ROSE MARIE BERGER doesn’t know it yet, but through her tour-de-force poems in Bending the Arch, she has become a holy woman of many nations. Among my own people, she would be called one of the alikchi, a sacred healer, a doctor of the people, a woman who can restore balance to lives that have been shattered. She does this through the strong medicine of words.

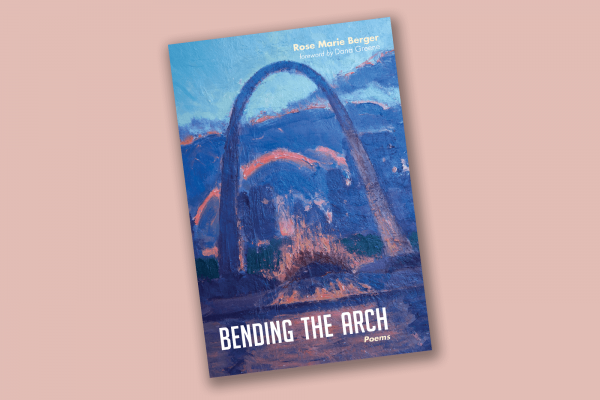

Berger, poetry editor and a columnist for Sojourners, describes Bending the Arch as “ethnopoetic documentary poetry.” “Ethno” because it speaks with the accents of a dozen different cultures: European settlers, Chinese miners, Native American leaders. “Poetic” because it uses a cat’s cradle of language from different moments, people, and realities. “Documentary” because it covers a vast scope of America’s manifest destiny history, symbolized by the Gateway Arch in St. Louis, which is depicted on its cover. All these are contained in layers of history, one on top of another, until the spiritual sediment of Berger’s meaning begins to become clear.

Consequently, you don’t read her poetry, you engage it. Bending the Arch is an encounter that requires something of the reader. It provokes. It reveals. It imagines. It asks for full attention, deep reflection, and emotional response. This poetry does not leave you alone but pulls you in, looking for more and more understanding as the layers of meaning begin to coalesce into a narrative of human triumph and tragedy. You cannot remain neutral to this experience: You must walk away or confront the reality.

If you stay as this poetry weaves threads of perception from different cultures, you will soon make a discovery. There is a hidden healing in Bending the Arch: a medicine woman’s wisdom in locating sources of pain and her skill in trying to alleviate it. For all the stories of struggle in these poems and realizations of missed chances and arrogant expansionism, there is a clear hint of hope, a reconciliation that is always at the fingertips of possibility. Many nations Berger gathers into an epic memory.

“In the end,” she writes, “it is the fact of the arch / not the myth of the arch / that stands ... In the end there is only / land world and light world / and us—a thin muscular word / stretched between.” In this intricate summation of a historical experience, Berger connects us, all of us. She reaches back through time and space, through our story. She draws out the poison. She puts her hand on the hurt. She breathes new life into old memories. She makes the hidden seen.

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!