Share As A Gift

Share a paywall-free link to this article.

This feature is only available for subscribers.

Start your subscription for as low as $4.95. Already a subscriber?

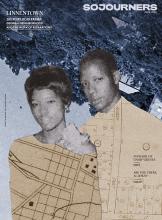

Illustrations by Trevor Davis

WEEDS GROW THROUGH a rusted wash pail in a thicket beside the University of Georgia’s West Parking Deck in Athens, Ga. Littered with the detritus of college life — beer cans, a condom wrapper, Styrofoam containers — this area, unlike the otherwise pristine campus, is neglected and uninviting. Walk in anyway. Look under brambles to find a bent scrap of aluminum roofing, a green Coca-Cola bottle, a cooking pot, and a plastic toy rifle. These objects, buried under vines and rotting logs, form the understory of what used to be a working-class African American neighborhood called Linnentown. Children would swing from grapevines to get across the creek. Now college students, high-rise dorms, and cars swirl above the 22 acres of the erased community. This patch of land, mostly buried under concrete and steel, was stolen from the Cherokee and Creek people first, but the people who remember the second forced removal are still alive. They can’t get their land back, but there is a growing movement for redress for communities like Linnentown.

From 1962 to 1966, the city of Athens used eminent domain under the Urban Renewal Act to force Linnentown residents out of their homes so that the University of Georgia could build three dormitories and a parking lot for their growing, mostly white, student body.

The children of Linnentown are in their 70s and 80s now. As a child, Hattie Thomas Whitehead ran from yard to yard with her playmates and sometimes snatched pears from Ms. Susie Ray’s tree. Christine Davis Johnson enjoyed pears, apples, and pomegranates from the trees in her own yard. They both remember the bulldozers running in the middle of the night, the intentional fires, and the sense of outrage when their parents and neighbors were forced to accept a pittance for their homes and land.

“It was a warm place to live,” remembered Johnson, who was 20 in 1963 when she and her newly widowed mother had to move. Johnson bore double grief that year from her father’s death and the loss of her childhood home. “No hate. My mother didn’t teach me hate,” Johnson said, as she thought about how her tight-knit community was torn asunder. “It’s gone, it’s over, don’t go back,” her mother would say to her. Against her mother’s advice, Johnson would sometimes drive through what used to be her neighborhood, just to remember.

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!