Walter Fauntroy represents the District of Columbia in the U.S. House of Representatives and is pastor of New Bethel Baptist Church in Washington, D.C. He has long been a leading figure in the black freedom movement. Fauntroy was a close associate of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and a leader in the Southern Christian Leadership Conference founded by King.

Since entering Congress, Fauntroy has also continued his involvement in non-electoral activities. In 1981 he was arrested with a group seeking to block the opening of a toxic waste dump in a poor and primarily black county in South Carolina. In 1983 he was the primary organizer of the 20th Anniversary March on Washington for Jobs, Peace, and Freedom.

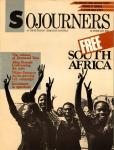

On November 21, 1984, Fauntroy, Randall Robinson, director of TransAfrica, and U.S. Civil Rights Commission member Mary Frances Berry were arrested in a sit-in at the South African embassy in Washington. That action sparked what has now become a nationwide campaign of nonviolent direct action against apartheid and U.S. policy in South Africa. On December 13, Sojourners visited Fauntroy at his congressional office to discuss the development of the Free South Africa Movement and his involvement in it.

-The Editors

Sojourners: The news of your arrest as part of a sit-in at the South African embassy came as a very pleasant Thanksgiving Day surprise to many of us. Could you tell us about the sequence of events that led to that action and the subsequent Free South Africa campaign?

Walter Fauntroy: What happened on November 21 probably had its beginning back in 1982 when Coretta Scott King talked to me about the 20th anniversary of the March on Washington and the need for a coalition of conscience like the one that had moved the nation 20 years before to deal with basic problems—segregation and discrimination—that confronted us at that time. I have been working for several years building what I call the black leadership family by pulling together the heads of about 150 national black organizations to put together a plan for our own survival, unity, and progress. I saw this 20th anniversary as a means of implementing the plan.

Our plan, announced at the beginning of the Reagan era, was to do four things. The first was to go on the defense against cuts in those programs that improve the quality of life for American people and blacks in particular. Second, going on the offense, we aimed to come up with constructive alternatives to the Reagan policies that were being advocated. Third, we planned to organize ourselves in about 115 congressional districts where blacks are more than 20 percent of the population and could influence the work of those members of Congress. And finally, we aimed to reach out in coalition with others whose interests coincide with ours.

So I began to work on putting together the 20th anniversary of the March on Washington. We pulled together not only the church, civil rights, and labor groups that organized with us in the '60s, but we expanded to include movements that have developed since that time: peace activists, environmentalists, the Hispanic movement, and the women's rights movement. We fashioned a masterful exercise of the First Amendment right to peaceful assembly to petition government for redress of grievances of about 500,000 people here.

We identified 14 pieces of legislation we resolved to work on as a coalition of conscience over the 1983-84 year. Among them was the Hawkins Community Renewal and Full Employment Act that we got passed in the House, but not in the Senate. We also worked on the Martin Luther King Holiday Bill and the Gray Amendment to ban new investments by American corporations in South Africa. We worked on those, contacting the elements of the coalition, urging them to call their members of Congress, saying, "If you can't vote for this, we can't vote for you in November."

As a result, we got the Gray Amendment passed in the House, but we failed in the Senate because the president intervened and told his Republican-controlled Senate that he did not wish to have this alteration to his policies of constructive engagement.

We took that loss but determined to work in the traditional process—the electoral process—to try to change priorities from 1985 on. So we took some of the coalition of conscience into the Rainbow Coalition working around Jesse Jackson to raise these sharp issues of domestic and international problems. But because the majority of the American people were feeling better about themselves four years after Reagan started, because they were spending borrowed money, deficit money that had been built up, Reagan won.

Clearly, there was little hope of our being able to affect policy over the next four years through the traditional means, that is, political action. The founding fathers were wise enough to recognize that in our democracy there might come times when the political process would not function for those who had legitimate grievances and could not get them addressed. So they set aside a second means of affecting public policy, and that was the First Amendment right of peaceful assembly and the right to petition government for redress of grievances. It became very clear to us that that perhaps was the option we had to take.

It had worked before at a time when most of us wanted to affect public policy on "white only" signs across the South. Then we could not do that using traditional means, because we couldn't vote. We were beaten and maimed and killed, and & our organizers brutalized for trying to get I us the vote. Faced with that, faced with the failure of the courts to address our problem across the board, we then entered First Amendment politics—what we called the politics of creative tension.

