RECOUNTING THE STORIES that shape our religious longings happens in the shade of uncertainty and fear. We remain in “Ordinary Time” but are besieged by a global pandemic with fallout the likes of which we cannot yet know. It would be easy to scapegoat people or to descend into fear. But we are called to live out our faith, even in difficult times—or maybe especially in difficult times.

We know we are constantly being shaped by our histories, in every way. Telling the stories of how we’ve come through in the past and grounding ourselves again in the firm foundation of our faith will, over time, reveal to us how that foundation shaped our lives in this season. It may embolden us to join God’s project of salvation, deliverance, and freedom for all creation. With Christ at the center of our lives, we have a constant invitation to return to the source and to center our lives in God in such a way that we see our responsibility to live, on behalf of this world, in the name of Christ. It pushes us beyond our circles of family and friends and helps us to see a larger connection, deeper relationships. Perhaps if we can get there, we will be able to see our need to repent from our self-absorption. We might be able to see that we are a web of relationships and—just as Moses needed the help of at least five women—that we need one another to survive.

August 2

Wrestling a Blessing

Genesis 32:22-31; Psalm 17:1-7, 15; Romans 9:1-5; Matthew 14:13-21

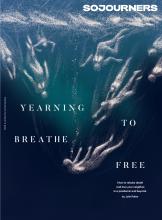

IN GENESIS 32, Jacob wrestles a blessing from the man at the river Jabbok, but not without cost. Jacob says he’s seen God face to face (32:30), something Moses would later be told is impossible. There has been much scholarship on whether the man with whom Jacob wrestles is God or an angel. The text is fully ambiguous. But it seems clear that Jacob wrestled in the night because he was afraid to face his past. He feared the coming confrontation with Esau.

I have had internal wrestling matches that have felt like I was in hand-to-hand combat with myself. Lately, I’ve been wondering whether our nation can wrestle with its internal beginnings, with its demons and angels—with its past. Recent events where Black people have died either in vigilante killings, such as Ahmaud Arbery in Georgia, or state-sanctioned police killings, such as the murders of Breonna Taylor and George Floyd, tell me we still have some communal wrestling to do, in hopes of finding a new name that includes “justice.” Jacob needed to win because from his lineage would come the patriarch from whom came the messiah who “God blessed forever” (Romans 9:5). If people will know God’s blessings, they must find a way to live into what is right for the sake of us all.

Read the Full Article