WE HAVE BUILT an entire political economy that relies on racism. We can no more give up the racism than we can give up the political economy that funds our lives. Racism persists because racism works. It does not, of course, work for all of us — but that is somewhat the point.

Racism naturalizes what are obviously unnatural relationships forced between value and labor and land and bodies. As the ultimate gaslighting move, racism blames the oppressed for their oppressions, claiming it is something “natural” about them, something about their “race.” This naturalization attempts to justify the morally unjustifiable and makes what is obviously evil, idolatrous, and abhorrent look good, true, and beautiful. Following the Black radical tradition, we can call this gaslit normalization of domination and exploitation “racial capitalism.”

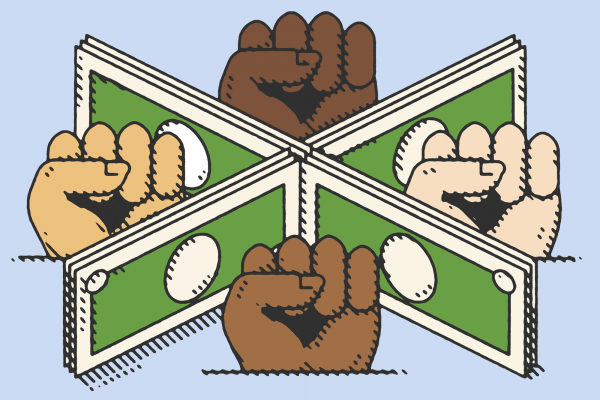

Racial capitalism has built into its politics a divide-and-conquer strategy. The Black Marxist Oliver Cromwell Cox laid this out in 1948 when he observed that poor whites, migrant Chinese, and Jim Crow-era African Americans suffered similar, if also unique, oppressions at the hands of politicians, factory owners, planters, labor agents, managerial elites, and so on, but it was the fate of those crushed by racial capitalism to blame one another while giving a free pass to those most responsible for their sorry lot. Rather than finding ways to build coalitional solidarity against oppressors, they became divided by race. In this scenario, oppressed whites sided with their white oppressors in exchange for what W.E.B. Du Bois called the “public and psychological wage” of white racial identity — and many participated in all manner of white supremacist violence to seal the deal. All the while, African Americans and Chinese were made out to be enemies of the nation and of one another.

In explaining the mindset normalizing chattel slavery in colonial America, social anthropologist Audrey Smedley pointed to the role of conventions. “Conscientiously moral human beings do not conventionalize such habits of thought and behavior without formulating a rationalizing ideology,” she wrote. Such conventionalization amounts to a culture of domination. If you want to challenge that culture, you need to dismantle enough of it to destabilize the conventions, and to destabilize the conventions, you’re going to need to dismantle the world comprised of those conventions.

In the 1980s, we saw the emergence of a global neoliberal capitalism that was similarly racialized and intended to divide and conquer. Among other things, neoliberalism splintered the political Left. Some remained committed to questions of class, gender, and respective identities as part of a liberative project. Others adopted the shift from democratic citizen to consumer in transnational capitalism. There emerged a perspective that essentialized the identities themselves — as if one’s identity became a self-interpreting, self-realizing project. This latter reality, grafted on to the ascent of a therapeutic culture, centered around the moral ideal of personal authenticity. We saw the rise of “identity politics,” with no clear connection to the liberative realities out of which those identities, such as Asian American, first emerged.

This is largely where we are now: each one individually burdened with a project of asserting, securing, and protecting their own identities. We even introduce ourselves and our identities in competition with other identities. What you’ll notice about this history is that it’s remarkably similar to the creation of “race” at the beginning of the United States, when constituent racial identities were created as a divide-and-conquer strategy. Identity politics allows racial capitalism to be normalized so it can continue to dominate and work for economic elites.

I believe we are at an inflection point. We are weaving our identities back into the history of our communities and their larger socio-political realities. We have an opportunity to move from a deeply individual identity project to a more public political one driven to collective liberation, where lived experience becomes the substance of identity and liberation becomes its vocation and direction.

Much of my analysis follows a Marxist critique of the ideology of race. But there is one place I understand Christianity as departing significantly from Marxism. Marxists are waiting for a revolution to start. Christians are living into a revolution that is 2,000 years old.

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!