Share As A Gift

Share a paywall-free link to this article.

This feature is only available for subscribers.

Start your subscription for as low as $4.95. Already a subscriber?

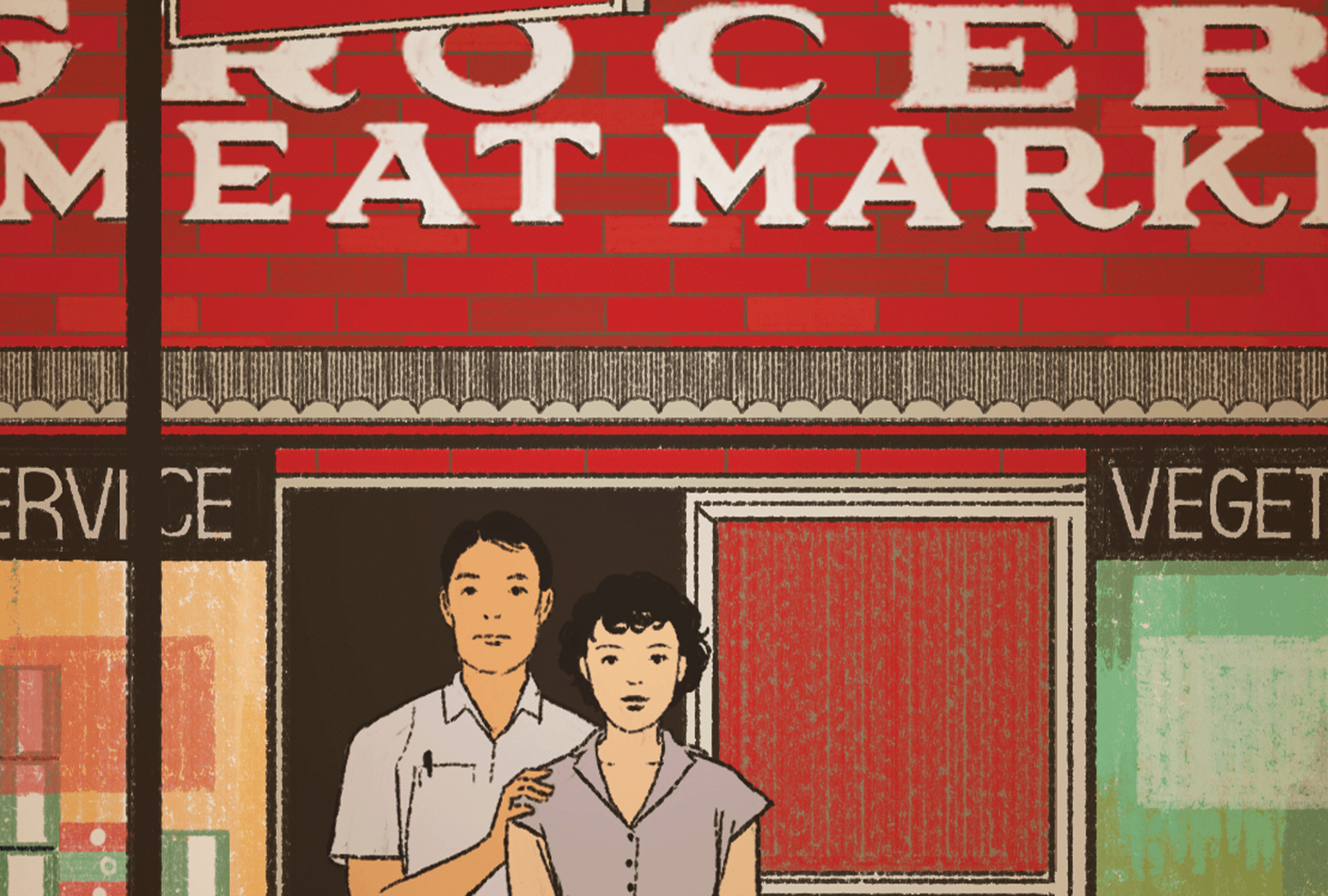

Illustrations by Julia Kuo

TO CROSS THE border into Lesotho — a landlocked, mountainous country surrounded entirely by South Africa — my friends and I rented a 4x4 and drove up the icy Sani Pass. We switchbacked up one of the most dangerous roads in the world and almost skidded off the cliff.

Slightly shaken but unscathed, we experienced time stretching as we drove through the pastoral city of Mokhotlong, dotted with thatch-roofed mud-and-stone huts. Herds of sheep, in no hurry to make way, blocked the dirt road.

We walked along the deserted street, admiring handicrafts at a rug shop before popping into a grocery store. I was surprised when a Chinese couple greeted us from behind the counter with a warm, “Ni hao.” As my friends and I spoke with them in rudimentary Mandarin (four of us were Chinese American, the fifth was white American), I learned that they had been living in Mokhotlong for many years, raising a family while running the store. We shared a laugh about the unlikelihood of Chinese people finding one another in these hinterlands and, after buying a couple of sodas, went on our way.

