MY DAD HAD a very mixed relationship with America. Based in his experience of and feelings concerning white supremacy in America, I was never sure he loved America and knew with certainty that he hesitated to call it “home.” America was never holy ground for him.

On Jan. 6, 2021, while I was watching the Capitol insurrection on TV, he died in his hospice bed. My screen view of the Capitol mob’s recitation of “hang Mike Pence,” in rhythmic incantation to bring forth the blood-boiling hate, was reminiscent of the ritualistic lynching of thousands from 1870 to 1940, particularly and almost exclusively African Americans.

I also had a screen view of my dad. Given the threat posed by COVID-19 exposure upon his chemotherapy-treated and compromised immune system, we were not able to visit him as we would have liked. My sister had installed a camera system to get a visual. I noticed that he was not moving. I earnestly studied his lack of motion and noticed that his mouth was wide open. This was the death posture. I instantly knew he was gone.

Trying to come to grips with the death of my father, while staring with glazed-over eyes at the Capitol riot, I said to myself: “The insurrection took my dad out of here. He had enough of white supremacy in America.” During the chaos of the insurgency, my dad became an ancestor. In the stark reality of his death, I realized he had been in search of holy ground for a long time.

Separation from the land

MY DAD WAS one of those who moved north from Mississippi in the Great Migration looking for love from his country. As his eldest, his story of migration impacted and affected me at the deepest level of my being. In 1959, without any idea of the odds against him in the North, my dad went to Chicago to make a better life and send for his family — his wife and three small children.

Many publications have lauded the Great Migration based upon what was gained. I am also aware of the other side of the coin, such as profound losses. As a child of a migrant family, I am struck by the loss of deep and weighty family history, traditions, and connections. We saw grandparents, aunts, uncles, and cousins only on occasion, mainly in the summers when school was out, and we traveled South. We were cost-conscious, and therefore only brief, long-distance phone calls were allowed, as well as inconsistent letters, and Christmas gifts that annually arrived in the mail. One loss that I regret the most is separation from the land.

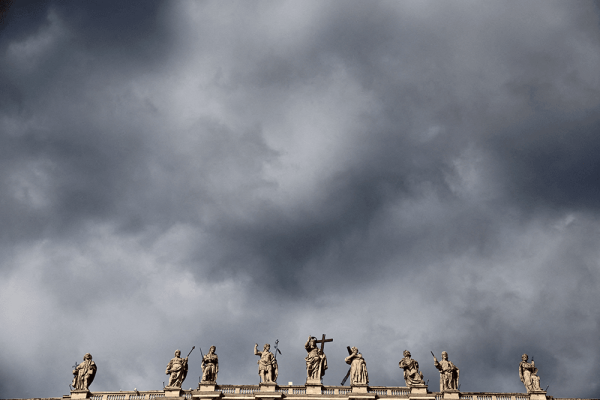

Amid laws blocking land ownership by Black people and the terrorism of land grabs from African American individuals and towns, some Black people were able to accumulate land in the South. Whether or not they owned it, Black men and women always were able to find spiritual and ancestral resources from the land. In a sense quite different from land as capital, their physical labor integrated them and made them one with the soil, and they made it their own. Many never directly profited from their labor, in the capitalist sense, most being required to be slaves, sharecroppers, tenants, forced and seasonal labor. The land recognized no such human distinctions as these and yielded forth its crops. In return, their language, food, families, religion, music, art, and culture drew strength from this spiritual connection with the soil. The land was holy ground.

thomasholyground1.jpg

Between 1900 and 1970, 6 million Black men and women fled southern states. By 1960, three-quarters of the Black population in the U.S. resided in cities. Nearly 96 percent of Black northerners and 90 percent of Black westerners lived in cities. Black people came to be identified with the urban life.

Despite the racial violence that also existed in Chicago, my mom and dad bought a home. I noticed at an early age that white parents would bring all their children in when my mother would put us out to play. And while I did not know how to feel, I could feel the anger in my mother’s face and voice. When I could finally voice my feelings, I said to her, “What is wrong with us that people move out rather than live with us?” I saw her rage in my question, and now I know my parents did everything they could to snatch the inklings of inferiority out of my mental sky. The next Christmas, my mom found a white Santa, painted it black, and put it out in front of the house. Santa would light up at night so that the brown skin could be seen, clearly and defiantly, around the clock. It was probably for us as much as for the neighbors, such that we would know nothing was wrong with us — Santa was made in our image. My family home was set in the context of feelings of anger and defiance regarding the white supremacy of my neighborhood and nation of birth. I learned early on to question if America was “home” — that is, if America was holy ground.

