UPON READING THE news that the U.S. deported hundreds of migrants to El Salvador, I felt ill. Neri José Alvarado Borges had studied psychology and worked in a bakery. Luis Carlos José Marcano Silva is a barber with the face of Jesus tattooed on his stomach. As the daughter of an immigrant, I wept, thinking of their fear and families’ grief. In the face of a government that thrives on cruelty, we need resources that help us preserve our human capacities for hope, courage, and compassion.

Recently, I’ve found comfort in paintings from books of hours, a form of prayer book popularized in Europe in the 1200s to make contemplation simpler for the laity. These paintings, known as “illuminations,” are distinctive and, according to the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Wendy Alpern Stein, include “some of the greatest paintings and drawings of the late Middle Ages and early Renaissance.”

Once the most published texts of their time, books of hours were often bespoke, commissioned by monarchs and aristocrats and crafted by luminary artists of the day. Each unique book of hours contains a liturgical calendar, gospel excerpts and psalms, and “The Hours of the Virgin,” which Stein calls “the heart” of the form, “a series of prayers and praise for the Virgin Mary [recited] at the eight canonical hours.” The books were made and written by hand. The illuminations include beautiful borders, often of botanical elements like ivy or flowers that decorate the edges of each page. Passages of text begin with an ornately decorated and framed capital letter. And the illustrations that complement the prayers and readings are drawn with vibrant colors and metals like gold and silver.

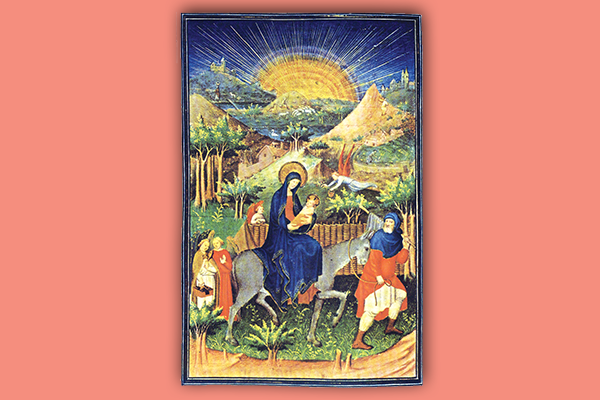

Curator John P. Harthan, in his survey anthology The Book of Hours, introduced me to my favorite illumination: “Flight into Egypt” by the Boucicaut Master. Included in the early 15th-century book The Hours of Marshal Jean de Boucicaut, “Flight into Egypt” depicts the gospel story of Joseph, Mary, and Jesus fleeing Herod. Though the artist is anonymous, they are now praised, in Harthan’s words, as a “landscape artist of genius who achieved effects of light and aerial perspective [never before seen] in book illumination.” In “Flight into Egypt,” light radiates from the earth and the scene glistens with rich shades of red, blue, green, and gold. Four angels appear: two follow from behind with supplies, one scatters blessings from above, and one watches carefully from afar.

We know the holy family was a refugee family, and we know Christlike love dissolves borders and demands generosity. In moments of terror, no matter how corrupt and cruel the government may be, God is with the vulnerable.

Stein calls illuminations “painted prayers.” Too often, we think of prayer narrowly, as words spoken or thought — a plea, a question, thanksgiving. But if I were to paint a prayer for the migrant detainees, I would place small angels around them, blessing them, watching over them, traveling with them. I would draw the sun shining brightly on the horizon with hope for a just future. Imagine if we could see like this illumination: not just the horror, but also the presence of God. We would feel consoled but also emboldened, remembering that God is found in tenderness.

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!