Down the road, we discovered another grocery store, staffed by a Chinese couple from a different province in China. What a wild fluke, I thought, that such an isolated town would have two Chinese-owned markets! I soon learned that it wasn’t a fluke at all — Chinese people are present in virtually every nation in Africa, whether as contracted laborers or as informal migrants. Since July 2008, when I visited Lesotho while living in South Africa for two months, the Chinese population in Africa has increased to more than 1 million, including large populations in South Africa, Madagascar, and Zambia but also scattered throughout smaller communities in South Sudan, Togo, and Senegal.

The awe of meeting Chinese people in rural Africa prompted me to examine my family’s migration story and my sense of otherness in the U.S. My parents left Hong Kong to come to the U.S. for college, planting roots here for the freedom and opportunities that didn’t exist back home. Shortly before I was born, they became Christians through a Chinese immigrant church in the Bay Area. When I was 3 years old, we resettled near the University of Iowa, where my dad worked as a cardiologist.

While my parents were members of a small but vibrant Chinese church, by junior high I started attending a large, white, evangelical church where I could fully understand the English language worship service and have peers my age. Bathed in a white-dominant environment both at school and at church, I subconsciously believed that my differences made me inferior and that white male theologians were the arbiters of true Christianity — after all, they were the only people preaching or quoted from the pulpit. This led me to “the misguided belief,” as Grace Ji-Sun Kim writes, “that white knowledge, theology, and spirituality were far greater than anything we had ever possessed.”

As I started wrestling with doubts during and after college, I languished in self-recrimination. I didn’t have the language or assertiveness to critique the overconfident dogmatism or the white normativity of the American evangelical church. If I didn’t fit the mold, I must be the problem. I never fully belonged in Iowa, despite chameleon-level assimilation, or in the church, which I considered my second home.

I was searching for purpose amid my privileged otherness. A career in medicine seemed one way to alleviate suffering and be useful in underserved settings — which is how I ended up on a medical student research fellowship in a South African hospital filled with patients dying from drug-resistant tuberculosis and HIV/AIDS. I was struck by the absence of barriers between faith, work, and activism, such as when dissidents at an academic conference on tuberculosis held protest signs against government health policies, or when hospital nurses opened each day with a morning hymn. And although I only spent one weekend in Lesotho, the encounters with the Chinese shopkeepers stayed with me as well.

After returning to the United States, I’d occasionally relay the story of the Mokhotlong grocers. Initially, reactions were a mix of surprise and delight: “Wow, Chinese people are everywhere!” my companions of various ethnicities would exclaim, smiling in awe. As years passed, though, there arose a harder edge to the comments about the Chinese diaspora, especially from certain white Americans, a tone of resentment and suspicion peppering the words: “Chinese people are everywhere.” How could we be everywhere yet still struggle to belong?

FROM OUR EARLIEST days in the United States, Asian Americans have been scapegoated as disease vectors, accused of taking jobs from white Americans, and targeted with brutality. Driven out of Western towns by vicious mobs, excluded from citizenship, murdered in one of the largest mass lynchings in U.S. history, worked to death while building the transcontinental railroad, and incarcerated solely based on ethnicity, Asian Americans still suffer racially motivated violence today. The residue of this long legacy of persecution coats our presence in the United States.

But our existence in the U.S. is not a straightforward story of subjugation. Unlike African Americans, many of whose ancestors were kidnapped and enslaved, most Asian American immigrants have at least a modicum of choice, fleeing political repression, poverty, or war, while others, as in my family’s case, come seeking educational or economic opportunities. Many Asian Americans have enjoyed advantages that other minoritized groups have historically not had. (Granted, the U.S. often played a role in destabilizing our homelands through armed conflict. As Korean American poet Cathy Park Hong writes in Minor Feelings: An Asian American Reckoning, “I am here because you vivisected my ancestral country in two. ... Don’t talk to me about gratitude.”)

In Asian Americans and the Spirit of Racial Capitalism, Jonathan Tran disrupts oversimplified narratives of victims and oppressors, righteous and unrighteous, and Black-white racial dualism. Through a case study of Chinese American grocers who served a Black sharecropper clientele in the Mississippi Delta for a century after Reconstruction, Tran illustrates ways these grocers exploited a need in the system. They became financially stable while profiting from poor Black farmers. By slotting into this need, the Delta Chinese were participating in and perpetuating anti-Black structures (what Tran calls racial capitalist aftermarkets) established by the white elites, structures designed to keep Black people destitute through debt peonage, voter suppression, and drastic underfunding of public goods for their communities.

Over time, many Delta Chinese grocers and their families converted to Christianity, recognizing that church membership lent them greater acceptability in the eyes of the ruling whites and educational opportunities via Southern Baptist-sponsored schools for Chinese children. Rather than creating solidarity with their Black customers, who were often Christian, the strain of Christianity many Delta Chinese assimilated into was more concerned with proximity to whiteness and the veneer of legitimacy it conferred. White Baptist Christianity claimed material success as a sign of God’s favor, thus consecrating the Delta Chinese’s business model of hard work and financial gain without compelling them to ask tough questions about their responsibilities toward their Black neighbors.

