Share As A Gift

Share a paywall-free link to this article.

This feature is only available for subscribers.

Start your subscription for as low as $4.95. Already a subscriber?

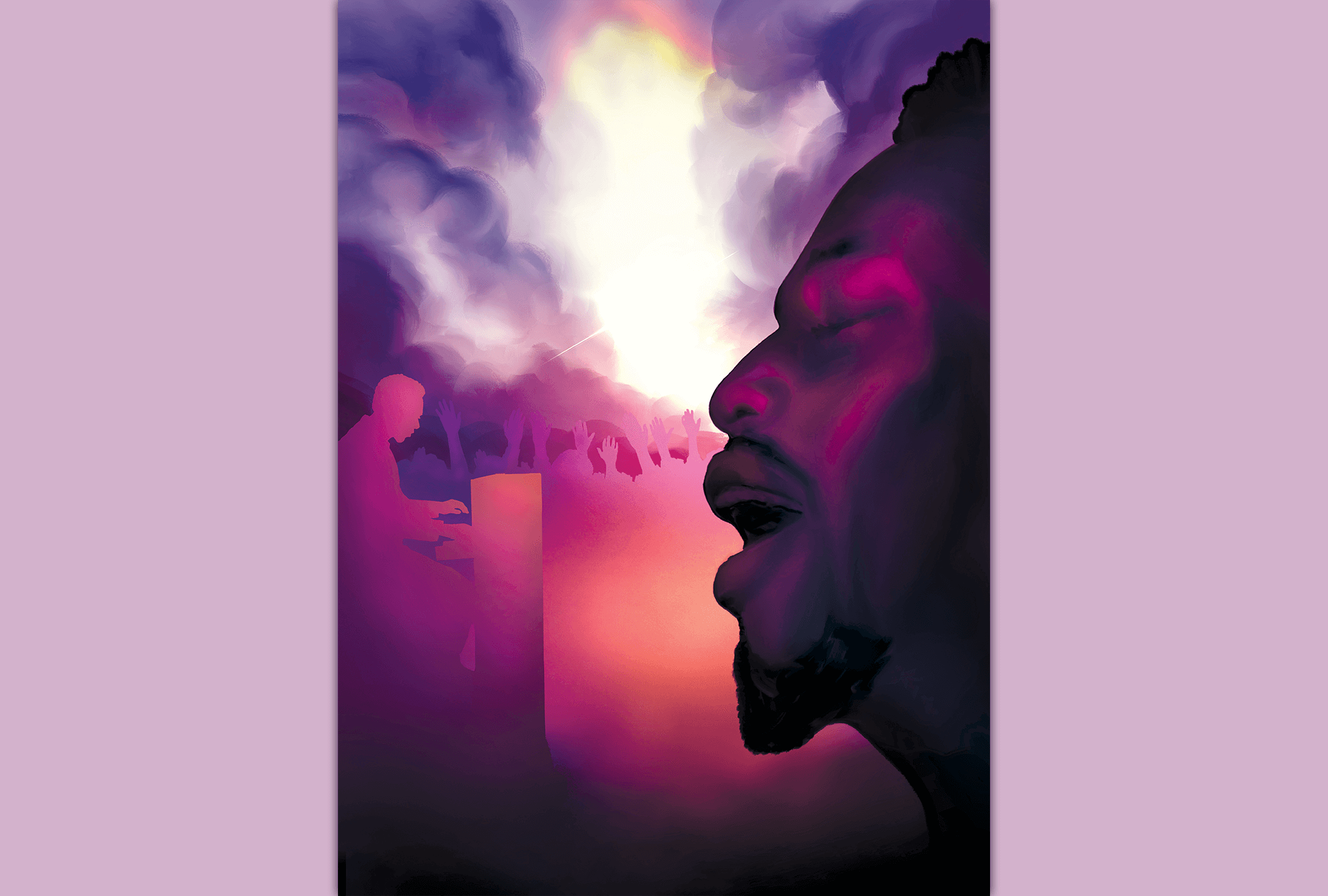

AFTER COLLEGE, I served as the musical arranger and pianist for a play based on the life of Amanda Berry Smith, a 19th-century Black woman evangelist who traveled the country and world preaching and singing. Born enslaved, she sang church hymns and spirituals. In the play, as in life, the spirituals contextualized Smith’s faith while subverting the power structures that undermined everything she was and was called to be. Fatigued by rejection from all sides but not hopeless, Smith, at the demand of a group of white clergymen, sang:

I got shoes, you got shoes

All of God’s children got shoes

When I get to heaven, gonna put on my shoes

I’m gonna dance all over God’s heaven

Heaven, heaven

Everybody talkin’ ’bout heaven ain’t going there

Gonna dance all over God’s heaven.

We rendered the spiritual lively and upbeat, as if Smith were putting it on for the clergymen, merriment in the face of subjection. The audience, however, was to understand the thinly veiled critique: Blending judgment and hope, the song affirmed that all God’s children have shoes, but in heaven, some of these children will put them on and dance. More pointedly, the song indicates that talking about God’s heaven isn’t the same as being a part of it. Over and against those who deny shoes while talking about heaven, the lyrics affirm God’s inclusivity, God’s resistance to scarcity, and God’s abundance. The spiritual posits that God’s heaven runs by a different calculus than this world and its dominant religious logic.

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!