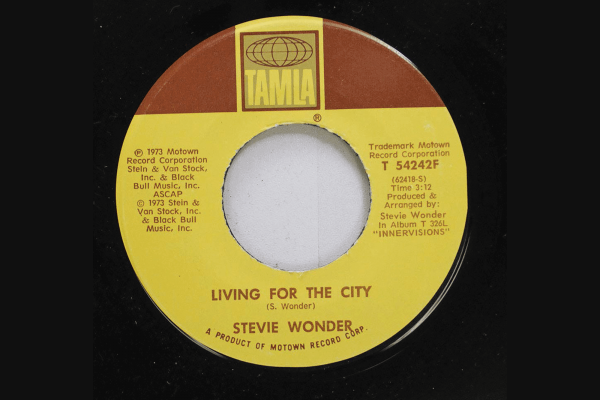

THE OPENING IS spare, just electric piano over a gently throbbing synth bass line, and then the vocal: “A boy is born in hard time Mississippi / surrounded by four walls that ain’t so pretty.” The radio cut of Stevie Wonder’s 1973 hit song “Living for the City” is a four-verse sketch of a loving Black family who work hard, live right, and yet can’t get ahead under the racist economic and social strictures of their Southern town. The instrumentation builds quickly—drums, synthesizer, hand claps, backup vocals—all performed by Wonder. It fades out on a choir of Wonders, singing variations of the chorus: “Living just enough, just enough for the city.”

The album version, more than 7 minutes long, segues from that repeated chorus into a spoken interlude. The boy of the first verse is now a young man arriving in New York City. He is quickly arrested for unwittingly taking a handoff of something illegal and incarcerated for 10 years. The melody and vocals return, heavier, rougher, with Wonder singing from “inside my voice of sorrow” to describe a now broken man who wanders the city, homeless.

“Living for the City” is from the album Innervisions, the third of an astonishing run of five albums Wonder released between 1972 and 1976. During this period, Wonder, a self-taught multi-instrumentalist who made his recording debut in 1962 as a 12-year-old, was stretching lyrically, innovating musically, and embracing a deeper social consciousness.

I first heard “Living for the City” when I was 7, probably from a car radio or a transistor radio blasting CKLW, a top-40 AM station in Windsor, Ontario, just across from Detroit, 90-some miles from my rural Ohio home. CKLW had Motown and other R&B and soul in heavy rotation, in part because of its proximity to Detroit and in part due to hit-spotter Rosalie Trombley, the station’s white music director from 1968 to 1984, who intentionally chose music that would appeal to both white and Black listeners.

“Living for the City”—along with Marvin Gaye’s “What’s Going On,” the Staple Singers’ “I’ll Take You There,” Sly and the Family Stone’s “Everyday People,” and more—were key parts of my moral formation. When I heard “Living for the City” as a child, I thought: This isn’t fair. As an adult, I note the references to both Southern- and Northern-style structural racism, the nascent war on drugs, mass incarceration, and homelessness, forces that have only grown more deadly in the decades since the song’s release.

Maybe “moral formation” is a lofty term to put on a pop song, even one that could fairly be called a masterpiece. But my childhood exposure to church was limited, while pop songs and books were ubiquitous, offering glimpses of experiences, thoughts, and sonic pleasure far from the psychological and social limitations of rural life. They made me want to meet and live among people different from me, to question the status quo and interrogate biases. I wish I knew why a song doesn’t do that for everyone.

CKLW has long since become a news/talk station. And most of us now find music via the internet, the source of so many beautiful and mediocre and utterly destructive things. But “Living for the City” still mesmerizes me. Wonder’s plea in the final verse that his song “motivates you to make a better tomorrow” still resonates. As does, sadly, the final warning: “If we don’t change, the world will soon be over.”

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!