We had demonstrations; we marched; we went to jail in order to raise our issue to the level where it pricked the conscience of the body politic. And on July 2,1964, the body politic, in a bill called the Civil Rights Bill of 1964, translated what they believed into public policy and practice.

We could then move into traditional means of influencing public policy. After we got the Voting Rights Act passed, there was no need to demonstrate in the streets for Head Start programs, because we had developed political clout with new registrars to influence public decisions. We did not have to work for the Great Society programs. And we did not even have to work in the streets for the Humphrey-Hawkins Full Employment Bill or for the housing programs. Therefore, what issue should we address?

We were on the brink, on the threshold of historic polarization in the country pursuant to the elections of 1984, and the South African issue presented us a clear opportunity to reassemble a coalition of conscience around something with which most people have to agree. Then I was approached by Randall Robinson, the head of TransAfrica, what we in the black community consider black America's lobby on Africa and the Caribbean. And as I am president of the National Black Leadership Roundtable, which holds together all the heads of national black organizations, we decided to launch something.

We chose November 21 because it's a down time for the media. We had to keep rather quiet, because we would not have been allowed in the embassy if they had had any idea what we were going to do. We went in and talked about policy options in South Africa. Eleanor Holmes-Norton, who is a professor of law at Georgetown [University] and head of the EEO [Equal Employment Opportunity] Commission, left the meeting to inform demonstrators outside and the press that we were going to sit-in.

The press eventually called the ambassador at the embassy to ask how the sit-in was going. He said there was no sit-in, that we were sitting there having a very enjoyable conversation. He said, "If it weren't so funny, I'd laugh about it." When he'd finished laughing, we shook our heads and said, "Yes, we're here to stay until you call Pretoria [South Africa] and tell them we'll leave when we get four things: release of all those who have been arrested this year; release of long-term prisoners who had been legitimate leaders of the black African people in South Africa; the start of good-faith negotiations with that leadership toward dismantling apartheid and writing a new constitution; and a change in our country's policy." Well, shortly after, they arrested us and took us out of there.

To understand precisely what happened you have to know that it is our view that this country's policy of constructive engagement—which is all carrot and no stick—released South Africa to become more brutal in its four stated objectives: to destroy the liberation movement; to co-opt those leaders in South Africa they can; to repress those whom they can't co-opt; and to prepare for total warfare, both economic and military.

Encouraged by this country's constructive engagement policies, they began undeclared wars on Angola, Mozambique, and Zambia, where freedom fighters had camps and were training to conduct sabotage forays into South Africa. When the South African army invaded Angola, the United States was the only nation to veto the resolution condemning the South African government for that action. Then they bombed Mozambique into submission, and on March 16,1984, forced their government to sign a treaty with South Africa in which they agreed not to allow the liberation forces to organize and strike South Africa from there. Having stonewalled in Namibia, having gotten things under military control with the help of $23 million in purchases—that Reagan allowed—from the U.S. government, they then turned on their second objective—to co-opt those whom they could and to repress those whom they could not.

Their first repression attempt was in February when the South African students recognized that they could not prepare for violent war, but they could go into nonviolent conflict. They had demonstrations against the inferior schools in which they are trained to work in the mines or in the factories while the minority white students are trained to manage the economy and run the government. As the result of their protest, 134 were gunned down, and the students' leaders were arrested.

Then, in order to co-opt as many as they could, the South African government came up with a proposal for a new form of government that would create a parliament for the 1.3 million "coloreds," or mixed-race people, and 800,000 Asians, but nothing for the black 72 percent of the population. When mixed-race leaders and Asian community leaders rejected that proposal and began organizing a boycott of the election, they turned out to be very successful. Eighty percent of the mixed-race people refused to vote; 70 percent of the Asians did not turn out. And as a result, again, the government arrested all of the leaders and said that if they raised their heads by any means of protest they would be arrested without charge and detained without trial.

Then black labor union leaders and the black student leaders who were still out and the black township leaders in outrage decided, though we cannot fight, while America is voting on Reagan, we will be voting with our feet. We will not go to work. A million of them stayed away November 5 and 6 from the factories, the mines, and the fields. The heartland of South Africa, the Transvaal province, was brought to a standstill. In response, the troops that had been deployed along the border, which were now no longer needed, were sent into the black townships arresting without charge and without trial every leader who had been identified. They ransacked the labor union office and imprisoned their leaders.

