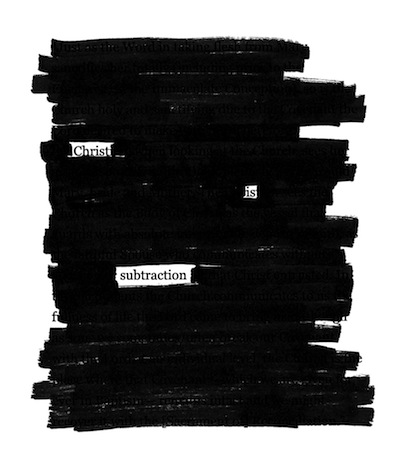

Image: Excerpt from Pope Francis' (then-Cardinal Bergoglio) 2008 Catechesis at the Eucharistic Congress in Quebec.

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!