There was a time in the early history of the church when prophets were held in unique honor: Their spiritual gifts ranked with those of the Apostles themselves. One second-century document on church order states that if a prophet is present at the Lord's Supper, he or she is the one to preside, as having the most conspicuous endowment of the Holy Spirit.

Today prophets are likely to lead more marginated lives—nervously acknowledged as having something significant to say, but not in a position of power from which to say it. So firm is the church's foundation that it does not budge easily; prophets are not inclined to respect so specific a gravity. For their own part, the guardians of organized religion recognize that there is a prestige factor in having a prophet, but it is more tranquil to have her or him at a little distance.

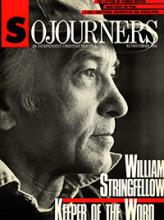

When William Stringfellow, one of the most authentic prophets of our place and time, died, the writer of his obituary in The New York Times referred to him as "an activist of the '60s." The wording is a sort of distancing in itself: It puts the man Stringfellow into a sort of journalistic protective custody as someone who had a sort of significance back in those wild days.

But for those who recognized him as a prophet, William Stringfellow was a contemporary person in our midst. He was most acutely heard by people who are themselves somewhat marginated: social critics, questioners of authority, anyone sensitized to the abuse of power, anyone who recognizes the idolatry in social standards and political ambition, who cries out against the creeping decay that eats away at institutions.

Read the Full Article