Share As A Gift

Share a paywall-free link to this article.

This feature is only available for subscribers.

Start your subscription for as low as $4.95. Already a subscriber?

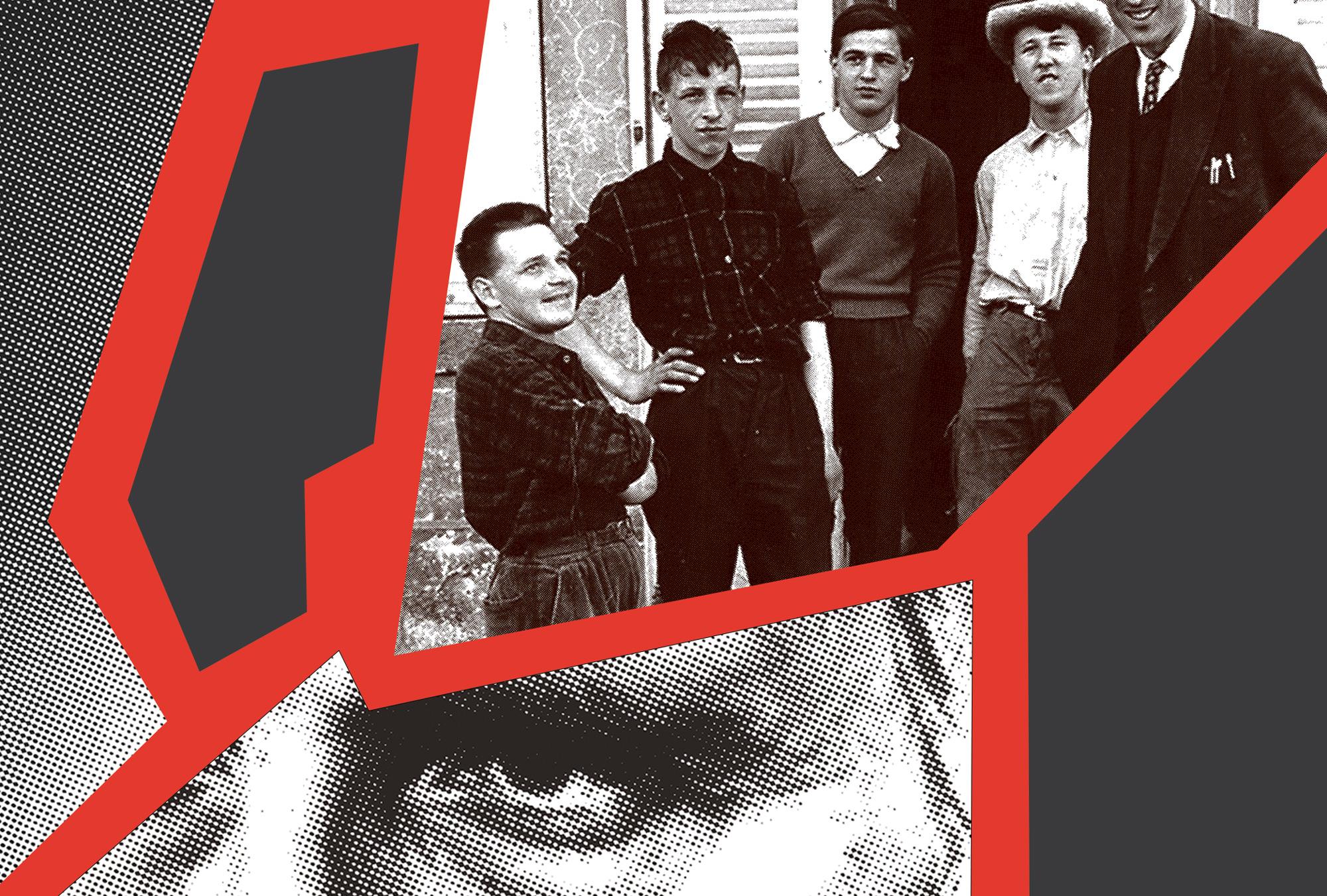

Illustration by Mark Lucien Harris / Archival photos from L'Arche International

THIS IS ONE way to tell the founding story of L’Arche:

The main character is a sailor-turned-ethicist named Jean Vanier. The son of the governor general of Canada, he was, as his biographer Anne-Sophie Constant wrote, “a child of privilege, he had danced with princesses, dined with politicians and philosophers, and circled the world twice.”

As the story goes, Vanier gave all that up in 1964 when his spiritual mentor, Thomas Philippe, a Dominican priest, took him on a tour of the psychiatric facility where Philippe was a chaplain. There, Vanier discovered, as he put it, “an immense world of pain.” This is not an exaggeration: At the time, asylums, which were notorious for overcrowding and abuse, functioned more as prisons than treatment centers. Inside these walls, Vanier heard an invitation — from Jesus and the men with intellectual disabilities — to do something.

So Vanier bought a broken-down house in Trosly, France, and invited two men from the mental institution to live with him. He named the home “L’Arche,” French for “The Ark,” a biblical symbol of protection in a storm-tossed world. Vanier traveled around the globe to tell the story of their life together, and soon L’Arche communities sprouted up in Canada, India, Australia, Haiti, and beyond — a constellation of communities where adults with and without intellectual disabilities have aspired to live, work, pray, and play together as equals. L’Arche became integral to the movement for the deinstitutionalization of people with intellectual disabilities, and Vanier became a best-selling Christian writer and hero to all of us looking to practice a faith that prioritized those on the margins.

When he was introduced to give lectures, Vanier often said, “I feel uncomfortable when people say nice things about me.” Yet the world had lots of nice things to say, bestowing upon Vanier countless awards, including the French Legion of Honor, the Companion of the Order of Canada, and the Templeton Prize. But for me, a certain 2010 accolade feels the most poignant: Astrophysicist C.J. Krieger discovered an asteroid and named it after Vanier. Vanier is above us; Vanier spins on a different celestial plane than the rest of us.

Before he died, Vanier was often called a living saint. Upon his death in 2019, Pope Francis sent his sympathies, asking Jesus to welcome Vanier into heaven as his faithful servant. It’s the type of eulogizing that you expect for someone who saw beauty and divinity where others saw shame and destitution.

It’s an inspiring story that changed thousands of lives: At the time of Vanier’s death, there were 147 L’Arche communities in 37 countries, home to approximately 10,000 people with intellectual disabilities. The protagonist of the story also saved my faith, showing me how Christianity is capable of destabilizing dangerous institutions, rocking the boat, building new arks.

Unfortunately, it’s a bad story.

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!