“WE'RE NOT HERE to seduce you,” I said.

The laughter signaled that my comment had pushed a boundary but not broken it. When the moderator at my evangelical seminary’s student orientation asked about friendships between men and women on campus, I answered honestly. I wanted to be viewed as a student, not a threat.

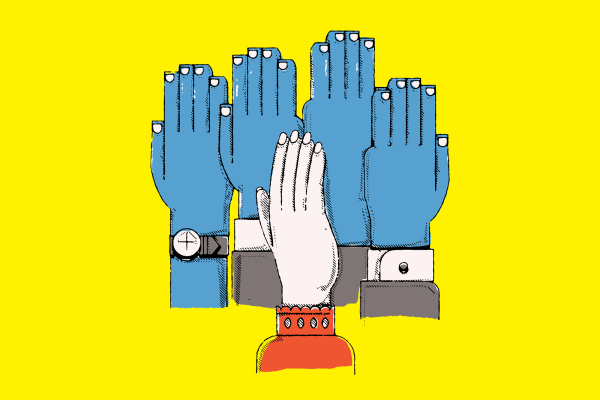

Women seminarians, regardless of where we study, navigate a world not made for us. Many of us study in institutions with long histories of denying our admission, read from syllabi devoid of women scholars, and study under professors who merely tolerate our presence. My own seminary first admitted women as full students in 1975 and into all degree programs in 1986.

Read the Full Article

Already a subscriber? Login