In short, Thanksgiving Day arrived, and it was clear that we had to do something here in the United States. People like me simply said enough is enough. If your policy now is to take any nonviolent leaders—be they black, mixed-race, or Asian—and imprison them without charge, take us too. So we offered ourselves, and you've seen the groundswell of members of Congress, national leaders, black and white together, the labor movement, and others, all saying take us now, take us also. And the movement has just begun; we're going to go through several more phases.

Our purpose during this period is to educate the American people to the fact that apartheid in South Africa is not simply a system of social segregation that is repugnant to all decent thinking human beings, but, more important, it is a system of political domination for the purpose of economic exploitation. It is a system of labor control by which black South Africans are made available to the world as the cheapest labor source that can be found.

Those who have corporations and products to be made or money to be invested go there, where the average yield or return on a manufacturing investment is 25 percent, while around the world the average return is 18 percent. They come there to work the mines where the average return is 18 percent on an investment, while the average around the world is 12.6 percent.

George Wallace, the governor of Alabama, sent word to me that he supports the Free South Africa Movement. Why? Because at the port of Mobile, Alabama, where they build ships, they are importing steel from South Africa, while up the road in Birmingham, Alabama, they are closing down steel mills. They are importing coal from South Africa for the electric companies of the South, when up the road at Tuxedo Junction they have closed down coal mines in which there is the same kind of coal.

The system of apartheid and labor control, the passbooks and denial of citizenship rights, and the relegation of blacks to only 13 percent of the land—the most barren and unproductive land in the country—all operate to provide people who will work for $80 a month in a mine or $140 a month in a factory. If you send ambassadors and representatives to consulates around the world where economic activity is vibrant—whether it is in Houston or Mobile or Boston or New York or Los Angeles—and appeal to businesses that are operating there to relocate their facilities to South Africa, then no job is safe anywhere in the world so long as South Africa is not free.

You have set off a spark in this country that is enormous. Did you expect the breadth and depth of response; are you surprised by it? How do you feel about the response and what is your sense about why it has been so widespread?

Of course I am delighted by it. What surprised me was the sense of frustration and anxiety on the part of people who are concerned about environmental issues, about peace, about the economy, who voted against Reagan out of a depth of understanding of the way he was moving the country, and who need some beginning point for awakening the American people to what is going on.

What also has surprised me has been the extent to which the labor movement responded; the leaders of that movement offered themselves for arrest at the South African embassy. Steel workers in Birmingham had been told they lost their jobs because of affirmative action and Equal Employment Opportunity. The workers are now saying that is not the issue; it is the South Africans getting into our pockets.

I am determined we are going to win this. We are going to get into the pockets of those who are getting into our pockets by a variety of means, and we are going to win.

You mentioned earlier that this is a beginning in terms of the Free South Africa Movement and several phases are to come. Would you elaborate on that?

First we must get the consciousness raised, so people begin to ask why leaders like that are going to jail. Then people are going to start asking what they can do.

Well, everybody can't get arrested; we don't want but one or two a day to get arrested. What you can do is go to any bank that's selling Krugerrands [South African coins], which make up 50 percent of all the exports to come out of South Africa, and tell them "either you stop selling them or we will withdraw our money from your bank." The result will be that within a few months you will see signs in banks around this country: "We do not sell Krugerrands." That's going to hit them in the pocket in South Africa.

We are going to identify some multi-national corporations that may be based here that are exploiting South Africa's cheap labor system and are making good returns. We are going to ask not only that we selectively patronize them, but we will ask others to join us—those of conscience in England, in France, in West Germany, in the Netherlands, and from everywhere else where people want to free the world of this guaranteed cheap labor that is a threat to anybody who wants to work elsewhere. And I think that any of the multinationals in South Africa for that purpose are going to think about disinvestment.

We are going to continue to press cities that have pension funds to withdraw them from companies investing in South Africa. I think as we raise the issue of the eight billion dollars invested by stockholders in this country, individuals will feel pressure to disinvest.

