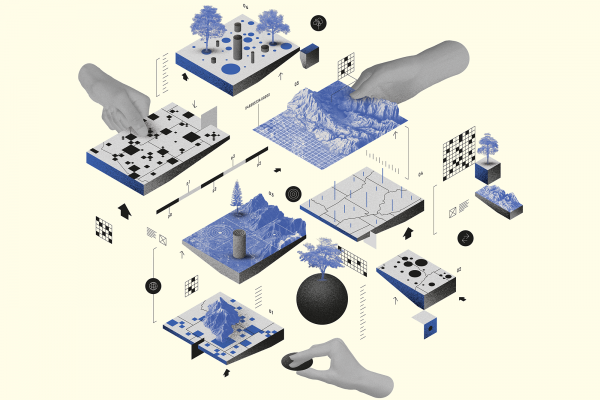

MAPS ARE NOT just drawings of a place; they are also windows into a perspective. In the era of European colonial expansion, maps were essential tools.

The 15th century imperial edicts known collectively as the Doctrine of Discovery theologically and politically justified the brutal seizure of land not inhabited by European Christians. This set into motion a new worldview that is the basis for all modern property ownership and established a relationship to the land based on colonization rather than habitation. As a result of this and other political arrangements, the Roman Catholic Church controls about 177 million acres of land around the world.

Molly Burhans is a Catholic, an activist, and an entrepreneur. She is also a cartographer and geographic information system (GIS) analyst who sees the church’s landholdings as an opportunity for a global spiritual and ecological transformation. If church maps in the past too often represented cultural oppression and land domination, the maps Burhans creates are powerful tools for ecological regeneration and social repair.

Read the Full Article