“WHY AM I here?” The question echoed in my head as it had on countless prior occasions. It seems that I cannot participate in a meeting or conference about Christian community development, social justice, or racial reconciliation without the question emerging at least once. As an African American woman, I am frequently reminded that these spaces are not my home. I am an outlier: I am neither White nor male, and I don’t fit neatly into any of the typical Protestant boxes. I am too evangelical to be mainline, too mainline to be fully historical Black church, and too historical Black church to be evangelical. Sometimes I even feel too interfaith to be Christian. I am often alone in a room full of people—the only woman of color and even the only African American woman. The conversations in these spaces are often overtly patriarchal, dismissing women’s experiences and expertise. These groups think diversity is achieved if they include men of color and White women, both of whom make pronouncements about race and gender that are assumed to capture everyone’s experiences but that exclude those of women of color. I am often forced into the position of being the “Yes, but” voice. It is soul-wearying. And yet I—we—stay.

In the past two decades, racial reconciliation has emerged as an increasingly popular topic of academic discourse in the United States and South Africa. An inherently practical discipline, the field of reconciliation studies was birthed out of the experiences of evangelical Christian ministers and laypersons whose quotidian experiences crossed traditional boundaries of race and ethnicity within the church. In the United States, the racial reconciliation movement has strong roots in evangelical church and parachurch organizations. However, because of the emphasis upon male headship and female submission among evangelicals, men have dominated the movement and the literature.

In the United States, consequently, reconciliation has been largely framed as a movement aimed at obliterating racial barriers between African American and White men. With few exceptions, women’s voices and perspectives are largely absent. The result of this exclusively male gaze is a body of literature that examines race as a singular construct, ignoring the intersections between race, gender, and sexuality.

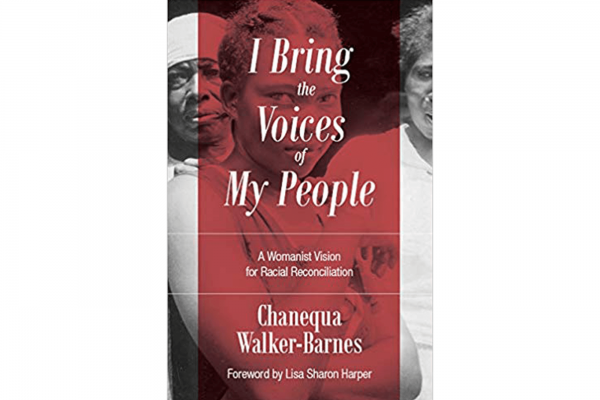

Reprinted with permission from Eerdmans.

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!