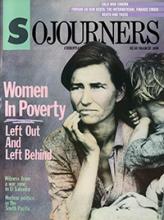

That women are poor is nothing new; that women are poor is nothing unusual. Women have been exploited as property to be bought and sold, as goods to be bargained and bartered, since biblical times. Women have been forced to depend upon men for their economic survival in primitive, feudal, industrial, capitalist, socialist, communist, and even our most "advanced" societies. Women have been oppressed, and even their very nature has been maligned, by Christianity, Judaism, Islam, Buddhism, Hinduism, and other religions. Economic, political, professional, and sexual discrimination have been experienced by women of every race, class, and culture.

Women have always been disproportionately poor, and many women have been poor their entire lives. But many of the social movements of the past 20 years, particularly the women's movement, have attempted to redress the social and economic inequalities suffered by women throughout history. Yet for all our "progress," for all the gains made in women's rights, there is still not only a large number of poor women in the United States--and throughout the world--but now there are more poor women than ever, and they are getting poorer.

Two out of every three poor adults in this country are women. And a 1981 study by the National Advisory Council on Economic Opportunity, to stress its point about the rapidly growing impoverishment of women, concluded that if the current trend were to continue "to increase at the same rate as it did from 1967 to 1978, the poverty population would be composed solely of women and their children before the year 2000." It is the frightening picture painted by these sobering statistics that social scientists and feminists have labeled the "feminization of poverty."

Forty-six-year-old Nona, like many black women from the South, wears poverty like a birthright:

Read the Full Article