MAYBE YOU FIRST saw it while sitting in the waiting room of the doctor’s office — a Fox News banner update across the bottom of the screen. Or perhaps you saw the hashtag on X or Threads. Maybe you’re following the story as internet sleuths exchange theories on Reddit. Here’s what you know: There’s an SUV making its way from California to Washington, D.C., driven by a man and a woman in their 20s. They’re transporting some sort of nuclear device, and they plan to blow up the president. And, for some reason, law enforcement isn’t taking this very seriously.

It’s the story of the moment. Even though nobody has any real facts. Everyone just knows we’re collectively watching a disaster unfold.

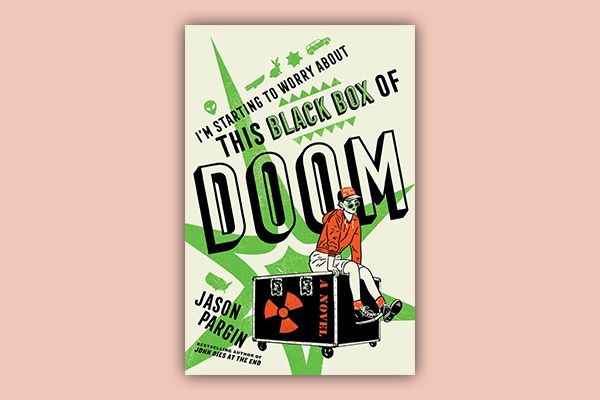

Such is the setup for Jason Pargin’s I’m Starting to Worry About this Black Box of Doom, a parable of the dangers of the information age. Pargin’s witty, incisive novel illustrates how social media has eroded our ability to trust each other.

Read the Full Article