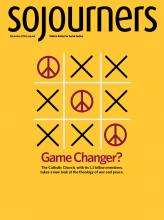

AFTER 52 YEARS of war and four years of negotiations, a peace accord was signed in late September between the Colombian government and FARC rebels. Six days later, a national referendum failed to bring the accord into force.

Within a few days of the referendum, a massive popular movement took to the streets of Colombia’s major cities to ensure that negotiations continued. Then, Colombian president Juan Manuel Santos, but not his FARC counterpart, was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize.

These events have been a roller-coaster ride for Colombian churches, which have been working toward this accord for decades. Colombian Christians have played an important, if often behind-the-scenes, role in advancing peace in this country.

The Catholic Church helped facilitate the highly secret early dialogue between government and rebel leaders, paving the way for the current peace process. Mennonites have worked for more than 25 years for the right to conscientious objection in a country with mandatory military service for all males. In a landmark decision, this year the Colombian military officially granted conscientious objector status to a potential recruit, Juan José Marín Gómez.

In 2015, FARC guerrillas called on “civil society and churches” to monitor their unilateral ceasefire. The Interchurch Dialogue for Peace in Colombia (DiPaz), which includes Protestants, Anabaptists, and Catholics, jumped at the opportunity. “We worked with other civil society organizations and contacted networks of churches all over Colombia, seeking information any time there were reports of a possible ceasefire violation,” said Angélica Rincón, who coordinated the monitoring for DiPaz. “In one of our first surveys, we heard back from numerous pastors in conflict areas saying that this was the most peace they had ever experienced.” The ceasefire held, and conflict-related violence dropped to the lowest levels in more than 50 years.

Read the Full Article