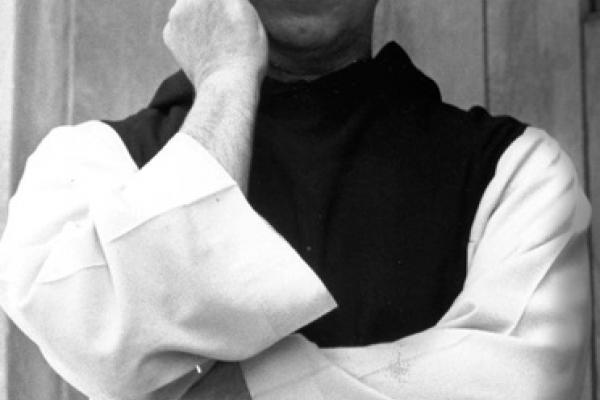

WHILE NOT HERE in person for the celebration of his 100 birthday on Jan. 31, Thomas Merton is certainly present in spirit through the extraordinary number of volumes about and even by him being issued to mark the anniversary—a splendid opportunity for readers to acquaint or reacquaint themselves with the monk often considered the most significant American Catholic writer of the past century.

Perhaps the best place to start is Messengers of Hope: Reflections in Honor of Thomas Merton, edited by Gray Henry and Jonathan Montaldo (Fons Vitae), a collection of more than 100 reflections by monks and activists, scholars, filmmakers, and poets, and Christian, Jewish, and Buddhist practitioners on the significance of Merton for their own lives. Some of the contributors are well known—Joan Chittister, John Dear, Jim Forest, James Martin, Richard Rohr, Huston Smith; others are well known in Merton circles; some are younger voices who one day may become well known but already have valuable insights as to how Merton continues to speak to the needs and hopes of the contemporary world. This is a rich compendium of personal stories that is a delight to dip into or to read straight through.

Read the Full Article