“WE ARE IN the midst of an overdose crisis,” said Hill Brown, southern director of Faith in Harm Reduction. “We say overdose crisis and not opioid crisis because right now overdose is the crisis. We’ve had opioids forever.”

In 2020 and 2021, during the height of deaths and extreme social isolation from COVID-19, deaths from overdoses surged in the United States before reaching a new baseline. The CDC estimates nearly 110,000 overdose deaths in the 12 months ending November 2023. That’s up from 71,350 deaths in the 12 months ending November 2019. Nearly 70 percent of these deaths were related to fentanyl and other synthetic opioids. For people 35 to 64 years old, the overdose death rate was highest among Black men and American Indian/Native Alaskan men at around 60 per 100,000 persons. Overdoses have become the third largest cause of death among teens 14 to 18 years of age, behind firearm deaths and vehicle collisions, rising to an average of 22 per week in 2022, largely driven by fentanyl in counterfeit prescription pills.

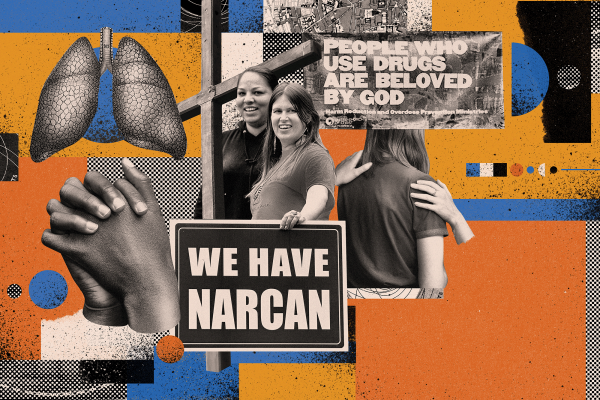

While churches have long hosted recovery groups focused on abstinence from drugs, some faith leaders are exploring how churches and other religious institutions can serve people who use drugs (PWUDs). By offering safer drug use resources such as sterile syringes and smoking supplies, fentanyl test strips, safe consumption sites, naloxone (an overdose reversal drug) training, and counseling, they are also working to extend this welcome and compassion without moralizing about drug use or judging PWUDs.

Collectively known as harm reduction, these practices were originally envisioned as strategies to curtail the spread of HIV. In this context, harm reduction aims to reduce the negative consequences associated with drug use. Its values include viewing PWUDs as sacred and beloved, believing love is greater than the law, allowing PWUDs to exercise choice, and centering a person-first approach that embodies compassion, dignity, and justice.

Read the Full Article