WHEN URBAN CHURCHES disband, congregations face decisions about what to do with their property. In cities with hot real estate markets, church buildings are often sold off and redeveloped as condominiums or for other profitable uses. But the logic of the market need not guide all such decisions.

In 2016, the Community of Christ, a small church in central Washington, D.C., gave away the building it had owned for more than 40 years, a property worth more than $1 million. During the process of disbanding, the church members had decided that they wanted to pass their building on to an organization doing socially meaningful work in the neighborhood. Their story demonstrates ways of thinking about property as a spiritual and collective resource—and how to put those ideals into action.

The Community of Christ was formed in 1965 in Washington’s Dupont Circle neighborhood. Although founded by Lutherans, it was from the beginning an ecumenical church. And like several other congregations forming in D.C. around the same time, the community was an experiment in church: dedicated to social justice and to doing God’s work in the neighborhood, including building relationships with their neighbors. In 1973, the group purchased an 11-room storefront building in the nearby Mt. Pleasant neighborhood, a diverse and relatively affordable area where a number of church members had already moved, and began worshipping in that space. Shortly thereafter, the Community of Christ became a lay-led, shared-leadership congregation, with no single minister and no paid staff. All activities of the church—both spiritual and logistical—were from then on carried out on a volunteer basis by members, and all major decisions were made by consensus.

Part of their spiritual work was to make their building, which was known as “La Casa,” radically open to the neighborhood. La Casa became a place that enabled many people—church members, and also people throughout the neighborhood—to answer a call or fulfill a dream. One church member ran a school for adults with developmental disabilities in La Casa for many years. A toy lending library was housed in the space. A string of small shops operated in the ground-floor storefront rooms, tiny nonprofits rented office space, countless groups held meetings, and benefit concerts raised money for local causes. La Casa hosted the monthly meetings of the neighborhood’s elected advisory commission. It hosted a support group for Latina women who experienced domestic violence, meeting space for day laborer organizers, a fair trade shop, offices for a solar power cooperative, art shows, poetry readings, film screenings, and book talks. For between $10 and $25 a night, nearly anyone could rent the main space, where the church worshipped on Sundays, for a meeting or an event of social benefit.

A community hub

I KNOW ALL this because when I was a toddler in the early 1970s, my family moved to the neighborhood to be part of the Community of Christ. I grew up in La Casa, where I spent nearly every Sunday of my childhood singing hymns during the services and eating donuts from nearby Heller’s Bakery with everyone afterward. When I was older, my band practiced in the building’s basement. I helped put on dozens of punk benefit shows in the space. I worked with others to start a neighborhood radio station that operated out of the building for close to 15 years. La Casa felt like a second home to me—a place I’d lived my most important experiences. And at some point, I became aware that it felt like a second home to scores, perhaps hundreds, of other people too, many or even most of whom I did not know. It was a neighborhood commons: a place that many different people managed to use in many different ways, a wide variety of projects and dreams crisscrossing through the space over time. Sometimes it felt as if half the neighborhood had a key to the building.

But in 2015, 50 years after its founding, the Community of Christ discerned that it was time to end the ministry and formal life together. Its membership, never large, was dwindling. A few key old-timers had moved away, and a few others had died. After months of discussion, prayer, and reflection, members came to the decision to formally dissolve the church. The next question was what to do with La Casa. The congregation did what they had always done when they needed to figure out a problem: They formed a committee. The six church members called themselves the Future of La Casa Committee, and their mission was to work by consensus to arrive at a recommendation of what to do with the building.

At the outset, the committee decided that they would like to give the building to a local group that could pay off the small remaining mortgage and make good use of the space into the future. The congregation as a whole agreed upon a set of four principles regarding their future vision for La Casa. First, the new owner should be a strong, stable church or other nonprofit with the financial and managerial capacity and long-term commitment to utilize and operate the building effectively for good. Second, the building should continue to be available for use by the community at large after the transfer of ownership. Third, the current tenants should have the right to stay for an agreed-upon period of time after the building was transferred to new owners. Finally, the Community of Christ should have the right to continue to use the building for limited purposes for as long as needed.

