Share As A Gift

Share a paywall-free link to this article.

This feature is only available for subscribers.

Start your subscription for as low as $4.95. Already a subscriber?

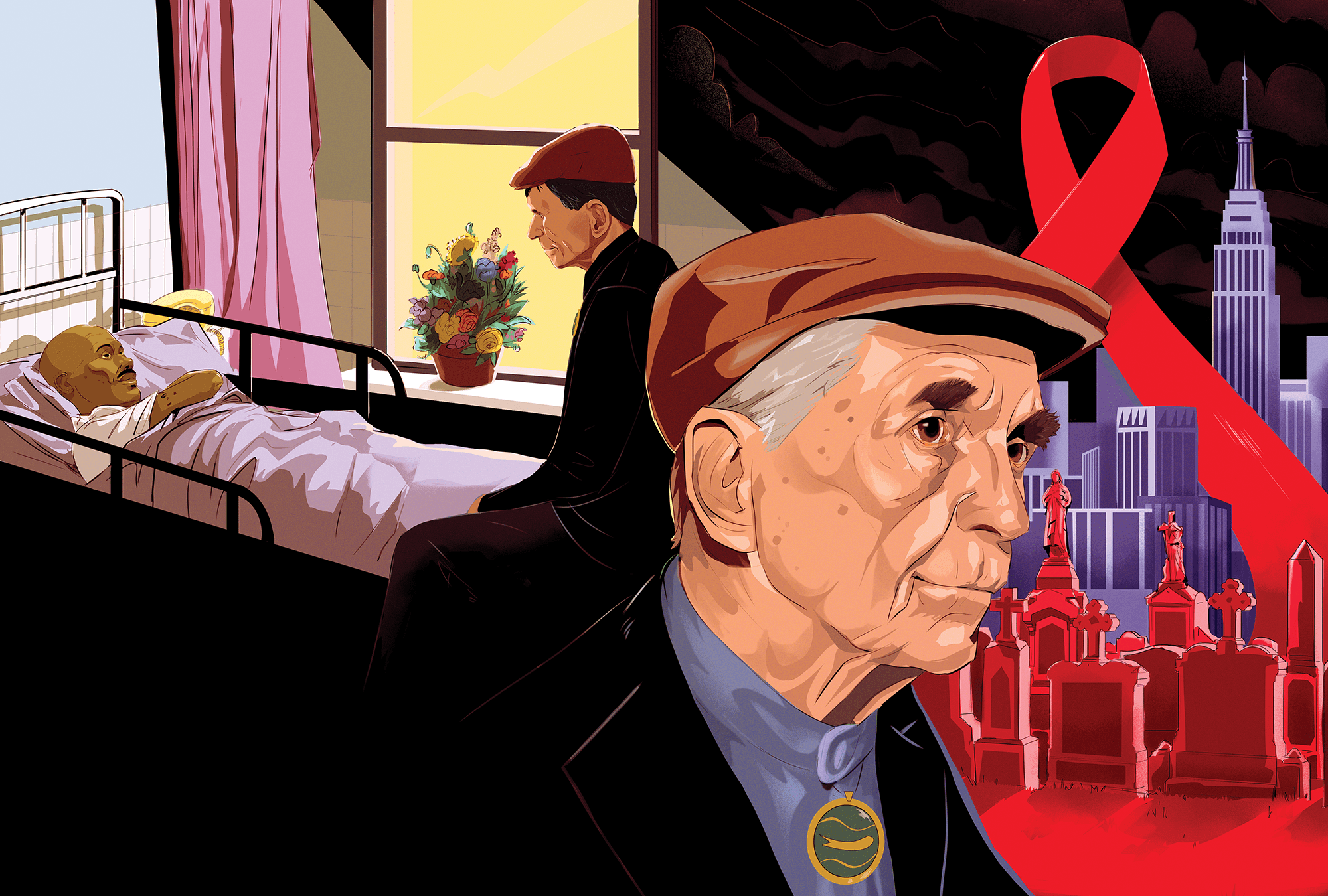

Illustrations by Ryan Inzana

DANIEL BERRIGAN WAS one of the best-known American peace activists of the 20th century. But there’s a lesser-known aspect of his Christian commitment worth noting as we celebrate the centennial of Berrigan’s birth on May 9: his work on behalf of the material and spiritual needs of New York City’s “discarded souls,” in particular those suffering the ravages of cancer and HIV/AIDS.

Berrigan’s peace activism had deep roots. In 1964, he co-founded the Catholic Peace Fellowship. In 1967, he and his brother, Phil, became the first Catholic priests to be arrested for opposing the war in Vietnam. In May 1968, Berrigan and eight others, including Phil—in an act that would change the nature of Christian nonviolent resistance—entered Local Draft Board No. 33 in Catonsville, Md. The nine seized Selective Service records and burned them outside the building with homemade napalm. For these actions, recounted in Berrigan’s play (and later movie) The Trial of the Catonsville Nine, he served 18 months of a three-year sentence in Danbury Federal Prison.

In 1980, Berrigan took part in the first Plowshares action at the General Electric nuclear missile facility in King of Prussia, Pa., where, in a symbolic disarmament, participants damaged two nose cones of Mark 12A missiles and poured their blood on secret blueprints. Berrigan continued to protest the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan and the continued construction of nuclear weapons until his death in 2016.

Daniel Berrigan became a cultural icon, appearing with his brother on the Jan. 25, 1971, cover of Time magazine (“Rebel Priests: The Curious Case of the Berrigans”). Over the years, Berrigan, an award-winning poet, published more than 50 books of poetry, plays, social criticism, and, above all, biblical and religious commentary. He taught at Fordham, Yale, Columbia, and Loyola University New Orleans, reaching thousands of students with his message of nonviolence. Actor Martin Sheen, who was arrested dozens of times with Berrigan, claimed that Dorothy Day got him back to the church and Berrigan kept him there. In 1986, Berrigan appeared in Roland Joffé’s film The Mission and began a close friendship with the film’s star, Jeremy Irons, whose son he would baptize. Berrigan’s May 6, 2016, funeral at St. Francis Xavier Church in Manhattan was attended by hundreds of people, including Dar Williams who sang “I Had No Right,” the song she had composed for Berrigan years before.

Berrigan’s work with people at the end of their lives is a less celebrated, but no less important, part of his story.

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!