Share As A Gift

Share a paywall-free link to this article.

This feature is only available for subscribers.

Start your subscription for as low as $4.95. Already a subscriber?

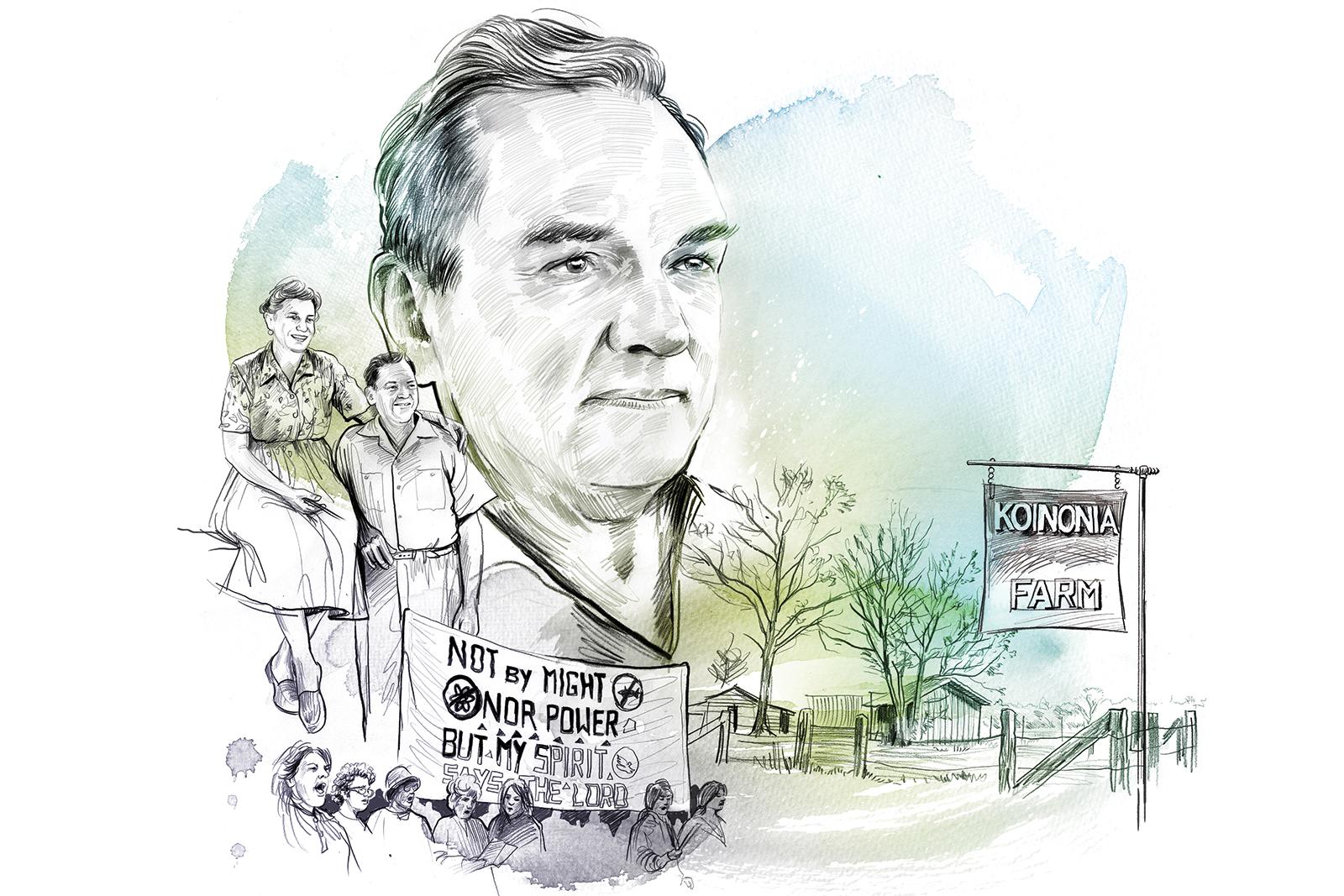

Illustration by Julian Rentzsch

CLARENCE L. JORDAN died on Oct. 29, 1969, at 57 years old.

