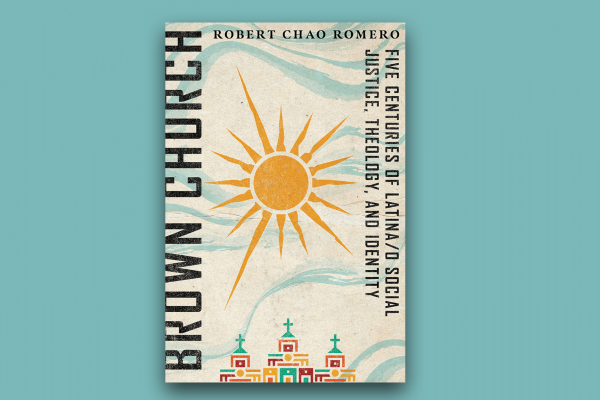

AS A LATINA, I waited with eager anticipation for the publication of Robert Chao Romero’s Brown Church: Five Centuries of Latina/o Social Justice, Theology, and Identity . As a historian, Romero is the best person to take us through the history of the Latin American church, and he tells it truly, not wishing to shield the reader from the horrors of colonization. He begins with the exploitation and conversion “by the sword” that began under the rule of the Spanish conquistadores, who brought to the Americas their Roman Catholic faith—along with their hunger for gold and other resources. Early Catholic missionaries such as Friar Antonio de Montesinos and Bartolomé de las Casas sought to divorce the faith from the Spanish colonial project and condemned the latter with courage and fervor.

It is worthwhile to note that Romero brings his readers all the way to the present, introducing them to living Latinx theologians and their work. For many readers, his chapter on “Recent Social Justice Theologies of U.S. Latinas/os” will be a great resource for delving deeper into the works of living Latinx scholars and practical theologians. While the book heavily features male scholars and theologians, it was heartening to see this section highlight Mujerista theology and the work of Latinas doing theology—women such as Elizabeth Conde-Frazier, Sandra Maria Van Opstal, Noemi Vega Quiñones, and Zaida Maldonado Pérez.

Romero acknowledges the racial hierarchy instituted under Spanish rule that still governs Latin America today, but he makes a bold statement early on in the book: “Brown Christians reject the racist legacy of Latin America in all its manifestations.” This statement may be aspirational—it is not a lived reality in most Latinx Christian communities and immigrant churches. In fact, the book itself, while called Brown Church, specifically excludes Indigenous and Afro-Latinx theologians while asserting that the term “Brown Church” includes them. A better title for this work might have been The Mestizo/a Church, since nearly every hero of the book is a Mestizo/a.

I would have loved to see Romero highlight the faith of Indigenous people prior to colonization as well as afterward—there is a rich tradition of Indigenous spirituality in the Americas that also deserves recognition. There’s also a growing number of Afro-Latinx theologians and pastors using their voices to teach the scriptures from their perspectives and emphasize the erasure of their communities from Latinx narratives.

Overall, I greatly enjoyed Romero’s book and would highly recommend it. For those of us of Latinx background or descent, it offers an affirmation that Latinx church history is church history. That, in itself, is a gift: It dignifies the faith of those who have historically lived on the margins and often have been told to accept Eurocentric theologies as the only acceptable interpretations of the Bible; it offers to the church the gift of seeing scripture and theology through our eyes.

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!