It was not the kind of heralded Washington arrival (usually reserved for queens, popes, Soviet premiers, and Patriot missiles) that gets written up in the Style section of The Washington Post. Barb and Jim Tamialis, with 1-year-old Michael, 2-month-old Nathan, and a puppy, inconspicuously crossed the threshold into their new home on 17th Street -- to discover layers of dirt, discarded furniture, peeling paint in a shade dubbed "swimming pool green"and a man on the first floor. Everything but the kitchen sink -- literally. And no oven.

For two-and-a-half weeks they cleaned, throwing old mattresses out the window into the backyard, sterilizing baby bottles in an electric coffee pot, cooking on a hotplate, and praying for the plumber to arrive. On Labor Day weekend, two cars and a moving van from Chicago pulled up next door.

A troop of children from the neighborhood witnessed the arrival of this unusual, long-haired group. The 11 sisters and brothers of the Williams family helped carry in their belongings and then laid claim to the discarded mattresses for tumbling in the alley.

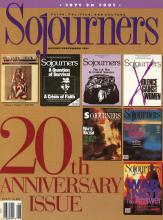

Altogether 20 people had made the move to Washington, DC in the summer of 1975 to make a new life in the two houses on 17th Street. For some, their first experience of intentional community -- though they wouldn't have called it that then -- had been in the home of the Jolly Green Giant in a suburb of Chicago in 1971. Seven students from Trinity Evangelical Divinity School had responded to an announcement on a seminary bulletin board requesting students to paint and house-sit that summer. The house, it turned out, belonged to the radio personality behind the famous "Ho, ho, ho." There the first issue of The Post-American, forerunner to Sojourners, was created.

Read the Full Article