The radical Southerner who dedicated his life to farming, sharing the gospel, and imploring his neighbors to actually follow Jesus is not widely remembered. Jordan died as simply as he lived — buried in a wooden box used to ship coffins, in an unmarked grave, and wearing his overalls.

In early 2020, a little more than 50 years after Jordan (pronounced “Jurden”) died, I came across his work and was enamored. I began reading anything from or about him I could find. Jordan’s Georgia roots and love for the South mirrored my own. His charm and cutting humor were irresistible. Most appealing was Jordan’s stubborn commitment to radically following Christ, which led him to reject and rebuke the practices of racism, capitalism, and militarism in the U.S.

On the podcast Pass the Mic, writer Danté Stewart put a name to what I found in Jordan. “The reason why white [siblings] are struggling in this moment is because most of their models have been violent white supremacists,” Stewart said. “White [siblings], they don’t have models of liberation and love, so therefore they’re struggling in this moment.”

Clarence Jordan was a “model of love and liberation” that we can learn from now. The dehumanizing forces of racial capitalism and militarism are no weaker in the U.S. today than in his lifetime, and many white Christians are avid proponents of both. Jordan’s resistance and radical theology did not die with him; instead, they can evolve and grow with the times. We should engage Jordan without idolizing him and advance his core commitments with a critical eye, honestly appropriating them for our modern struggles.

IN 1942, CLARENCE and his wife, Florence Jordan — with Martin and Mabel England — co-founded Koinonia Farm. The couples set out to form an “agricultural missionary enterprise” in Americus, Ga., naming Koinonia after the Greek word for fellowship and joint participation. The farm would be “cooperative and communal ... interracial, controlled by investment of time (life), rather than capital; based on the principle of distribution according to need; [and] motivated by Christian love as the most powerful instrument known to [people] for solving [their] problems,” according to a letter sent by Clarence.

Koinonia bucked norms from the moment they established themselves on the 440-acre “demonstration plot for the kingdom.” Farm members were preaching and practicing pacifism (a year after the United States joined WWII), racial equality (in the segregated South), and joint ownership of all possessions (as the second Red Scare was ramping up). Believing that Christians had an obligation to work with and for the poor, Koinonia disregarded racist “Southern tradition” in several ways. They paid Black and white laborers equally and ate together. The farm had a “cow library,” loaning a milking cow to any of their neighbors unable to afford milk.

The people of Koinonia were practicing solidarity, not charity. The sharing of resources and knowledge was often reciprocal — neighbors would teach the intricacies of farming Georgia clay, and the Jordans would share what Clarence learned studying agriculture at the University of Georgia.

In 1956, two years after the Supreme Court ruled that segregation was unconstitutional, a quarter of the residents at Koinonia were Black. After the court’s decision, Jordan aided two Black students in their application to a segregated college in Atlanta, catching the attention of his neighbors. A White Citizens’ Council in Sumter County was started “with the express purpose of getting Koinonia out,” according to Florence. Anonymous threats, economic and political opposition, and outright violence soon came to the farm.

A 1957 article in the Watsonville Register-Pajaronian recounted the aggression Koinonia faced: Banks, gas stations, feed stores, and most businesses in Americus boycotted the farm (one feed store defied the boycott — it was dynamited shortly after); State Farm and other companies canceled all of Koinonia’s insurance policies; at night, people fired pistols and rifles at Koinonia; twice Koinonia had its roadside farm stand dynamited, and other property was destroyed. That year, a Sumter County grand jury issued a report accusing Koinonia of being a communist front and faking the violence. The Georgia Bureau of Investigation and the FBI began investigating Koinonia for their alleged communist ties. While Jordan rejected the USSR’s communism mainly for its atheistic components, he would later quip that any Christians who weren’t accused of being communist weren’t worth their salt.

