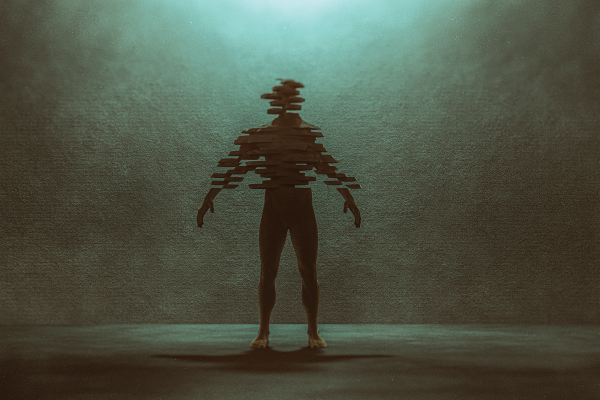

IN MY FIRST SEMESTER of divinity school, I experienced a spiritual crisis. For months, I woke every night at 3 a.m., plagued by unanswerable questions on life’s meaning, God’s silence, suffering, and human nature. At the time, I felt alone, but now, years on the other side of it, I see the healing that emerged from my “dark night of the soul.”

While the phrase “dark night of the soul” has seeped into secular parlance, it is specifically drawn from the Christian contemplative tradition. St. John of the Cross, a 16th-century Carmelite monk and reformer, wrote a theological commentary and a poem, both titled “The Dark Night of the Soul,” about good darkness, contemplation, and the journey of faith. These works emerged after John’s unjust imprisonment in a monastery, where he endured physical violence and extreme deprivation. There, John discovered the richness of the “dark night” for illumination and purification. Barbara Brown Taylor, author of Learning to Walk in the Dark,writes, “For [John], the dark night is a love story, full of the painful joy of seeking the most elusive lover of all.” While the dark night may feel like “oblivion,” John contends that “The more darkness it brings ... the more light it sheds.”

Read the Full Article