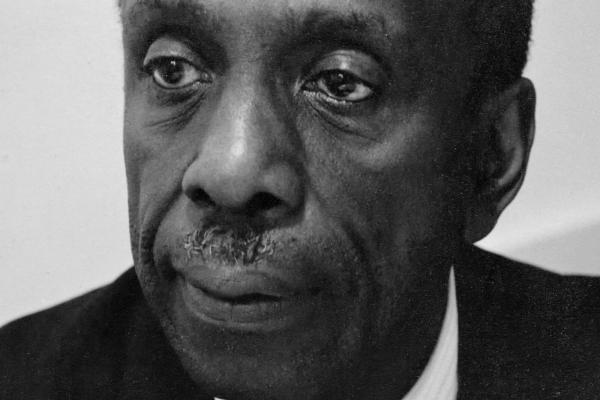

ONE OF THE MOST influential figures in the African-American civil rights movement did not march, organize, or speak at mass rallies. Mystic Howard Thurman found spiritual revelation in nature, championed the use of dance, theater, and nontraditional music in worship, and incorporated silence in his sermons. But his books, preaching, and teaching provided vital philosophical and spiritual underpinnings for the nonviolent resistance methods championed by Martin Luther King Jr. and other civil rights leaders.

Backs Against the Wall: The Howard Thurman Story, airing on PBS in February, is a documentary by Martin Doblmeier, the award-winning creator of films on faith including An American Conscience, Chaplains, and Bonhoeffer. In this rich, one-hour portrait of Thurman, civil rights leaders Jesse Jackson Sr., Rep. John Lewis, and others—as well as scholars such as Alton B. Pollard III, Walter Earl Fluker, Luther E. Smith, and Lerita Coleman Brown—offer insights on Thurman’s life, legacy, and the dynamic tension between contemplation and social justice.

The film’s title is from Thurman’s book Jesus and the Disinherited , published in 1949—said to have been carried by King and often cited by other civil rights leaders. Thurman wrote: “The masses of [people] live with their backs constantly against the wall. They are the poor, the disinherited, the dispossessed. What does our religion say to them?”

Thurman’s lifelong engagement with this question produced wisdom as vital for our day as it was for his.

Read the Full Article