The carnival of white supremacy

AS I WATCHED the siege of the U.S. Capitol, old and embedded memory and feelings came screaming to the surface — ghosts of white supremacy and white mob violence opposing racial equality. I remembered our family of five — my mom, dad, brother, sister, and me — riding back to Mississippi to visit our grandparents and relatives. You could see the Mississippi heat in waves rising off the four-lane highway. Suddenly, there was a man in a white robe and hood with red insignia standing by the road holding paper leaflets. I am not sure of my age and not sure how I knew the robe signified the Ku Klux Klan, but there was a silence in the car. My parents drove past him in eerie silence. My parents never said a word, yet we knew how to behave. Keep quiet and hope not to be noticed, for fear of our lives.

Back watching the insurrection, I turned the sound off and watched the events at the Capitol. In the pictures and the silence, my body felt all the emotions, as if I were in the car riding past the Klansmen in Mississippi — the insurrection — the carnival of white supremacy on full display.

White supremacy chooses to believe lies of white superiority, resulting in historical and structural racism and discrimination. Why would I want to live with this level of mass delusion and denial of truth, particularly when it is so harmful to me and my community? Given all of this, I do not know what concepts such as “America as home” or “love of America” mean. Clearly, I inherited my dad’s search for holy ground.

I think of Robert Johnson’s “Sweet Home Chicago.” Much is made of the myth and truth of violence in Chicago. I feel emotionally, physically, and psychologically safer in Chicago than I do in the ignorance of several other racially insensitive U.S. cities and states. Make no mistake, Chicago has massive white supremacy as well — though I will say that if I could love any place in America, it would be Chicago.

South Side of Chicago as holy ground

BETWEEN THE STIMULI of the outside environment and the response of the human organism is a space open and available to every human being — the freedom to respond. And contained within this space of freedom are inner “reservoirs of life to draw upon, of which we do not dream,” as psychologist William James put it.

These interior reservoirs are where God abides; they are deep wells that are the source of my tears and laughter. It is where inexhaustible digital video archives are stored of all the experiences that have ever happened to me, and how I felt and interpreted them. These reservoirs are the place of the voice and memory of ageless ancestors, their fears and tears, their joys and sorrows, their truth and teaching. When the outside world does not provide sacred ground, there is always the holiness of inner reservoirs.

In this sacred space, stimuli and life can only be experienced, that is, felt — and from the feelings of experience, we then shape thoughts, emotions, and the stories that become the narratives of our lives. The process formation of the narrative self operates like this: We experience sensations in our body, a key component of our inner reservoir, and we label and interpret those sensations with a thought-word such as love, pain, happiness, sorrow, anger, grief, or joy. These thoughts have emotions connected to them, and we form the many thoughts and emotions into a story that we tell ourselves. Many stories combine to form the drama of our narrative self.

As strange as it may seem, given the endemic white supremacy in America, I am aware of bodily sensations that I label as “love” when I think of Chicago. The words of teacher and mystic Elaine Prevallet make sense: “[I]n some places, the particular form into which earth has shaped itself makes of it a kind of soul-landscape, a landscape that resonates with [archetypal] images lodged deep within our psyches.” She believes there are places on earth where “the way the rocks are shaped, or the way the water falls, or the elevations of sky, mountain, and land evoke a mood or feeling in our unconscious, preconscious, and subliminal souls.” These places awaken within us “ageless memory” with a resonance that suddenly engages and attracts us. She says: “When that resonance reaches a certain pitch or intensity, a certain level of intensity, a door or passageway opens within us ... and we call the land holy.” These landscapes of the soul cause our bodies to vibrate at such a unique pitch that we define the experience with the thought-word “holy.”

‘Alit with fire, but not consumed’

THE ORIGINS AND depths of the thought-word holy have to do with a kind of “otherness,” meaning that which is special, not common to everyday use, set apart, unusual, and therefore sacred. Holy has connotation with the Latin word integer, where we get our word “integrity,” which means “whole,” that is, having no broken parts or being of full consistency, uncontaminated, pure, no divisions, fracture, or alloy. Whenever holiness comes in contact with the mundane, normal, common, and expected, then radical encounter results. Holiness touches our ordinary fractured human reality and the experience of that encounter transforms our “inner reservoir of life.”

An example would be the inspiration of a landscape of the soul from the Hebrew Bible in Exodus 3. The holy presence of God was represented in a bush that burned, alit with fire, but not consumed. This unconsumed burning bush caused Moses’ body to vibrate at such a pitch that Moses heard the voice of God tell him to take off his shoes because he was standing on holy ground. Chicago is holy ground because it vibrates within me at a certain pitch and inspires me to take my shoes off.