The committee spent quite some time discussing the second principle. This, they recognized, was an unusual request: One of the key rights of private property ownership is the ability to exclude others from your property. Yet it was because the church had kept La Casa open to so many people and groups over the decades that it had become such a vital center for all kinds of community. They wanted to see this spirit of openness continue under the next owners. Ultimately, they decided not to write this requirement into the covenant on the building, in part because it would be nearly impossible to enforce. Instead, they strove to select a new owner that would be committed to seeing the building as something of a collective resource. This was particularly important given the lack of affordable space for meetings and community events in an increasingly high-rent neighborhood.

The church knew that they were in the strange position of trying to figure out how to give away a valuable piece of real estate in the midst of a hyper-gentrifying city, where affordable space was at a premium. A 2019 study concluded that Washington, D.C., had the highest “intensity” gentrification of any city in the U.S.—and gentrification had been underway in the city, and in the Mt. Pleasant neighborhood, for years.

How do you thoughtfully transfer a piece of property that holds so much meaning to so many people in the context of such pressure? How do you avoid a feeding frenzy of groups desperate for affordable space? The committee did not want to do anything that might ratchet up competition among the potentially interested groups. So they agreed to keep their internal discussions fully confidential. And, though they would operate using a consensus model, they wanted to get it done in a timely manner: They began their work in 2015, with the goal of formally transferring ownership before the end of 2016. If they could not identify a new owner that fit their four main principles, the backup plan was to sell the building at fair market value, without any preconditions, to a nonprofit or a progressive for-profit company—but they were hopeful they would not have to go this route.

With their guiding principles established, the committee was ready to move forward. First, in fall 2015, they reached out to the Metro D.C. Synod of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America (ELCA), with which the Community of Christ was affiliated. The synod staff worked with the committee to see if any local ELCA congregations were interested in taking ownership of La Casa for church ministries. Over five months of exploratory meetings, it became clear that the three local ELCA congregations did not have the desire or the capacity to utilize La Casa.

The committee then created a formal Notice of Invitation for Proposals (NIP) for other potentially interested groups. In April 2016, they sent the notice to about 20 groups with which the church had a longstanding relationship—including the building’s current tenants, groups that had used the building over the years, and organizations to which the church had historically given benevolences. They also created a way for other groups to submit a letter of interest and then be approved to submit a proposal.

A committee-hosted information session later in April for the groups that received the NIP drew much interest—about 30 or 40 people attended. Ultimately, only six groups submitted proposals. The committee created an online tool to review them, and then met over two days to evaluate the proposals together. They requested additional information from three applicants, and then met with applicants to get a better sense of how they planned to use the building. The committee wrestled with their final decision. In a July 2016 report to the full church, they noted that all six proposals were strong, the decision making was difficult, and at various times throughout the process all six organizations had the equal potential to be chosen.

Passing on the gift

ULTIMATELY, THE COMMITTEE decided to recommend that the Community of Christ transfer La Casa to La Clínica del Pueblo, an organization based nearby in the Columbia Heights neighborhood. La Clínica was founded in 1983 to provide health care to the rapidly growing Latino immigrant community. More recently it had been ramping up its organizing and health education efforts among immigrants and was proposing to use La Casa as the base for this work. The church had long supported La Clínica’s mission, and the committee thought they would be good stewards of the building.

The Community of Christ accepted the committee’s recommendation, and in July 2016, La Clínica was notified that it had been selected. There was a joyful coincidence here, embodied in the person of Sally Hanlon. Hanlon was a longstanding member of the Community of Christ, a former nun who dedicated her life to doing God’s work in the world, much of which involved bearing witness to atrocities in Central America. She had also volunteered as an interpreter at La Clínica del Pueblo for years. Though this connection did not impact the committee’s decision to choose La Clínica, that relationship did feel like an affirmation.