THE GROCERS I met in Lesotho left behind their homeland, loved ones, language, food, and cultural norms to try to make a living and, in doing so, create better lives for their families. On the surface, this seems reasonable, even admirable. Yet were the Mokhotlong Chinese grocers just like the Delta Chinese grocers? Is this racial capitalism on a global scale?

I asked Tran whether it’s fair to critique the Mokhotlong grocers or the Delta Chinese grocers for having opportunistic economic relationships with Africans or with Black Americans. He points out that if we are comparing this behavior to business as usual — that is, the norms of global capitalism — then it isn’t particularly predatory. In fact, these critiques of the Chinese are frankly racist when not equally applied to white Americans and Europeans, who have been profiting from capitalist structures for centuries.

However, Tran explained, “You know it’s bad by comparing it to an alternative economy. Divine economy is the very opposite of exploiting opportunities. Rather, it seeks to repair them.”

Tran pointed out, “There’s no doctrine in Christian theology that isn’t wishful thinking. Theology, by its nature, is wishful. It believes in God when there’s evidence to the contrary. It believes that God is good when there’s evidence to the contrary. That’s why we’re eschatological beings; we think in terms of God’s redemption of things.”

Theologian David Chao, director of Princeton Theological Seminary’s Center for Asian American Christianity, argues that a significant issue with the faith espoused by the Delta Chinese in Tran’s case study remains relevant to evangelicals today. “When Asian American Christians don’t have a theology of their social embodied-ness, including racialization, political economy, and material histories, then none of this enters into what the gospel is, what loving our neighbors is, what our Christian practice of discipleship looks like. Because the Delta Chinese did not limn economic realities as part of their Christian faith, they had no religious or spiritual resources to call out any economic issues, exploitation being foremost,” he explained.

Chao hopes all Christians will take seriously, as part of our Christian identity, decisions about where we live and work and send our kids to school and the material consequences of these decisions. “Then and only then can we resist systems of capitalist exploitation,” he said.

THE FAITH OF my childhood — both that of the Chinese immigrant church and the white evangelical church — was much like the Southern Baptist Christianity the Delta Chinese adopted. It was a faith of personal piety and respectability, a faith that declared success to be a manifestation of God’s esteem. As I became more cognizant of both my privilege and my marginality, following Jesus felt hollow if it did not involve laying down that privilege. A faith that didn’t speak into the margins was morally anemic. Yet the evangelical church culture I’d grown up in was concerned almost exclusively with saving souls. The carbon copy of Western Christianity I was supposed to clothe myself in didn’t fit, and my soul was starved.

As much as I longed for belonging that day I drove up to Lesotho, I also yearned for justice — economic, social, political, interpersonal — a restoration of right relationship among God’s children. Working alongside ordinary South Africans, I witnessed their faith in the early aftermath of the apartheid regime despite continued impoverishment and their president’s HIV/AIDS denialism. The Black South Africans I met practiced a different flavor of Christianity than what I had known growing up, one that permeated all spheres of life and gave them the mettle to face their trials. They had an awareness of the power dynamics and material realities of life, as exemplified in Archbishop Desmond Tutu’s proclamation that “if you are neutral in situations of injustice, you have chosen the side of the oppressor.”

In later years, I similarly learned from Black Americans whose faith had historically equipped them to resist ongoing injustice. This is not to glorify Black expressions of Christianity as more authentic or reduce them to a monolithic entity; rather, I noticed in the faith of Black Americans and Black South Africans a sense of God’s presence as immediate; God’s Word on the side of the oppressed.

Although there have been important pockets of Asian American activism throughout U.S. history, including notable figures such as Grace Lee Boggs, Larry Itliong, and Yuri Kochiyama, Asian American Christians broadly speaking — along with the white evangelical church — have not considered marginality something to be embraced. We’ve been caught up in the American Dream: If we keep our heads down and assimilate, playing down our racial trauma, we’re promised acceptance, wealth, and recognition. We too often journey through life undiscipled in matters of race and economics. We need a theology robust enough to engage with the dual truths of our status as survivors of racial hatred and our complicity in racial capitalism.

There is a daily choice that all of us, regardless of race or ethnicity, must make. The flawed logic of racial caste puts Asian Americans in an “in-between” place that sharpens the contours of that choice: Do we walk toward power and profit, or toward marginality? “The life Jesus invites,” Tran writes, “involves an ellipse between two points, dispossession and joy ... Joy without dispossession is escapist. Dispossession without joy is sadist. The two together order Christian life.”

When I left the central places of church and society and went to the margins seeking corporate justice, I experienced solidarity and, with it, joy. When I swayed to the sonorous hymns of the nurses at morning work meetings and danced among ululating women, incandescent with rage at a rally against sexual assault in a South African township, I didn’t fit in, but I belonged. Over the years, as I’ve gathered my church community to write letters to incarcerated pen pals or opened our home to Afghan refugees or marched on Boston streets protesting immigration bans, it’s that joyful communion with others that sustains me.

We don’t have to leave our homes to embrace marginality. Each day asks us: Will we choose the wide, comfortable path of upward mobility, or will we follow Jesus in eschewing centrality and privilege and find a place where we truly belong?

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!