“WE ABUSE LAND because we regard it as a commodity belonging to us. When we see land as a community to which we belong, we may begin to use it with love and respect.” So wrote Aldo Leopold in his ecological classic A Sand County Almanac, published in 1949. That same year, Erle Halliburton experimented with pumping a slurry of oil and sand into a wellhole in Oklahoma, patenting a new process he dubbed “Hydrafrac.” Within the next five years, Halliburton was treating more than 3,000 wells a month that way.

Short for “hydraulic fracturing,” fracking—a word now included in Merriam-Webster—is the process of drilling and injecting fluid into the ground at high pressure in order to release oil or natural gas inside. Today, thanks to recent technological developments, more than a million fracking sites dot the U.S. landscape.

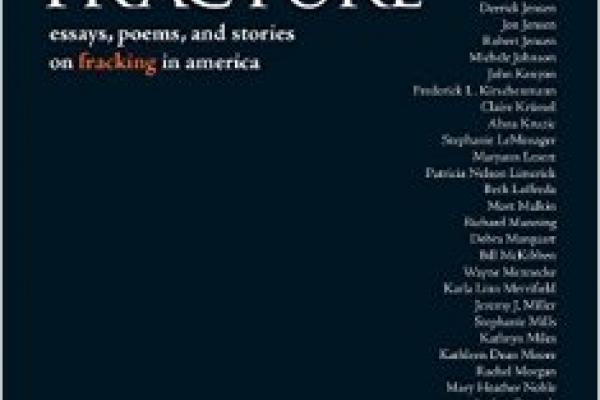

The environmental vision of Leopold and the actions of Halliburton that fateful March both haunt the recent literary collection Fracture: Essays, Poems, and Stories on Fracking in America. With literary genres that range from verse to essay and fable to investigative journalism, Fracture chronicles the ecological and cultural ruptures resulting from this highly controversial phenomenon. Co-editors Taylor Brorby and Stefanie Brook Trout have put together a devastating, disturbing collection that should be read in small bits, lest you be overwhelmed.

Read the Full Article