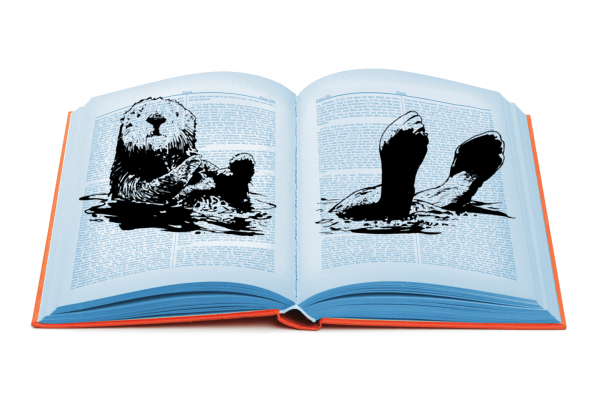

TOURISTS SPOTTED OTTERS in the Potomac River this spring. Not unheard of, but rare.

North American river otters are the only otter species in the Chesapeake Bay watershed. For millennia they were an apex species that served as “doctors” for healthy ecosystems by maintaining population levels of fish, frogs, and insects. The Colonial-era transnational fur trade, and its modern-era descendants of land destruction and water pollution, brought otters to the brink of decimation.

Now the otters are returning, a signal that decades of reparatory work to protect the Chesapeake watershed is having modest success.

The word most associated with these agile water weasels is “play.” Play is a fundamental way of interacting in the world; it’s how creatures “practice into being” what we can only imagine at first. Play develops communal trust, agility, resilience, strength, and strategy—and situates the soul firmly in the individual and social body.

Read the Full Article