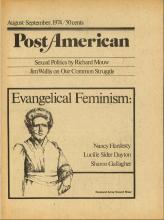

In fact, if one focuses on the more activistic sons and daughters of the 13th-century “Evangelical Awakenings” (rather than on the more doctrinally-oriented forerunners of American fundamentalism), one can make a case that these persons were often the social radicals of earlier generations. In the first essay in this series, we tried to show that this was true for the heart of American “establishment evangelicalism”--Wheaton College and its founder Jonathan Blanchard. In this essay we would like to unfold something of the history of “evangelical feminism.”

The Wesleyan revival occurred at a crucial time in England’s history and was a part of (perhaps to some extent the cause of) a certain breaking down of older aristocratic and hierarchical patterns of society. A case can be made, in fact, that Methodism helped mediate in a peaceful way some of the radical social ideas of the more violent French Revolution (cf. Bernard Semmel’s recent book The Methodist Revolution). Such currents helped pave the way for new roles for women. As a “religion of the heart” rather than tradition or training, Methodism was a natural “leveler” more open to involvement of lower classes, laymen, women, and others held in check by more “established” and “hierarchical” forms of religion.

Read the Full Article