IT BEGINS WITH SPEED, the red flash of taillights in the night, the illuminated city bright against the dark. Over the images we hear a voice, resonant in its drawl as the images move to decimated mountains, poisoned streams, and rushing city crowds. The landscapes are swallowed by machines, the people lost to their digital devices as the voice offers a poem about a nightmare where all is sacrificed for an abstract “Objective.” On-screen we are seeing that nightmare, and it looks very much like our daily lives.

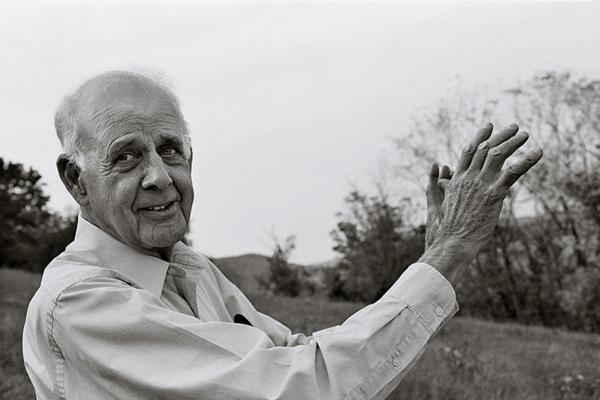

The speaker is Wendell Berry, the poet, farmer, and prophet who has been among America’s most sustained voices for the created world and the people and places that are among its members. Many of those who have read Berry say he changed their lives, but even though he has published more than 50 books and won literary accolades, including a National Humanities Medal given to him by President Obama, Berry is not particularly well known in many circles. It was that widespread lack of familiarity with Berry and the urgent goodness of his vision that prompted filmmaker Laura Dunn to create her latest film, Look and See.

Read the Full Article