On Dec. 10, 2016, the Community of Christ formally transferred ownership of La Casa to La Clínica del Pueblo in a bilingual ceremony inside La Casa. Dec. 10 is International Human Rights Day, a fitting time to make the gift to a group dedicated to organizing for the health and human rights of people often forced to the margins of society. The place was packed. Representatives from the Community of Christ and La Clínica del Pueblo spoke movingly of their hopes for La Casa’s future. Women from La Clínica’s domestic violence support group shared their plans for using the space. We all sang. There were tears of joy and gratitude, and also some of sorrow and loss. Afterward, we shared a meal, in La Clínica’s tradition of a desayuno ecumenical, or ecumenical breakfast, a multifaith meal designed to foster community. We lingered in the building’s central common space, chatting. And finally, it was complete.

New dreams and visions

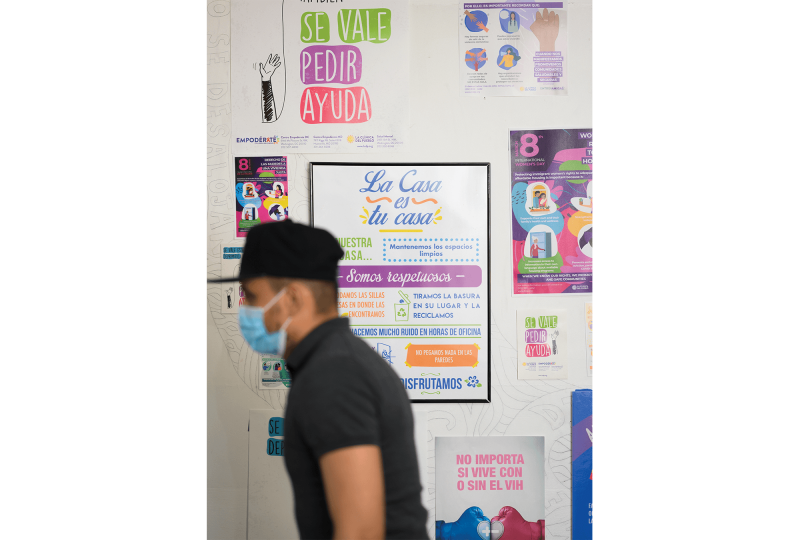

THREE YEARS LATER, I visited La Casa to talk with La Clínica del Pueblo staff about how they were using the space. The building was buzzing with activity. People chatted and hung out in the welcoming open office of La Clínica’s support group for LGBTQ Latinos. Several adjoining tiny rooms enabled private counseling sessions. Women were at work in the office space for the domestic violence support group. La Clínica’s health promoters, who were based in La Casa but did most of their work in the surrounding community, came and went. Young people were gathered in the office of a language-access organizing group that had rented space in La Casa for years and had remained as tenants when La Clínica took ownership.

La Casa, staff told me, was a place for people to feel safe, to feel at home. The gift of the building, they said, had inspired them to make creative use of the space. They took seriously the commitment to keeping the building open for the broader community: Hanging in the entrance way was a framed declaration of their intent to maintain the space as a community resource. They have many plans for the future, including turning an outdoor area behind La Casa into a patio for socializing and using the building as an incubator space for new community projects. Undergirding all this work is the principle that health is about more than going to the doctor: Health is also mental, emotional, and spiritual and is best advanced through a holistic approach that encourages community connection.

huron4.png

The process of giving away La Casa was both highly logical and deeply mystical. It was based in a set of clearly stated principles; it was organized, with a clear timetable; and the Future of La Casa committee made every effort to be fair and confidential. And the process was fundamentally rooted in a spiritual vision: The committee began and ended their meetings with prayer, asking for God’s guidance, and they paid close attention to how the Spirit moved through their discussions. Importantly, this all was undertaken by people who had worked, worshipped, and communed together for decades: They trusted each other, they trusted the process, and they sought input from the wider church community at key points.

The vision underlying the decision to use the building to advance social justice, not for profit, was rooted in how church members had long understood their ministry in their neighborhood and the city. As one committee member wrote, “It was almost in our dying that we became even more clear about the ‘why’ behind our spiritual life together and our desire for our ministries to live on in some core way in ... the Mt. Pleasant neighborhood and D.C.” The spirit of a church that was founded as a place-based ministry continues to reverberate even after it has been formally dissolved.

What the Community of Christ did with La Casa may not work for all churches that are closing their doors. But it may be a guide for some: a way to think about property that can help others answer a call and pursue a dream.

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!