I think those pressures helped move a president from saying, "I am not going to meet with Mr. Tutu" to then meeting with him, and then saying, "I am not going to change my policies" and coming out the next day and telling the country a lie: "I got 11 people released," a bold misrepresentation of whose political pressure actually did get them released. And then after 35 Republicans who are conservative say, "Look, it's us who are in trouble, so you'd better change." Then Reagan says, "Well, you know I said yesterday that my policies were working. I must admit today that constructive engagement, quiet diplomacy, doesn't always work. You have to judge your allies, and so I am judging today. Apartheid is bad; please change it." That's what he's saying today.

Before long he'll be saying he thinks it's a good idea to pass the Gray Amendment because Mr. Heinz, his blocker in the Senate from Pennsylvania, now has pressure from steelworkers in Pittsburgh, and Homestead, and Johnstown, workers who had thought that South Africa was the colored people's problem, who now understand that their jobs went there.

What I now predict is that just as 1865 was the year that came time to end the system of slavery in America, just as 1945 became the time to end the Nazi tyranny, 1985 will be the year that will end apartheid in South Africa.

You mentioned the divestment of U.S. corporations that do business there as one of the goals. A lot of people say that the divestment strategy won't work, that it doesn't have the leverage to move the South African government. The other line of attack is that all it does is take away jobs from black South Africans and make them more miserable than they already are.

I am sure they said that to William Lloyd Garrison: "I know you want to abolish slavery, but what would these people do if we didn't feed them, didn't provide them with meaningful work. They're happy; hear them singing in the fields." It's the same thing that I am sure they said to the founding fathers here. "It is better to pay the tax than to be without their trade. They made this country. So taxation without representation is not too bad when you think about it." And so they're saying that about South Africa now.

But what are the facts? First of all, divestment by this country alone will not work, although we are South Africa's number-one trading partner. A change in South Africa will only happen when people of conscience around the world decide this is a threat to all of us. The pressure will come, and that's why we will be internationalizing the movement very soon. So it can't work alone, but we are building a coalition of conscience—nationwide and internationally based on not only moral outrage but on self-interest.

Second, the United States has been subjected to a massive propaganda campaign over the last four or five years by the South African government because we are its number-one trading partner. A lot of the investment of capital—some $3.8 billion in direct loans from banks—comes from Chase Manhattan, Citicorp, First Boston, Continental Illinois, Morgan Guaranty Trust, and Ritter-Peabody. All these banks are investing and South Africa doesn't want them to feel the pressure of "extremists" who have been saying South Africa is mean and bad. So the government there has suggested that the people are happy.

They have begun bringing nice little choirs of South African children to sing "Jesus loves me" on television. That's a very interesting attack but it won't work.

You are a member of the Congress and a minister of the gospel. What word to Christians do you have? Why should Christians see this as an issue they should become involved in?

It is a matter of personal salvation. When this warfare of life is over, and all of us have got to go—we can't stay here always—the Lord is not going to ask us how many songs we sang in church, how often we went to church, whether we wore designer clothes when we went, whether we rode around in a Mercedes. But the question will be, when I was hungry did you feed me? When I was thirsty did you give me something to drink? When I was sick and imprisoned in South Africa did you come to see about me? And the Lord's answer to us will be, inasmuch as you didn't join the Free South Africa Movement in 1985 when I was trying to declare good news to 25 million poor exploited people, you did it not unto me.

Some would ask why you are going out and violating the laws since you are a man who makes laws. How can you make laws and break laws at the same time?

Because I am fortunate enough to live in a country that allows, by its First Amendment, the right of any citizen to peacefully assemble and petition and, in fact, to break a law so long as he is prepared to suffer the consequences. We broke the law; we are prepared to suffer the consequences.

But the South African embassy knows that. They will not put me on trial because people would be educated by what I would set as my defense.

After I had been arrested, I went into the cell block and some angry young black men asked me what in the world I was doing here for some damned South Africans when people need jobs in the United States. And then I sat down with them for about an hour and explained that there are no jobs here because cars that used to be made here, steel that used to be made here, rubber that used to be made here, is now made there. And they said, "I'm ready to join the movement when I come out." The South African government didn't want that explanation to be made in a trial. And it's not my fault that they won't put me on trial for having broken the law.

As I told President [Lyndon] Johnson at the critical point in the [civil rights] movement, "The Lord is my shepherd. God is not a Democrat; he is not a Republican; he is not a conservative; he is not a liberal; he is not black or white; God is the reward of them that diligently seek him." My responsibility as a minister is to declare good news to the poor. In fact, I am anointed—as is every Christian—to do that.

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!