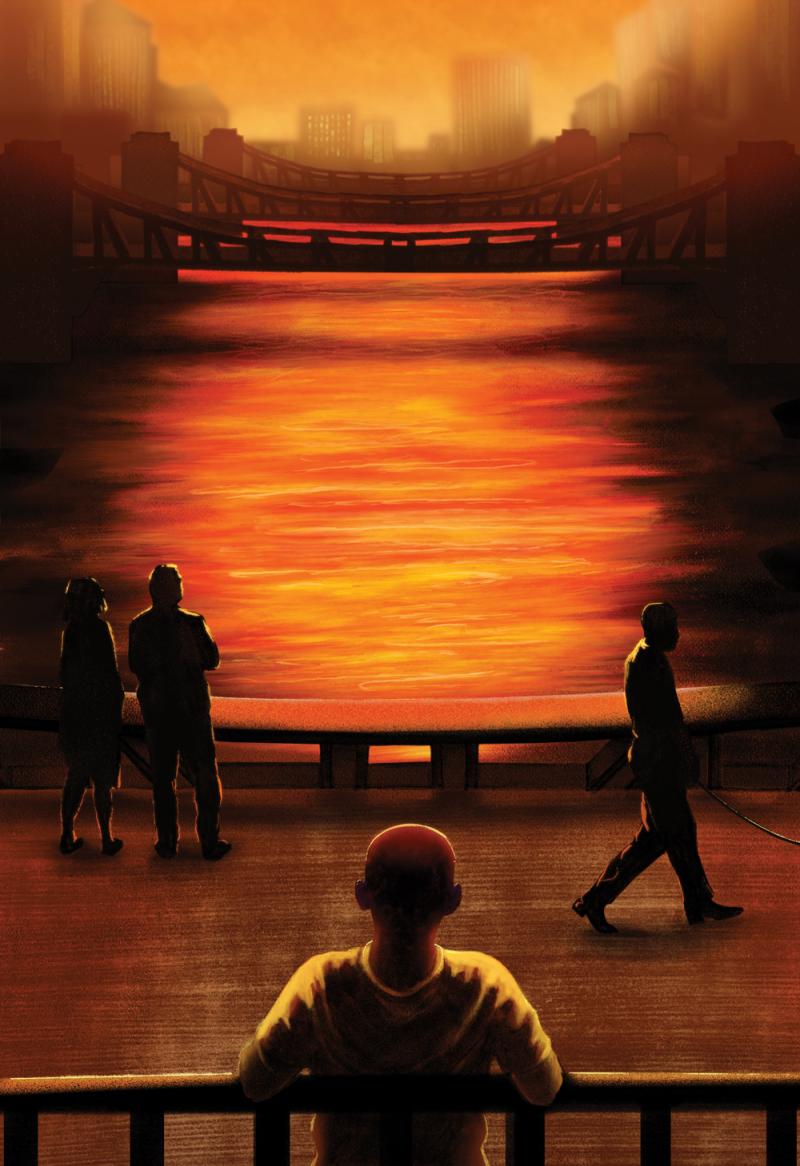

thomasholyground2.jpg

For years, I walked this holy ground, particularly on the South Side of Lake Shore Drive at East 55th Street, where the vibration of the water, land, and beauty of the Chicago skyline helped me make so many of the major decisions of my life. I decided to propose marriage walking that ground. The ground was holy and that was where I felt the call to leave a lucrative corporate position, much to my dad’s chagrin, and engage theological education to become a pastor. After our first daughter lived nine hours and died, my wife and I walked that ground and prayerfully mustered up the courage over several months to try again, and subsequently received our second daughter — welcoming the second and still so desperately missing the first.

When we moved away from Chicago, that same ground was still holy, and in one of the most difficult trials in our lives, we drove eight hours just to get back to that holy ground. We walked, talked, and cried together trying to accept and make sense of awful tragedies that had befallen us. The vibration in our bodies allowed us to hear God and receive clarity, insight, and wisdom — the inner freedom of the choice to respond. And in the times that we did not find direction, we found comfort and discovered that comfort is, in fact, a direction.

The clarity of holy ground

WHEN MY FATHER died, as soon as I could, I made my way to holy ground on the South Side of Chicago. On that holy ground, I began to come to grips with the fact of how much he was my hero, and how I had thought somewhere deep inside that he would never die. Once I accepted his death, the view of my own death became easier, and I gave instruction to my son, daughter, and wife from my clarity: “When I become an ancestor, take my ashes to 55th and Lake Shore Drive. Be sure to point north, and cast them to the waters of the earth, the holy ground from whence I have come.”

I heard a person once say that one of the definitions of holy is the place where one finds clarity. Clarity is the space where my body vibrates in such a way that I can experience freedom of choice regardless of external circumstances. The unparalleled beauty of holy ground is clarity. The clarity I found was that there can be no prospect of psychological, physical, and spiritual health in white supremacist America without settling the question of what it means for me as a Black person to love America, if that’s possible. The answers lie in my daddy’s blues.

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!