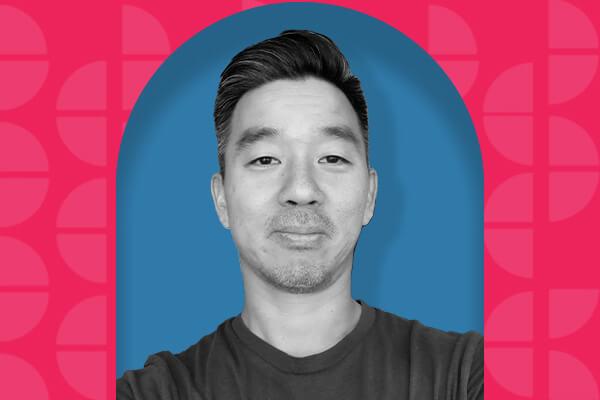

In the July issue of Sojourners, Peter Chin of Rainier Avenue Church in Seattle discusses why so many pastors are stepping away from ministry in the wake of the pandemic, and how this phenomenon could fundamentally change the landscape of the American Christian faith. Editorial assistant Liz Bierly spoke with Chin about the current pressures on pastors, God’s loving-kindness, and how we courageously move forward. Read Chin’s full feature, “Here Is the Church, Here Is the Steeple – Where Is the Pastor?” in the July issue.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Liz Bierly, Sojourners: What drew you to pastoral ministry?

Peter Chin: I think pastoral ministry was definitely a call out of the blue. I had been preparing for medical school all throughout my adolescence and was taking the MCAT and doing all the pre-med requirements, and then just felt a very stark and sudden calling to ministry, which was very unexpected for me and for my family. But it did feel like a calling, and it remains that way. I don’t often feel fitted for it, to be honest, but I do feel like it’s a calling that I’m continuing to be faithful to.

Read the Full Article