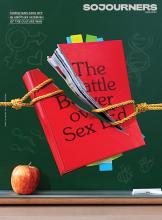

In the June issue of Sojourners, freelance journalist Bekah McNeel reports on the ongoing battle over sex education in schools—and the role of Christians on both sides of the skirmish. While some Christians are leading the culture-war fight, McNeel highlights that there are others who are working for a comprehensive approach that goes beyond silence or shame. Editorial assistant Liz Bierly spoke with McNeel about her reporting process, her upcoming book, and what is keeping her hopeful. Read McNeel's story, “The Battle Over Sex Ed."

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Liz Bierly, Sojourners: I imagine there are times, especially with the topics you are covering (equity, race, abortion, education) where you talk to someone and all of a sudden, you’re like, “Wow, this story is not what I thought it was.”

Bekah McNeel: So often. And those are my favorite stories. I love working with editors who I can call and be like, “Hey, this is bigger than we thought,” or “There’s a nuance here that we really want to highlight.” Especially as you earn trust with a source, a lot of times in the first conversation or the beginning of a conversation, they’re rightfully suspicious of you. If they tell you a piece of their truth and you’re like, “Anyway but back to what I want to talk about,” they’re going to be like, "Alright, you’re not interested.”

But if you have an open hand with the story, people will take you—sources will take you—to a place that the narrative and the discourse hasn’t gone yet. And that’s what I love. I’m a professional journalist—if the editor says stick to the plan, we stick to the plan. But I think the better stories are when we don’t.

Read the Full Article