When Stacey Merkt sent her contribution to this issue, she was in the middle of a complex legal situation, the outcome of which was uncertain. The details and history of her sentencing are included in her article.

After her reflections arrived, Stacey was ordered to report to the Fort Worth, Texas, Federal Correctional Institution. On Jan. 29, 1987, she began serving a 179-day sentence for conspiracy to transport refugees from El Salvador. U.S. District Court Judge Filemon Vela intentionally gave her a sentence one day short of six months so that she is ineligible for parole. She was due to deliver her first child within a week after being released from jail.

- The Editors

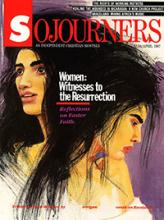

Being a woman, I think it's wonderful that it was other women who discovered the empty tomb, the resurrected Christ. I am not surprised at their perseverance, their daring, their commitment made evident by their presence at the tomb and its sadness.

Does such perseverance, daring, and commitment exist today? I say yes. I have seen it - in people from El Salvador and in people in the United States.

And are we present today not only at the sunrise service of resurrection but also at the journey, the crucifixion, and the empty tomb?

I cannot begin to think about the resurrection without first talking about the passion and crucifixion, without which there is no resurrection. When I think of Christ's journey, which included so much sacrifice and suffering, I cannot help thinking of the Salvadoran people. El Salvador - a country where war's violence raged from 1979 to 1992, causing approximately 75,000 deaths and more than 500,000 of its people to flee.

Read the Full Article