Koinonia was such a thorn in Georgia’s side that William T. Bodenhamer, a state representative and Baptist minister, pledged in his 1958 gubernatorial campaign that if elected, he would close Koinonia. One afternoon, a parade of Ku Klux Klan members came to intimidate the people of Koinonia into selling the farm.

Illustration by Julian Rentzsch

Despite the stress, Koinonia stood firm. The Jordans believed they were called to continue working the land and sharing the gospel and held these as equal priorities. “All my life I have felt it important to stay close to people and the soil, so I farm with poor people,” Clarence said. “While I love books and have a passion for knowledge, I have thought the real laboratory for learning was not the classroom but in the fields, by farming, and in interaction with human need.”

When Clarence was on speaking tours, Florence was leading the farm and keeping the books. Koinonia became a house of hospitality for the wider network of justice. The farm hosted Christian leaders from Dorothy Day to Vincent Harding, as well as other visitors — about 1,000 to 1,500 each year in the ’60s, according to Lenny Jordan, the youngest of the Jordans’ four children. Florence, according to Lenny, loved “entertaining” and would always make the time and space for coffee, conversation, and companionship. Her legacy is less well recorded than Clarence’s, partially because of the patriarchy of the 20th century and partially because of Florence’s disposition, but it would be hard to overstate how crucial she was as a leader on the farm and as Clarence’s co-laborer. “My mom really was the one who supported him,” Lenny said. “She wasn’t afraid of telling him what she thought about how things should be done, and he was just as open to hearing from her and encouraging her to talk to [others.]”

EVENTUALLY, THE VIOLENCE subsided, and Clarence spent more time on his writing. Many of his speeches were transcribed and collected in books and recordings. His best-known work was Cotton Patch Gospel, which “translated” the New Testament into the 20th-century South. Cotton Patch has Paul writing to the Christians in Washington (Romans), Atlanta (Corinthians), and Selma (Thessalonians). Jesus is baptized in the Chattahoochee River.

“The poor are God’s people, because the God Movement is yours,” Jesus declares in chapter 6 of “Jesus’ Doings” (Luke). “You who are now hungering are God’s people, because you will be filled. You who are now weeping are God’s people, because you will laugh ... BUT — It will be hell for you rich people, because you’ve had your fling. It will be hell for you whose bellies are full now, because you will go hungry.” Several translation choices in Cotton Patch are rather salty. Jordan does a helluva job setting the language in the mid-20th-century South — and some of that language doesn’t bear repeating, even if accurate for the time.

Jordan wrote and published Cotton Patch in sections — starting with Paul’s letters and moving later to the gospels. Some of Jordan’s translations were errors, in my view. For instance, he translates Jewish believers, whom Paul rebukes in their exclusion of Gentile Christians, as the white folk who segregate their churches and oppress Black people. This comparison fails in the rest of the New Testament, where the Jews are oppressed people.

At other times, Cotton Patch shines for its blunt translation choices. Most notably, Christ is not crucified — he is lynched. Jordan is not the first or last to make this observation, but it’s worth quoting his explanation at length:

“We have thus emptied the term ‘crucifixion’ of its original content of terrific emotion, of violence, of indignity and stigma, of defeat,” Jordan wrote. “I have translated it as ‘lynching,’ well aware that this is not technically correct. Jesus was officially tried and legally condemned, elements generally lacking in a lynching. But having observed the operation of Southern ‘justice,’ and at times been its victim, I can testify that more people have been lynched ‘by judicial action’ than by unofficial ropes ... They crucified him in Judea and they strung him up in Georgia, with a noose tied to a pine tree.”

