Share As A Gift

Share a paywall-free link to this article.

This feature is only available for subscribers.

Start your subscription for as low as $4.95. Already a subscriber?

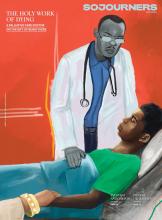

Illustrations by Kalima Alain

I LIVE IN Rwanda, a beautiful East African country also called the Land of a Thousand Hills. We have a saying here: “When you are well, you belong to yourself, but when you are sick, you belong to your family.” But my first trip to the United States taught me that culture matters, particularly in the context of end-of-life care.

In a palliative care education and practice course at Harvard Medical School, I learned the principle of patient autonomy — that individuals have the ultimate authority to make decisions about their own health care. Patients are “in control.” But while shadowing my mentor at Massachusetts General Hospital, I noticed photos of family members in patients’ rooms. I remember asking, “Where are the people who are shown in the photographs?” I now know that this may be an attempt to recreate a family or to provide a last chance to reconnect with life, but all the people I saw in the pictures were alive — why were people trying to create an illusion of family when the family exists?

I asked my mentor, “How can we bring back those people from the photos to the room?”

Of course, I came with my bias and an African perspective on end-of-life care. Here, decision-making is based on patient autonomy and community responsibility, because one aspect does not exclude the other. There is synergy between them.

In Rwanda, there are no photos in the patient’s room. Instead, there are people.

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!