ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE IS all the buzz as I write this. It’s been impossible to ignore the omnipresent chatter about AI, from the deluge of online commentary to congressional hearings. As I thought about adding to the chatter — er, providing some insightful perspective from a progressive theological point of view — I wondered what more could be said. So, I decided to ask AI. I prompted Microsoft’s Bing AI chatbot to draft an essay, “from a progressive Christian perspective,” on the dangers of AI. The first line of the response: “As an AI language model, I am not capable of having a religious belief or point of view.”

Well, that’s reassuring.

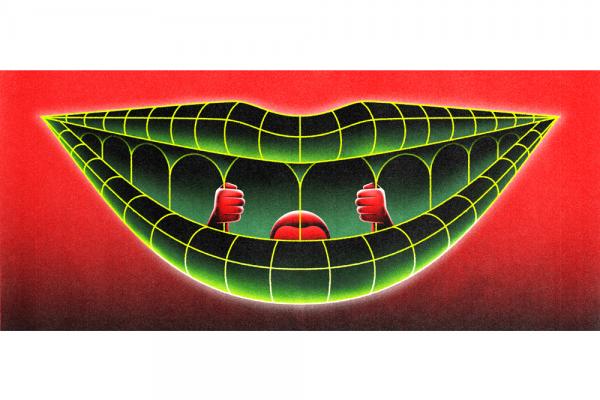

Concerns about AI aren’t new — science fiction writers have painted grim pictures of machine consciousness at least since Samuel Butler’s 1872 novel Erewhon (wherein Butler wrote in his three-chapter “The Book of the Machines” that “there is reason to hope that the machines will use us kindly, for their existence will be in a great measure dependent upon ours; they will rule us with a rod of iron, but they will not eat us.” One hopes that we’ll find better reasons to hope.). Warnings of apocalyptic totalism abound: In May, Matthew Hutson wrote in The New Yorker, “In the worst-case scenario envisioned by [artificial-intelligence doomers], uncontrollable AIs could infiltrate every aspect of our technological lives, disrupting or redirecting our infrastructure, financial systems, communications, and more.”

Since the Bing chatbot is incapable of offering a theological perspective, I asked scholar Walter Brueggemann for his thoughts.

Read the Full Article