Illustration by Julian Rentzsch

COTTON PATCH OFFERS insight into one of Jordan’s central motivations. His theological reflections and prophetic rebukes were for his community — the rural South. Despite his doctorate, Jordan avoided academic jargon and spoke with a rough, bitter, Southern snark so that everyday people could grasp the magnitude of Christian life. “Get ready to moan and groan because of the hardships that are coming,” Jordan wrote in his translation of James 5. “Stocks and bonds are worthless” and the wages of the “workers who till your plantations and them you’ve cheated are crying out.”

Jordan wrote: “[James] seems to be assuming here that any man who’s wealthy stole it from somebody. You’ve got to get it from your laborers or from somewhere. You can’t make that much.”

Jordan’s deep commitment to an embodied, communal expression of faith shines through in his folksy vernacular. This commitment was not a filter for his theology, but an outpouring from it: God’s humanity in Christ’s incarnation is in the poor and oppressed — this is central to Jordan’s beliefs. The resurrection was not a promise of eternal life but “another form of the incarnation” and the proof that Jesus “has risen and comes home with us” in the form of the hungry, widowed, imprisoned, and oppressed.

The incarnation, Jordan reasoned, was an offense to those who wished to keep Jesus in the clouds. White Christians, who wanted a Christ they could worship without loving their neighbor, needed offending. Jordan satirized how his audience might react to a modern translation of John 1: “The Word became flesh and bought a home in our neighborhood — yeah, the black bastard, and made the price of our property go down!”

Jordan’s decision to stay in the rural South, regularly encountering white supremacists and meeting them with nonviolent resistance, perplexed many. Family members feared for Koinonia’s safety. Allies wanted Jordan to join national protests and marches. But Jordan resisted the urge to expand Koinonia’s scope. While engaged with the world around him, Jordan saw his mission as primarily for American Christians, and for the South in particular.

Jordan started his efforts among those folks because of his roots, but my suspicion is that a deep compassion for the “lost” kept him there. Christ preached a salvation for those who fed the hungry and freed the imprisoned — who could be more lost than white Christians who didn’t radically resist the evils of racial capitalism? Jordan preached universal reconciliation, believing that God would seek the lost until he “has depopulated hell.”

“God is not a celestial prison warden jangling the keys on a bunch of lifers — he’s a shepherd seeking for sheep, a woman searching for coins, a father waiting for his son,” Jordan said. Jordan said his highest joy would be to spend eternity preaching to those in hell who didn’t know God loved them. He brought the message of God’s radical love in a voice his racist neighbors might understand, so that they might accept the severity of their actions and repent. Somebody had to tell them, so why not Clarence?

WHILE HIS THEOLOGY and praxis are not formally associated with liberation theology, I believe it is the best lens for his work. Indeed, Jordan’s final decade took place while James Cone, Gustavo Gutiérrez, Leonardo Boff, and others were birthing formal liberation theologies.

The work of Cone and the rest has had time to grow, develop, and evolve with the times, and a similar growth can apply to Jordan. Black and Latin American liberation theologies, critical race theory, womanist theology, and queer liberation movements all offer helpful critiques and supplements to Jordan’s work.

Toward the end of his life, Jordan was trying to imagine what it might mean to witness to his neighbors going forward. “An integrated, Christian community was a practical vehicle through which to bear witness to a segregated society a decade ago,” Jordan told The Baptist Student in 1969. “[But] now it is too slow, too weak, not aggressive enough.”

Jordan resisted racial capitalism and violence as it manifested in his day, and we must resist it in ours as it manifests in policing and prisons, war and the preparation for war, ecological destruction in fossil fuels, and more. We must meet our neighbors without fear of getting our hands dirty. Cooperative and urban farming, mutual aid, and unionization are among the ways we can work with, not just for, the liberation of all.

Jordan would embrace this effort. He might disagree with me in some applications or appropriations of his work. But for all his stubbornness, Clarence gave of himself with humility and inspired the work I, and many others, do today. “With all the shortcomings,” Jordan wrote of his Cotton Patch translations, “I pass them on to you with the fervent hope that you may thereby be encouraged and strengthened in your life in Christ.”

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!